Some comments on my charts showing the results of national forest non-management have contended that I’ve placed too much emphasis on reduced tangible and material outputs (renewable energy, wood and paper products) and on adverse economic and social impacts (jobs lost, stressed families,

communities and local governments) . Critics claimed that the non-material results of “hands off” management were being ignored.

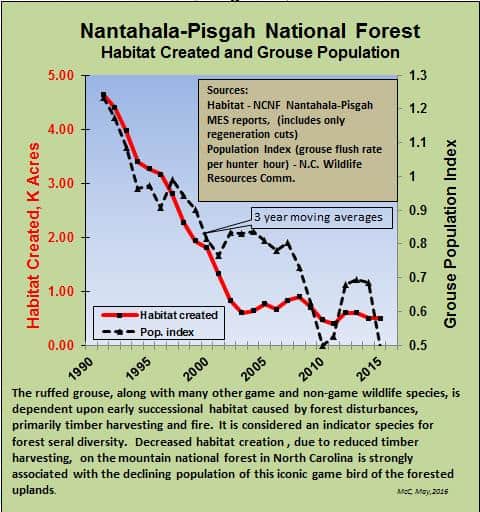

In an attempt to remedy this imbalance I offer the following .The ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) is widely used by wildlife biologists, both in the eastern and western U.S., as an indicator species for assessing the status of wildlife habitat and the ecological diversity of upland forests. The chart demonstrates the effect of virtual non-management of the timber resource on this key species in the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest,(N-P), the mountain national forest in North Carolina. According to the N.C.Wildlife Resources Commission 2015 annual report, “By all measures, grouse hunting during the 2014-15 season was the poorest on record”.

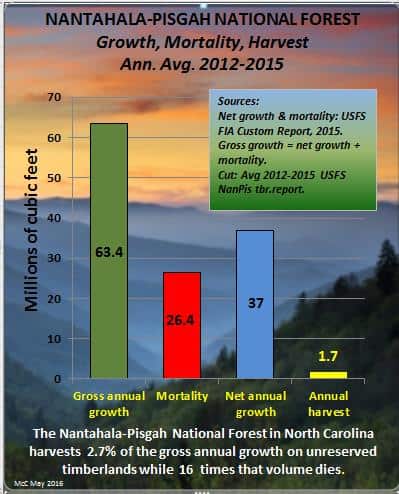

The U.S. Forest Service is currently creating about 500 acres per year of early successional habitat through regeneration cuts (clearcut, shelterwood, and group selection). This comprises about .06% of the 908,700 acres of unreserved timberland found on the forest. An additional + 100 acres is thinned annually with varying beneficial impacts on ground cover. The acreage of prescribed burn has increased steadily since 1995 and now averages about 10,000 acres annually. While this treatment promotes the development of early successional habitat, its aggregate impact is difficult to assess as effects vary widely with fire intensity, ambient temperature, stand density, season of year, timber type, and ground cover.

Good quality early successional habitat can best be produced by well-designed regeneration harvests. Current management of the N-P produces about 500 acres annually of this habitat. Maintenance of suitable grouse habitat and the age class diversity essential to forest health requires, at a minimum, treatment of ~.5 % (about 4500 acres for the N-P) of the forested area annually. While the report focuses on grouse, be aware that the decline of early succession habitat is adversely affecting not only grouse, but of other game and non-game species such as woodcock, white-tailed deer, wild turkey, golden-winged, prairie, and cerulean warblers, Bewick’s wren, yellow-breasted chat and a host of others (See Hunter et al, Wildlife Society Bulletin 29(2) 440-445)

The summer 2001 edition of the Wildlife Society Bulletin, a peer-reviewed journal of the professional organization of American wildlife biologists, contained a series of 8 articles. These examined in depth the changes in habitat and wildlife populations that are resulting from current non-management of wildlands in the eastern United States. The authors reached the unanimous conclusion that, considering both game and non-game species, more intensive management is urgently needed and that the continuation of the current “hands-off” policies would result in “the loss of some of the most interesting and diverse natural communities in eastern North America”. The habitat-population chart suggests that this prognosis is becoming a reality.

It should be noted that the Nantahala-Pisgah N.F. has 105,000 acres of Wilderness and Wilderness Study areas and the neighboring Great Smoky Mountain National Park has 522,000 acres of forest land on which timber harvesting is prohibited.

