I continue to fine some nuggets of good information in the Missoulian’s big series on the timber industry in Montana, even though none of the Missoulian articles (to date) have bothered to reach out to anyone in the environmental community and get our perspective on the timber industry, public lands management and the reality that we’re pretty much always blamed for all the timber industry’s woes.

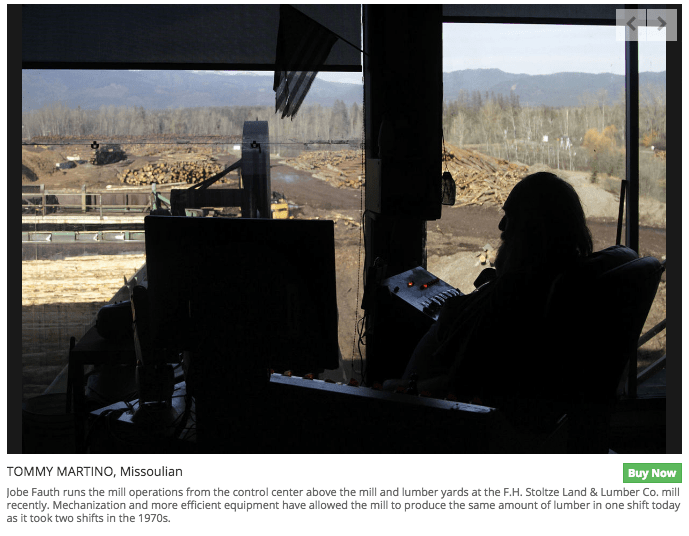

The title of this post is a direct quote from Paul McKenzie, the resource manager for the F.H. Stoltze Land and Lumber Company in Columbia Falls, Montana, and is taken from this article.

Let the substance of that acknowledgement from Stoltze Lumber sink in for a second. Essentially they are admitting that when they mechanized their lumber mills half their employees were let go, but they still produced the same amount of lumber. And yet, despite this fact, the timber industry in Montana still gets away with blaming all the timber industry worker layoffs on environmentalists? How is that even possible?

Previous Missoulian articles documented the Montana timber industry’s “old-growth forest liquidation” strategy, which dominated the scene in Montana from 1970 to 1990. During those two decades corporations like Champion International tripled logging levels on their own lands – most of it via logging of old-growth forests. But other timber mills in Montana also took part in that old-growth logging frenzy of the 70s and 80s.

As the timber industry was pretty much mowing through all their own old-growth, they turned to the U.S. Forest Service and started pressuring the agency (and politicians) to open up vast swaths of public national forest lands – including old-growth forests and roadless areas – to large-scale logging and roadbuilding schemes.

Apparently, if you believe the timber industry lobbyists and mill owners story now, they actually had no idea that what they were during in previous decades was bad for forests, fish, ecosystems or long-term sustainability. Of course, I don’t buy that argument for a minute. And you shouldn’t either.

Historically speaking an interesting comment, but what exactly is the point? I searched in vain for a premise or a conclusion. Here are some facts:

The National Forests in Montana grow 576 MMcf annually. With an Allowable Sell Quantity of 110 MMcf. the forests harvest 26 MMcf annually or 4.6% of the total yearly growth. 510 MMcf dies, twenty times the volume cut . The unmanaged, over-dense, and aging timber stands on these forests are being decimated by fire, insects and disease. Ninety eight percent of the mortality is not harvested, while the forests’ potential to provide jobs and to promote family stability and community vitality remains unrealized.

What does past (or present) harvesting by private owners have to do with these facts? How does timber industry harvesting of trees from its own lands produce the ageing, unhealthy, and over-crowded timber stands now found public land?

Your lead paragraphs on Stoltze Lumber Company at Columbia were especially puzzling. A quarter century of virtual non-management on national forest lands has produced an untended woodland where dead pines and mega-fires are the norm and NF-dependent communities, local governments and schools, workers, and families suffer economic and social disruption. Are you saying that the modernization of the Stoltze mill is responsible for this debacle?

Addendum to my “Reply”. All volume figures are on unreserved timberland and were extracted from the USDA Forest Inventory and Analyses (FIA) data base. Feel free to check.

Well said Mac

That the mill needs half the workforce to produce the same amount of lumber cannot be laid at the feet of the environmental community. However, it is equally true that the environmental community put a good number of mills out of business. [My county, half the size of Rhode Island, lost around a dozen or so small, local, family-owned mills during and since the Clinton era (only 2 still remain with one of those part of a very large nation-wide conglomerate).]

As for the Stoltze mill, it was likely a matter of producing more with less; that means producing with a smaller workforce and keeping labor costs down. Otherwise, they’d have to sell their product at a higher price if they were to stay profitable and stay in business. Given today’s global economy, that simply cannot happen as other regions of the US and, especially, foreign countries will step in with lower prices. This is nothing more than simple economics 101.

The newspaper’s reference to over-cutting during the 20th century requires a history lesson. Prior to World War II, virtually all logging took place on private lands. Then, after the war, we had the Baby Boom and the birth of suburbia. However, the private lands had not regrown to the point they were ready to be harvested again. This meant the consumer had to turn to public lands; industry was merely working to meet the consumer’s demand.

Further, when I was in college, national policy was to convert those old forests as quickly as possible into young, thrifty, fast-growing forests; the old forests were deemed to be dying, decadent, etc. Again, this was national policy though the environmental community likes to lay this at the feet of the timber industry.

