Smog the Golden! Mythical Pyrodactyl aka “Smokey Dragon” (Frank Carroll, PFMc)

The following interview by Jim Petersen with Frank Carroll is nearly 2800 words long — which is kind of excessive for this forum but well worth the read for anyone who hasn’t done so already and is concerned with USFS wildfire history, politics, and economics over the past 35 years.

The interview is nearly four years old, but has just been republished in the current issue of Smokejumper magazine by editor Chuck Sheley and is a slightly abbreviated version of Petersen’s April 2020 publication in Evergreen Magazine: https://www.evergreenmagazine.com/blowtorch-forestry/

Despite the interview’s age, it remains directly relevant to current discussions regarding the great cost, visual and air pollution, wildlife mortality, and damaged rural economies resulting from continuing practices of the modern US Forest Service — what Carroll refers to as the “New Wildfire Economy.”

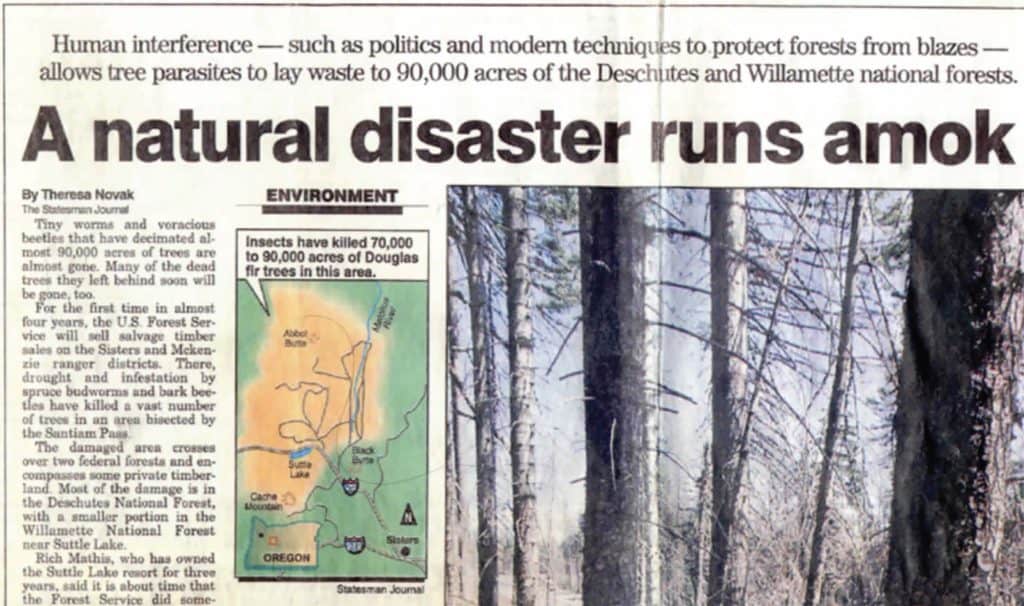

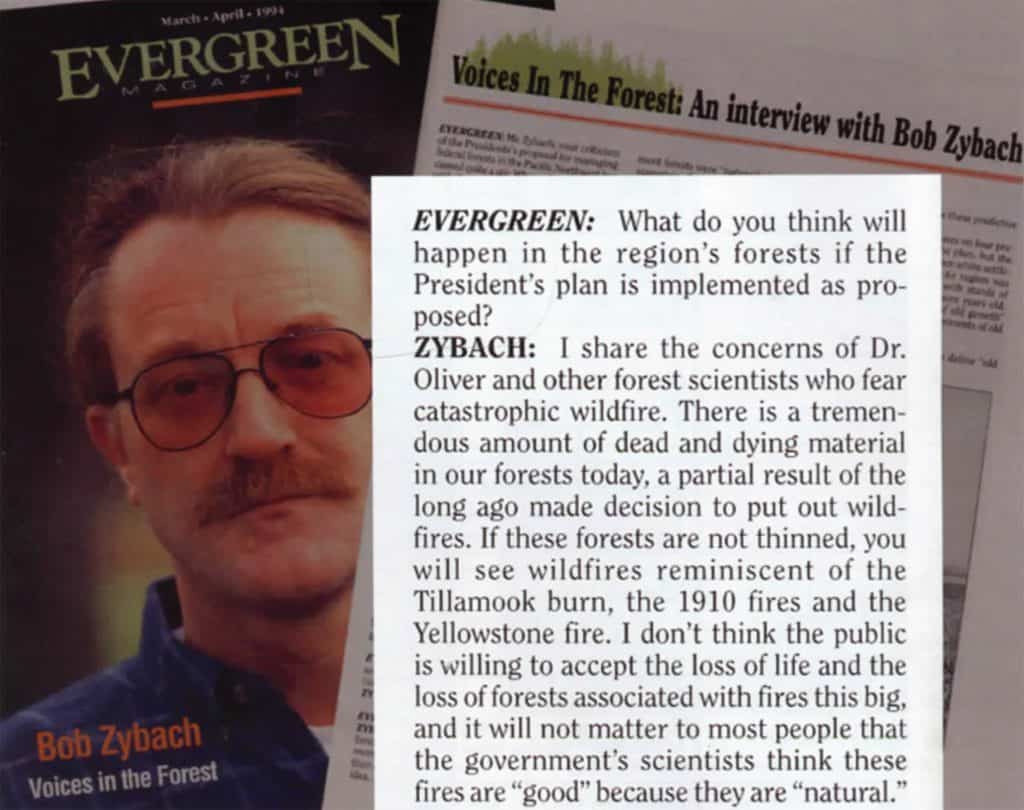

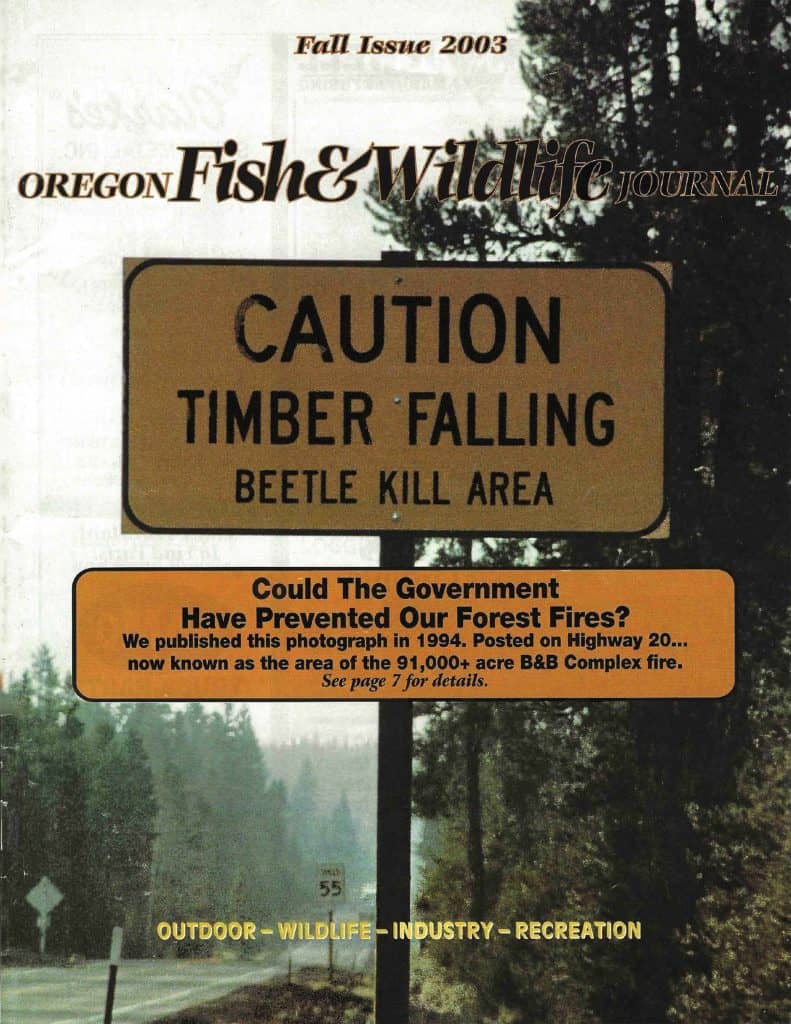

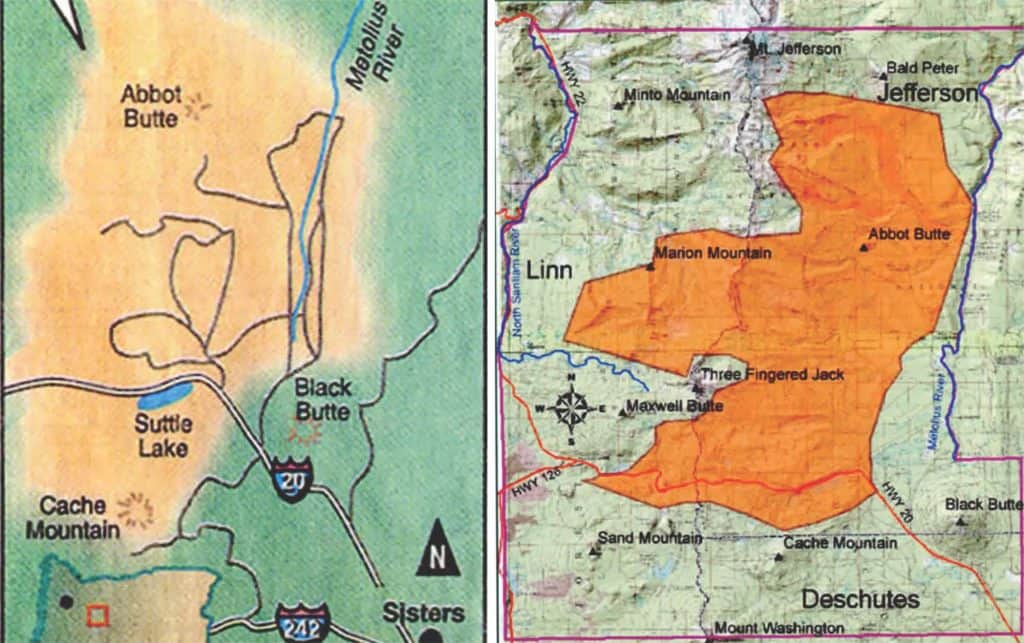

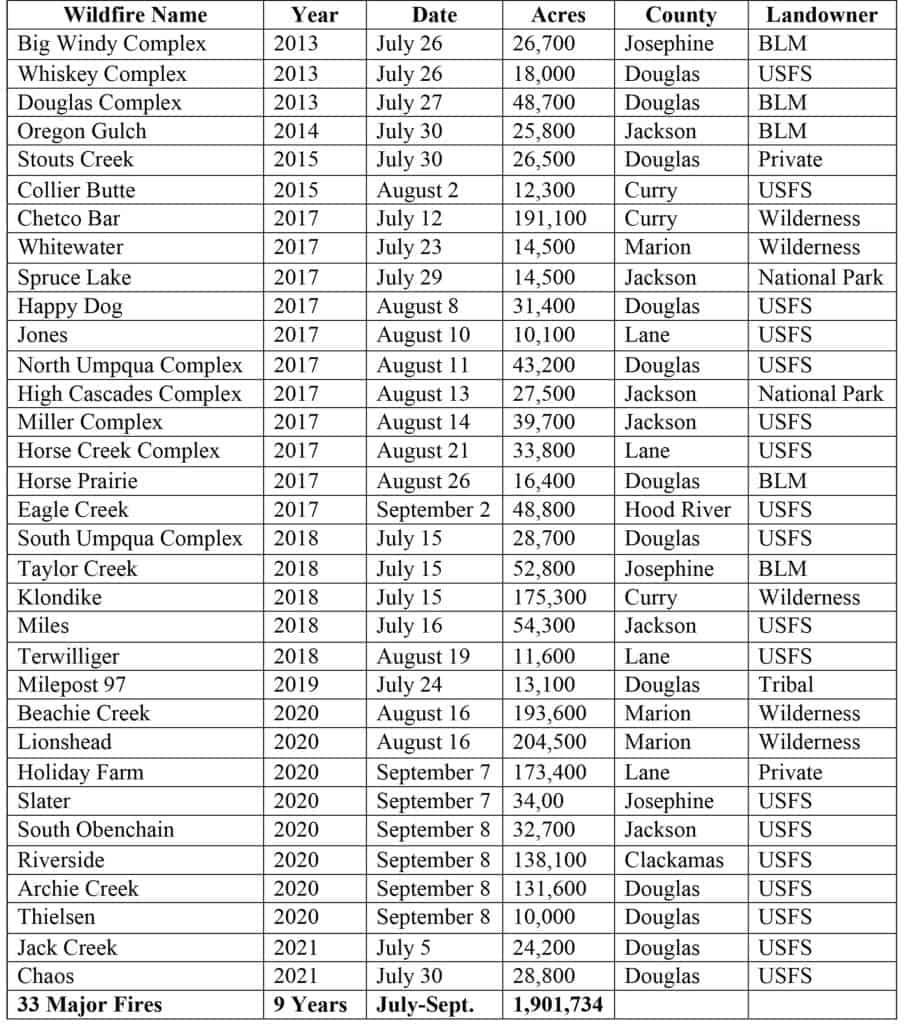