Mac McConnell

May, 2016

If one defines forest health according to the population of a game species dependent on one particular successional stage, then it would seem that forests need to be managed.

But is that how forests should be managed — as game farms? Sometimes they will. It’s a good discussion to have. But hunting is just one lens through which to see nature.

^ Like ^

Thanks, Matt. Though looking at what I wrote, I owe an apology — Mac didn’t just talk about the game species, but other early-successional species too.

That said … I’m still uncomfortable when an argument starts off with game species, with the others as secondary. It feels like the forest is being seen through that one-dimensional game-producing lens.

There are also other ways to foster post-disturbance habitats than harvesting wood. What about promoting beaver, which create both disturbance *and* wetlands? I don’t know Nantahala-Pisgah, but if I was worried about a shortage of disturbance habitats there, the first thing I’d do is find numbers on how many beavers are trapped there. There’s also (says a quick Googling) a utility corridor(s) going through the forest; those need to be kept free of mature trees, and elsewhere are being actively managed as permanent early-successional habitat.

Not that harvesting is always bad, but it feels like arguments in favor of managing for disurbance always default to cutting without acknowledging other strategies.

The post and commentary thus far seem like textbook examples of the insurmountable ideological divide regarding forest management, where one side will use any excuse to justify timber harvest while the other side will use any excuse to prevent timber harvest.

Speaking to this post specifically, why not manage for game species? Each forest must establish management priorities based on environmental/ecological and socioeconomic needs. If forest users value game species and adverse impacts are minimal/nonexistent, why not make forest users happy?

Regarding the method of providing early successional habitat, if timber harvest is as effective as other methods, shouldn’t forest managers have an obligation to choose the management alternative which provides the most value to the landowners (us)?

Regarding Brandon’s suggestion to consider beavers, my gut tells me most potential beaver habitat lies within reserves. If not, beavers should certainly be considered for a broad range of management objectives.

Insurmountable? Preposterous. Don’t teach algebra and calculus in high school and see what students face in the world of college and beyond. Don’t create a mosaic of distribution and abundance of habitat conditions and deny the existence of roughly 2/3 of the biota that exists in the temperate rain forest of the Southern Appalachians. Don’t teach about the complex relationships of ecological interactions between species and their environment and you get oversimplified opinions that are basically rumors, or myths. The fundamental argument seems to be framed around what tools are used to achieve diversity. You may not like the sight of it in the beginning, but you have to prepare a site to build a house. The end result is the objective. For plants, insects, and animals you have to create a ‘home’ as well. You may not like the sight of it for the first year or two of a ‘timber harvest’ (there are other terms for habitat creation and maintenance), but for decades, even centuries thereafter, it provides habitat for a continuum of resident, migratory, and wintering species from salamanders, to birds, to black bear.

I think kevin makes a great point! As an example here in the Pinelands National Reserve ruffed grouse were common to all woodlands when the reserve was created in 1979– they are now extirpated across this more than one million acres– they were never really hunted much here but are now gone because of the maturation of the forest. it makes no difference if they were viewed as a game bird or just one of the may species found here – they don’t care if they are called a game bird or just a species , they have no say in what they are called! But we an obligation to sustain them on this landscape! Why is a northern pine snake more important than a grouse for if they were extirpated here the govt would call for a moratorium on all land use until they were brought back some magical way! All species remain important and whether we hunt them or not they all need consideration!

As to beaver – here beavers have become responsible for the destruction of a globally threatened forest ecosystem — atlantic white cedar– a forest in steep decline across its range and it cannot withstand the flooding of beavers – cedar swamps provide critical habitat for many rare species !

it isn’t any either or situation – yes we should evaluate natural disturbances and see if that can supply the needed early successional habitats – but when that doesn’t and species become at risk , we should allow for consideration of forest management that may use harvesting as a tool!

But it seems as though we will go round and round with this tit for tat and what ever species make it – so be it!

I think active management needs to be given fair consideration at times!

Walking through our Pinelands and not hearing the flush or drumming of a grouse is sad and irresponsible and that has nothing to do with being able to hunt them!

“Why not manage for game species?” “If forest users value game species and adverse impacts are minimal/nonexistent, why not make forest users happy?”

That’s a fair question. One thing that makes it hard to answer is figuring out who the “forest users” are. I would suggest it is the “forest owners” that should be consulted, but in any case that is what the Nantahala-Pisgah is doing right now as it is revising its forest plan.