I just started reading a book, “The Irresponsible Pursuit of Paradise” (2016) by Dr. Jim L. Bowyer, Professor Emeritus, Univ. of Minnesota. In it he talks of our consumption of resources and our attempts to save the environment. In the preface, he writes: “What this means for the US is that citizens are able to enjoy the benefits of high consumption with minimal exposure to the environmental impacts of that consumption – especially in the case of metals. Moreover, these same consumers are able to bask in a feeling of environmental superiority over raw material supplying nations whose environments are not as pristine as those in the US. It is an ethically bankrupt position”.

He goes on to say that, between 1950 and 2012, the volume of timber in the US increased by over 57 percent even though our population grew by 96 percent. This seeming contradiction is because, even though we’ve put off-limits vast acreages of forest, our net imports of softwood for the past few decades accounted for 23-35 percent of our consumption. Bowyer presents two graphs, one showing national forest timber harvest declined 87 percent between 1985 and 2014 while softwood imports increased 140 percent between 1985 and 2005! Is there a correlation somewhere – it seems likely.

[Because so much of eastern Oregon’s forests are federal, with a lack of logs, at least for a time, some mills were actually “importing” logs from Montana. Transportation costs, of course, were prohibitive and most of those mills no longer exist.]

All this simply goes back to the consumer; if we want wood in our lives, someone will produce it. If we won’t produce it here, then we’ll look to other countries. In the process, we stick our heads in the sand as we pat ourselves on the back when we save our forests but export the costs of our consumption. Bowyer is correct when he says this is “ethically bankrupt”.

The American consumer has to do only one thing if they want to put the forest industry out of business – quit buying wood. That also means finding alternatives to using trees in our toothbrushes, toothpaste, artificial vanilla flavoring, cinnamon, cell phones, rayon cloth, cellophane tape, cellulose sponges, ice cream, medicines, grated parmesan cheese, and a few thousand other consumer goods. Of course that also means the forester would have no reason to plant a tree or to even take care of the forest. Further, the forest landowner would have no reason to keep the land in forest as they’d be ahead to convert the forest to other uses (housing, farms, etc.).

Mac’s comments about Montana’s national forest yearly growth versus harvest parallels Oregon’s story. Oregon’s national forests harvest 7 percent of its yearly growth while losing 29 percent to mortality (i.e., feed bugs, disease, drought, fire, etc.). The remaining 64 percent is added to the forest as live, green, growing stock. At some point, the land simply cannot sustain adding that much growing stock year after year without eventually exceeding its ability to sustain that forest. In other words, it will exceed its carrying capacity and become increasingly susceptible to bugs, disease, drought, fire, etc.

[I can’t find it on the web but Bowyer had quiz he gave his students to gauge their knowledge of environmental issues. They failed miserably! I can’t help but think popular rhetoric and newspaper articles such as this one had a lot to do with that.]

Indeed, also, since we are hardly even replanting forests, maybe we should close down our Federal nurseries and seed banks, letting ‘Whatever Happens’, happen, eh? With climate change, and since humans are part of nature, maybe we should just “let nature take its course”, and see what “Gaia” will bring us, eh? Again, we can plan for drought, bark beetles and firestorms…. or not.

At least here locally, since the feds are not harvesting, there is no need for seedlings and nurseries. Many millions of dollars are rotting/rusting away in their seedling storage facility. Except for a geneticist or two who still maintain their research, the seed orchard has not been used in years. As a taxpayer, I find it troubling to find such an investment going down the drain. Sure, we can plan for drought, bark beetles, and firestorms but planning and taking action are two very different things. I know a fellow who once had a thriving reforestation business with 30 some employees. When the feds quit planting trees, his business went belly up. [He then went back to school, earning his BS, MS, and his PhD.]

Hey Dick,

Just the U.S. Forest Service (not including the BLM) in Region 6 offered 617 MMBF of trees for sale in FY 2016.

And they offered 577 MMBF of trees for sale in FY 2015.

I love how just the U.S. Forest Service (not including the BLM timber sale program) offering up almost 1.2 Billion board feet of trees for sale in the past two years equates to “The feds are not harvesting.”

617 MMBF is still well short of the 1 billion BF target in the NW Forest Plan.

617 MMBF is much closer to 1 billion board feet than it is to “the Feds not harvesting.” (and again, the 617MMBF and 597MMBF is ONLY USFS lands in Region 6, not also BLM lands. But whatever….

Right, and the 1 billion board feet target was to have been from the NW Forest Plan area, not all of Region 6.

Right, and the NW Forest Plan area includes all or part of Region 5’s Klamath, Lassen, Mendocino, Modoc, Shasta-Trinity, and Six Rivers National Forests.

True, Andy — thanks. I should have added that. I reckon we’ve all wandered a ways from the original post.

Any way you look at it, Oregon’s federal forests harvest just 7% of its annual growth and, as Mac notes above, Montana harvests 4.6%. So, yes, that is certainly more than “no harvest”. But compared to what these forests are capable of producing, it is a pittance. I don’t know what the ASQ is but I suspect it is also a pittance. Even if that Montana mill produces a given quantity of lumber with a much reduced workforce, imagine the numbers of people who could be gainfully employed by modern, efficient mills if federal forests produced a quantity closer to its annual growth. Besides employing more people, I suspect it could greatly reduce our dependence on imports, reduce the risk of importing foreign pests (e.g., emerald ash borer, Dutch elm disease, etc.), reduce the exporting of the environmental costs of our consumption (an “ethically bankrupt position”), and have a positive impact on the nation’s balance of trade deficit. [Steve – does that bring us back towards the original post?]