In 2020, then-USFS Chief Vicki Christiansen’s directive was: “Using unplanned fire in the right place at the right time.” Today, current-USFS Chief Randy Moore says he is “pleased to report that we have made significant progress in implementing this daring and critical strategy,” and talks about “using” fire on a “record 1.9 million acres as a method of reducing hazardous fuels.” If that is the objective, then much safer and cheaper methods of reducing such fuels — and even showing a taxable income while doing so — were demonstrated over hundreds of millions of acres in the 20th century and continue to be effectively used on private, state, and Indian lands to this time.

According to Carroll, the “New Wildfire Economy” has become “big business” for the USFS, “effectively replacing traditional forestry practices with unfettered wildfire tending.” This is presented as the difference between producing tax revenues for the government while creating needed local jobs, safe and beautiful environments, and maintaining abundant and diverse wildlife populations vs. using taxpayer dollars to economically bankrupt our rural forest economies, killing our wildlife, and replacing the once beautiful landscapes with a sea of ugly and dangerous snags. Not in those words exactly, but documented factual outcomes.

Sheley, Petersen, and Carroll are all experts regarding the responsible treatment of “unplanned fires” and the consequences for mismanaging them. Petersen’s book on the topic and Carroll’s qualifications are described in the interview and Sheley’s introduction:

*********************************

Chuck Sheley: I found Jim’s interview of Frank Carroll, a Colorado forester and wildfire expert, to be educational and informative and something the readers of “Smokejumper” magazine would find interesting. Jim’s book, “First Put Out the Fire,” leads off the discussion. This interview is from several years ago, and during COVID, but very relative to what is going on today. I’ve shortened the word count to make it fit in this issue. Reprinted with permission.

Jim Peterson: I’ve yet to hear from anyone who thought my book wasn’t “a good read,” but Frank Carroll, a colleague of 20 years, thought I stopped the wildfire discussion 20 years too soon.

Frank was Public Affairs Director for Potlatch Corporation’s Eastern Region when we met in 2000. Today, he is the Managing Partner in Professional Forest Management (PFM), a Pueblo, Colorado, firm that does trial work with clients whose private forests have been overrun by “managed fires” that began on adjacent Forest Service land.

Frank wrote: “I just finished your book and have to say I have high hopes for your book. I thought you would step above the old swamp and take on the biggest gorilla in the room, ‘using unplanned fire in the right time and the right place’ to ‘reintroduce fire to fire depleted ecosystems’ as Chief Christiansen put it in her directive to the troops last year.”

“Using unplanned fire in the right place at the right time” appears in a note Forest Service Chief Vicki Christiansen sent to her line officers last year. It is a thinly veiled reference to “managed fire,” or applying wildfire like prescribed fire, in a directive agency fire crews are expected to follow whenever the opportunity to let a wildfire run presents itself. There are few places outside of designated Wilderness areas where this can be done safely, but the practice is used widely across the Western National Forests as a matter of policy. Certainly, nowhere near communities, municipal watersheds, or fish or wildlife habitat critical to threatened or endangered species, and, yet, it is precisely these locations that are increasingly overrun by managed fire.