The other thing that is important to understand is that the Forest Service does not have unlimited discretion to make this decision. By law (NFMA), and to minimize the adverse impacts, the plan must provide diversity for plant and animal communities. By regulation this means that it must provide “ecological integrity,” which means that important aspects of the Forest’s ecosystem (like early successional habitat) must be “within the range of natural variation.” Basically this means that there should be about as much grouse habitat as there was before we started logging. And I would argue that this should take into account the amount of grouse habitat on private lands in the ecosystem.

One more thing. If there are species at risk because of a shortage of late successional forest (which is more common than for those needing disturbed forest), there may be a need to manage national forest lands to contribute to a viable population within the species’ range. This may mean “overproducing” this habitat on the national forest lands in the species’ range, and underproducing grouse habitat. Maybe the grouse population was being overproduced on the N-P 25 years ago, and current levels are what they should be.

It is interesting how people are the evil source of all the wrongs in the world. However, though they were nearly hunted to extinction, the bison has famously made a recovery. Doug MacCleery in his “American Forests: A History of Resiliency and Recovery” (1994) shows how elk, whitetail deer, pronghorn, and turkey populations have all increased many, many times during the 1900’s. [In fact, the introduced turkeys in my neighborhood have become pests!]

Dr. James Bowyer used to give a quiz to his college students to better understand their understanding of forest issues. A true/false question concerned the idea that forestry has/has not caused the extinction or even the threat of extinction of any wildlife species – it has not. Dr. Patrick Moore, a co-founder and longtime co-leader of Greenpeace eventually came to the same conclusion.

The discussion about beavers is particularly interesting. Some years ago, I went to a joint Washington/Oregon environmental educators conference where a speaker talked about how beavers had been eradicated; most of the audience nodded in agreement. I talked to her later and she seemed genuinely surprised to find that beavers are not only not extinct, they are oftentimes pests because they commonly block culverts under roads and railroads and cause road failures. As we work to “restore” riparian areas, they like to eat our work! There is some thought that, where watersheds have a lot of beaver dams, the sediments in the ponds bury a lot of good spawning gravels. People in town commonly complain about the beavers eating their apple trees! I can assure you, these are not “reserved” forests nor are the farms and those urban apple trees in reserves.

A few years ago, I was on an SAF field trip in the Shenandoah’s of western Virginia. A fellow from the Nat’l Park Service told us about some sort of salamander that needed open, rocky terrain. They were prevented from harvesting to create that habitat just as they were prevented from prescribed burning. Consequently, because trees are rather invasive, the habitat for this particular salamander was declining though the land managers were charged with providing suitable habitat – a real Catch-22.

What a land manager needs is to understand the landowner’s objectives. With that understanding, it is entirely possible to manage a forest to meet the needs of a very diverse flora and fauna. To be sure, everything we do in the forest has positive effects to a certain set of flora and fauna just as it has adverse effects on a different set of flora and fauna. Thus, it is imperative the land manager work with both the botanist and the biologist to meet the needs of both flora and fauna. [While they may make the rules and despite what they may think, there are very few politicians who can truly say they are well versed in either botany or biology.]

I’ve said this before and will say it again – I think public lands could be grown on long rotations, providing both early as well a late seral stages. This should pretty much meet the needs of a very diverse set of both flora and fauna and, not coincidentally, the needs of people, too. This may also mean altering tax laws to encourage private forest landowners to grow their forests to an older stage.

Um, excuse me Dick. Bison have “famously made a recovery?” How many wild, genetically pure bison are there in the U.S. currently? How many where there in 1800? or 1400?

To be sure, there may have been many hundreds of thousands or millions of bison at one time, but, given that they were nearly hunted to extinction and with today’s world of farms, ranches, cities, freeways, etc., that they exist at all is remarkable and that they exist in the numbers they have seems like a pretty good recovery. Returning to the numbers of free-ranging bison of the 1800s or 1400s is simply not a reality in today’s world.

Dick, you understand the difference between wild, genetically pure bison and a herd of beefalo on a farm, right?

Are you saying Yellowstone’s bison and those I saw alongside the highway at sunrise in the Black Hills were actually on a farm? If they were farm-raised, I was badly fooled ‘cuz I’d have sworn they were wild.

No Dick, what I’m saying is that there are only a few thousand genetically pure, wild bison in the U.S….A tiny fraction of a tiny fraction of what there was historically.

When I created the post, using ruffed grouse as an indicator species to measure the impact of lack of early successional habitat on wildlife, I thought to myself “Someone is going to accuse me of advocating managing the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest as a game farm”. And sure enough, that’s what happened (Brandon has graciously retracted that statement and apologized – Thank you Brandon!). I would rather have used the golden-winged warbler but grouse is the species with the hard data so I went it.

Jon Haber makes the pertinent point that management should stay within the “range of natural variation”. This emerging and, to my mind, nebulous concept has not, as yet, been rigorously defined. I’ve never quite accepted the premise that conditions that served well the hunter-gatherer should be the management model for forest lands in a post-industrial society with 7 billion, mostly energy-poor and ill-housed, humans. That aside, the seminal paper “Overview of the Use of Natural Variability Concepts in Managing Ecological Systems” (Cited by 991) (www.geo.oregonstate.edu/…/landres_etal_EcolAppl_99.pdf) is required reading for those who would understand the basics of natural variability. The authors make this statement:

“Management use of natural variability relies on two concepts: that past conditions and processes provide context and guidance for managing ecological systems today, and that disturbance-driven spatial and temporal variability is a vital attribute of nearly all ecological systems.” (Emphasis added)

The following table, taken from An Assessment of the Ecosystems of Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest & Surrounding Lands Josh Kelly 12/17/2013 (https://www.conservationgateway.org/…/SBR_DepartureAnalysis_FinalReport_Kelly……) demonstrates the need for active management to advance the restoration of national forest lands towards the natural range of variation. Note that the omnipresent driver of ecological departure from natural variation is ”Too much closed canopy”.

Table 3: Ecological Departure of Ecosystems in the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest and surrounding lands by ownership.

Ecosystem Natl. For. Other Lands All Lands Drivers of Departure

Dry Oak Forest 84% 80% 80% Too much closed canopy, lacks old-growth

Pine-Oak/Heath 83% 74% 79% Too much closed canopy, too much late-seral

Shortleaf Pine-Oak 83% 63% 71% T Too much closed canopy, too much late-seral, lacks early-seral

Dry Mesic Oak-Hickory 70% 71% 71% Too much closed canopy, lacks old-growth

Mesic Oak-Hickory 70% 74% 72% Too much closed canopy, lacks old-growth

Other scholarly papers emphasize the need for spatial heterogeneity (the complexity and variation of a system property [e.g. plant biomass, cover] in space). This quote from (www.umass.edu/…ecology/…/chapter12_hrv.pdf) makes clear the need for seral diversity.

“Spatial heterogeneity per se is an important component of ecological systems. Reducing

spatial variability typically results in declining biological diversity, increased vulnerability to

insects, pathogens, or other disturbances, and decreased resiliency to subsequent

disturbances”

This desirable landscape quality can best be achieved by directed and controlled treatment (thinning, regeneration cuts), or, in a less predictable way, by prescribed fire.

The Nantahala-Pisgah was also discussed here: https://forestpolicypub.com/2014/07/25/hhashing-out-habitat-crowd-debates-wildlife-habitat-in-forest-management-plan-meeting/

The two main points of my comments on their plan revision process were that they hadn’t identified any wildlife species at risk because of lack of early seral the conditions on the Forest, and that they hadn’t yet suggested how the things that have limited forest management activities are going to change. They are now aiming for a DEIS and draft plan this fall, where we’ll see what they have in mind. Here’s what I said about wildlife:

“The potential species of conservation concern include two that are associated with open areas. While evidence is provided that golden-winged warblers may be at risk, the assessment concludes that, “Since golden-winged warblers are associated with high elevation open habitats, they are conserved through the implementation of current standards in the revised Forest Plan.” Ruffed grouse is also included as a potential species of conservation concern, and its populations are said to have been declining over the last several years, but the assessment does not discuss ruffed grouse at all.

Just catching up on this thread….

Gary mentioned how “for plants, insects, and animals you have to create a ‘home’ as well. You may not like the sight of it for the first year or two of a ‘timber harvest.’” But how does engineered disturbance in the form of logging compare to natural disturbance? Beaver ponds, mixed-severity fires, disease and storm falls seem to produce far richer — i.e., far more structurally complex — post-disturbance habitat than the forestry practices I’ve seen.