Some people rejected forestry long ago. State foresters, Interior agencies, and local governments have stayed the course where wildfires are concerned. Put them out as quickly as possible. Hence, the title of my book: First, Put Out the Fire. I write that if we don’t put these fires out, we won’t have anything else to talk about after the smoke clears. So, by all means, let’s talk about a proper role for wildfire in a post-industrial society that depends on its national forests for far more than timber.

Appropriately, timber production has become a by-product of federal policies that favor wildlife habitat conservation. In my opinion, “managed fire” is on a collision course with every forest value our society holds dear, which brings me to what’s bothering Frank Carroll.

I’ll let Frank speak for himself in the question-and-answer interview below, but his main complaint is one with which I am familiar— “managed fires” have a nasty habit of becoming unmanageable wildfires that overrun adjacent and well-managed private forest lands.

Petersen: Frank, tell us about your new business venture.

Carroll: Professional Forest Management, LLC, does wildfire impact analysis for law firms and private clients in federal tort claims and legal actions. From a forest perspective, this rather simple aspirational objective—using unplanned fire in the right place at the right time—is the absolute worst development in the history of forests and forest conservation.

Petersen: How so?

Carroll: We are burning our forests to ruin, and we’re doing it on purpose. We got out of the thinning and prescribed fire business on federal land, and now we are in the Age of Fire for Fire’s Sake. I call it “Fire-first” forestry. Federally-funded wildfire crews are burning big boxes around the West and are now responsible for 40 to 60 percent of the acreage burned by any given large fire.

Petersen: And this is managed fire?

Carroll: This is managed fire. National forest supervisors are expected to maximize the management role of wildfire, and they are doing it with a vengeance.

Petersen: This doesn’t sound like good forestry.

Carroll: It isn’t, but it is what’s happening. The 2018 Pole Creek and Bald Mountain Fires in Utah and the earlier Lolo Pass Fire are great examples of the madness of managed fire. We are working on $40 million in claims on Bald Mountain and Pole Creek alone, and there are many more that will go unchallenged because there is no internal or congressional oversight.

Petersen: What does that mean?

Carroll: It means the USFS is violating the National Environmental Policy Act. These fires are major federal actions with environmental consequences. Where are the Environmental Assessments or the Environmental Impact Statements? They don’t exist. There is no Record of Decision, no public process, no paper trail, no recourse for the public. The agency can operate in complete secrecy without disclosing specific or cumulative consequences. It’s all illegal. You cannot use Congressionally-appropriated fire suppression funds to do resource management except wildfire suppression. If you or I did this, we’d be in jail.

Petersen: Yet from what I’m hearing, “using unplanned fire in the right fire in the right place at the right time” is currently giving way to more timely and direct attack.

Carroll: Congressional delegations from the West forced Chief Christiansen’s hand because of concerns about the impact COVID-19 will have on firefighting this year. She is suddenly in full suppression mode because of the risks the virus poses to crews that work, eat, and sleep in close proximity.

Petersen: I understand that, but how does it undermine managed fire?

Carroll: The virus prevents the Forest Service from operating in complex strategic environments that feature big, intricate burnouts covering hundreds of thousands of acres because they can’t coalesce in one giant fire camp and coordinate all the moving parts. But you can be sure they’ll be back to “using unplanned fire” as soon as possible.

Petersen: Why?

Carroll: First, because they can. It’s a management prerogative they control completely and requires no public oversight or interference from cooperating agencies. Even when cooperators protest, as the State of Utah did in 2018, the Agency moves ahead anyway without consequences. Second, they are strongly pressed by environmental groups like FUSEE and the DiCaprio Foundation to let fires burn. And, finally, fighting forest fires has become big business for the USFS and their firefighting contractors—a hog’s paradise allowing them to spend money like drunken sailors. So, no one realizes what they are doing except the special interests who want them to do it, and an ignorant Congress is giving them limitless money to burn. So, they burn.