(And it’s eminently possible that I just haven’t seen good practices. Would be happy to be corrected.)

Bob mentioned the beavers becoming a threat to endangered Atlantic white cedar swamp forests. While in particular places established forests might not withstand flooding by beavers, it’s my understanding that, looking more broadly across time and space, beaver activity creates conditions in which white cedar forests can grow.

Dick mentioned the bison “recovery.” True, they didn’t go extinct, and that was a tremendous achievement. But if today’s tiny, migration-denied and frequently exploited herds are the definition of recovery … oy. Talk about shifting baselines.

Mac, thanks for the link to that paper — it got truncated in your comment but am looking forward to reading. (Here’s the full link: http://www.umass.edu/landeco/teaching/landscape_ecology/references/Landres_etal_1999.pdf )

It seems fair to say that Nantahala-Pisgah has a preponderance of middle-aged and late-middle-aged forest, and opening the canopy is a goal. But my question is, why then treat disease like it’s an ecological catastrophe? E.g., for N-P see:

http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5411854.pdf

Tree-infesting invertebrates, native and non-native alike, are treated as threats to forest health, yet can’t they produce precisely the canopy-opening and early-succession-promoting effects that we want to engineer?

As for the bison, I’m just happy they still exist and that their numbers have grown! While free-ranging bison would be nice over a very broad landscape, in today’s world of farms, ranches, fences, freeways, cities, etc., it just won’t happen. Instead, we’ll have to manage those wild herds that still exist (Yellowstone NP, for instance) to assure a diverse gene pool. Well-managed “beefalo” herds might even play a role in this just as pandas and condors are raised in captivity with the goal of preserving the species and reintroduction into the wild.

Sure, insects will create “canopy-opening and early-succession-promoting effects”, but, all too often, their populations get out of control and, as we see all across the western US and Canada, they lay waste to many thousands of acres of forest. Forests without fire (either natural or prescribed) and without treatments to mimic fire, become older, denser, less drought-tolerant, and with increased quantities of fuel; all make a forest ripe for insects as well as fire and disease. I’d much rather have these openings and early succession effects by design.

Unfortunately, we see cutting as an invasion of the sanctity of these forest lands. What is generally overlooked are the effects of once natural fires. We vehemently battle these in order to prevent their encroaching upon developed areas. However, we do nothing to balance the variant stages of succession that would naturally occur were we to be truly “hands off”. I’m not advocating the unchecked allowance of wildfires by any stretch, but if we are going to prevent one we are responsible for pursuing the balance we have disturbed.

Are there any large tracts of forest (over 1000 acres) where there has been absolutely ZERO management over the course of the last 200 years? Do we even know what that kind of forest looks like? Have there ever been studies of such areas (if they exist) to see what actually happens in a forest that has zero management with no timber harvest in that kind of time period?

It seems like so many want to put forward an agenda of some kind of “management” for forests (block cutting, selective cutting, controlled burn, timber harvest, etc.) but in all the blogs and newsletters and other articles I’ve read, there never seems to be a completely “hands off” approach which lets any true long-term research happen over a long (60+ years) period of time.

We want quick answers, don’t we? But forests don’t get to “old growth” (by my definition) in a few decades, it takes a century. We’ve changed practices multiple times since the development of national forests and parklands and prior to allowing ANY forest to age by that amount. I’d wager that for science and timber companies and game advocates to truly understand what the long-term outlook for a forest’s health can be, they’d need to have a much more long-term study than the past 20 or 30 or even 40 years. If this isn’t done, then the rest of the figures and studies and data are simply so much guessing and theorizing.

I think Forest Service Experimental Forest and NSF LTR’s were set up to do the long term work. There have been experiments, and in my experience you have to have controls, which are untreated areas. Here’s a link to the Experimental Forests in the Rocky Mountain Research Station area https://www.fs.fed.us/rmrs/experimental-forests-and-ranges. But there are also famous ones like Hubbard Brook in the East, and Bent Creek in the SE “Long-term studies, some established more than 80 years ago, are still yielding valuable information on forest stand development, stand dynamics, and timber growth and yield. Today some of those studies are being used to address current issues such as climate change mitigation through carbon sequestration..”

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/bentcreek/

Of course, what happened in the past is no predictor of the future with climate change, invasive species and so on.