Petersen: How do you know all this?

Carroll: It’s our business nowadays. We do the intensive and comprehensive analysis of entire records from large fires. We spend years in deposition and preparing for court and trial. Our sources keep us abreast of new developments in policy and practice in real-time. In its reports to Congress, the USFS is counting wildfire acres burned as acres treated.

Petersen: We’ve heard that before and it has always seemed like a misappropriation of taxpayer dollars.

Carroll: It is. The USFS is using federally appropriated wildland fire management dollars to practice a new kind of wildfire-based resource management that holds that, since we can’t do real natural resource management projects on an ecologically significant scale, we’ll just use wildfire on everything everywhere and call it good enough. Managed fire is the only form of management no one questions. Environmentalists can’t stop them and don’t want to, they don’t need anyone’s permission, and there is no oversight.

Petersen: Real resource management being the thinning and prescribed fire regime that states, private landowners and Indian tribes use perennially?

Carroll: Correct

Petersen: This goes back to my belief that the fault here rests with Congress and its failure to allow the USFS to undertake forest restoration projects on physical scales that are environmentally significant.

Carroll: It’s worse than that. What we have here is a federal forest management agency that can spend whatever it wants in any way it wants with no public input or oversight.

Petersen: Aren’t there auditors who go through the firefighting bills?

Carroll: There are, but no fiscal officer in the USFS has firefighting experience. They won’t challenge or second guess fire commanders or forest supervisors because if things go to hell, they’ll be blamed. This is the new Wild West and Wildfire is the name of the game.

Petersen: Keep your head down and don’t mess up.

Carroll: Climate change, fuels equilibrium, growth, harvest and mortality, and reforestation are all yesterday’s news. What we have today is a rogue federal agency burning its way into a new bureaucratic empire that is publicly unaccountable.

Petersen: Reminds me of Eisenhower’s warning about the dangers posed by what he called the military-industrial complex.

Carroll: That’s a good analogy. What we have here is an Industrial Wildfire Complex that is answerable to no one. The Forest Service today is a much different agency than the one that all of us knew for decades. The transition from forestry to fire has rendered every forest plan objective effectively moot.

Petersen: That’s a big statement, especially when we consider that this transition occurred in plain view of anyone who was watching. And you worked for the Forest Service, didn’t you?

Carroll: In the National Park Service and the Forest Service from 1972 through 2012. I held primary fire, forest staff, and leadership roles in the USFS in Arizona, New Mexico, Idaho, South Dakota and spent time in Washington, D.C. My time since my Forest Service years has been spent in wildland fire mitigation planning and implementation, remote sensing, wildfire impact, and suppression analysis.

Petersen: Based on all your experience, how do we reverse course?

Carroll: Not easily. The Forest Service today is a black box. It is immune to public scrutiny and led by fire officers who are not well-grounded in natural resource management. They have no interest in further fights with smoke regulators or anti-management environmentalists. Why would they when they can burn far and wide, accumulate political power, maintain their Smokey vibe, and enjoy vastly increased budgets in the New Wildfire Economy.

Petersen: New Wildfire Economy. I don’t even like the sound of those words.

Carroll: No one should, but it’s real and it’s here.

Petersen: Some of these big fires burn so hot that they cook the soil. It can take a century or more to rebuild the organic layer in which seeds germinate, so 200 to 300 years to grow a new forest where the old one stood.

Carroll: That’s true and the burners don’t care. They see big wildfires as a natural agent.

Petersen: Better than the thinning and prescribed fire combination I describe in my book.

Carroll: Yes, because the New Wildfire Economy makes it easy. No appeals or litigation. No nasty wild-eyed environmentalists. Just lumbermen who don’t seem to understand the problem or are under too much economic pressure to have any stomach for the fight.

Petersen: So, where is the good news?

Carroll: The good news is that the Forest Service will not go to public trial on these issues for fear of upending their new wildfire hegemony. They are doing their own version of stop, drop and roll so they can stay hidden in plain sight. They will settle every claim out of court, no matter how weak, rather than go to trial and have these issues openly reviewed. This is good for people harmed by these fires.

Petersen: The big issue is the transition from an agency that manages forests to one that favors applied wildfire to every natural resource management objective?

Carroll: That is precisely the biggest issue. It is the issue that has the USFS hiding behind things like 747s that dump fire retardant on fires. It makes great video on the evening news but does nothing to address the underlying causes of these enormous fires or the agency’s decision to favor fire over forestry.

Petersen: We’re told the public is very suspicious of thinning projects that are large enough to actually reduce the risk and size of these big wildfires.

Carroll: Some people don’t like logging of any kind. Others see its value. In our New Wildfire Economy, it doesn’t matter. Welcome to the world of blowtorch forestry.

Petersen: More than half the Forest Service’s annual budget is spent on wildfires. Most people think that’s what it takes to put these fires out. You’re saying the big expense occurs when the decision is made to “manage” the fire, meaning let the fire run rather than put it out quickly.

Carroll: That’s correct. I can show you one 1,600-acre managed fire that cost taxpayers $12.6 million. The whole idea of firefighting has been turned on its head. The USFS is using crews to light fires on an epic scale, not put fires out. They have no idea what they’re doing or what the implications of using unplanned fire are for the future.

Petersen: Maybe Congress needs to tell the USFS that for every blowtorched acre there will be an acre that is mechanically thinned in combination with prescribed fire. The way it was done for decades.

Carroll: Nice idea but it won’t happen.

Petersen: Why not?

Carroll: Two different worlds. In the blowtorch world, the USFS burns to its heart’s content with no oversight, no need to ask anyone for permission and no lawsuits. In the world of forest and range management, there are laws and regulations, there is oversight and there is litigation. Moreover, the Forest Service no longer has the skill sets needed to plan and execute large scale thinning projects.

Petersen: So, we’re stuck with blowtorch forestry?

Carroll: The Forest Service—and Congress by association—are rolling big dice. They are betting that blowtorch forestry will reset the biological clock in our forests and that they will be able to meaningfully manage the resulting brush fields for the greater good. That’s just a fantasy.

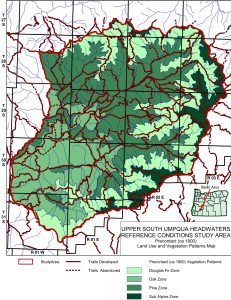

Petersen: Brush fields have overtaken much of the 500,000-acre Biscuit Fire that burned in 2002 on southern Oregon’s Siskiyou National Forest.

Carroll: You haven’t seen anything yet. Blowtorch forestry is creating millions of acres of sorrel monocultures that will burn and reburn and revert to the lowest common denominator, cheat grass and wild oats, like we’re seeing in California. The only way they can manage these newly created brush ecosystems is to keep burning them and the only time they can burn them is in high fire season. So, the blowtorch will be applied relentlessly until the world changes.

Petersen: There are still some dedicated professionals working for the Forest Service. I’m surprised no one has blown the whistle on this racket.

Carroll: I know, but you must realize that the USFS has no intention of returning to its roots. It has embraced wildfire because it’s easier. My partner and I are doing very well in this environment, but it’s so sad to watch.

Petersen: So, if I have followed the bouncing ball to its destination, what you are telling me is that the Forest Service will work harder on initial attack this year because the virus and the western congressional delegation have forced their hand.

Carroll: That’s correct. And because of much better initial attack—and no managed fires—you will see smaller fires this year unless they just let them burn, which is likely because moving armies around will be harder in most cases. But as soon as the virus passes, the Forest Service will go right back to blowtorch forestry.

Petersen: Unless we can find a way to stop them from burning the nation’s federal forest legacy to the ground.

Carroll: I am not optimistic. The forces that gave us a five-fold increase in fire suppression spending will not abate. The current Forest Service Chief is deeply and personally invested in the ascendance of fire management in her agency. The Deputy Secretary of Agriculture over the Forest Service is likewise a fire-first leader and the current Chief’s mentor. There is a fire dragon walking the halls of the Forest Service in Washington, D.C. and it will not be easily dislodged.