There are even a few court opinions dealing with plan-level decisions!

FOREST SERVICE

Court decision in Western Watersheds Project v. Perdue (D. Ariz.)

On September 29, the district court upheld the Stateline Project, reauthorizing livestock grazing for ten years on fourteen allotments on the Apache-Sitgreaves and Gila National Forests. Plaintiffs had argued that the Forest Service violated NEPA and the APA when it authorized the Project by failing to: (1) take a “hard look” at the Project’s impacts on Mexican Wolves, the Blue Range Primitive Area, and inventoried roadless areas; (2) prepare an EIS based on the context and intensity of the Project; and (3) consider a reasonable range of alternatives (there were two: no grazing and a 3% reduction from current AUMs).

Court decision in Blue Mountains Biodiversity Project v. Trulock (D. Or.)

On October 5, the district court upheld the Camp Lick Project on the Malheur National Forest. The Project would harvest trees larger than the 21” limit imposed by the Eastside Screens included in its forest plan because the Malheur properly amended its plan to allow this project. Plaintiffs had argued that the issues addressed by the amendment were forestwide, so the amendment (and therefore the effects) could not be limited to particular project, but the court disagreed. Instead the court agreed with the magistrate judge’s conclusions that NFMA “(i) does not require that the U.S. Forest Service identify a “unique” attribute present at the location of a site-specific amendment within a forest plan and (ii) does not require a finding of de facto significance whenever a site-specific amendment shares similarities with past or future amendments.”

(In response to Sharon’s question here, this opinion does not address whether removing these larger trees was necessary to reduce fire risk or what the effects of removing them would be. That may be because the administrative record adequately addressed these issues so they were not raised by plaintiffs.)

Court decision in Helena Hunters & Anglers Association v. Moore (D. Mont.)

On October 11, the district court upheld the Helena-Lewis and Clark national forest’s revised forest plan against challenges related to grizzly bears and big game – in particular the “removal” of wildlife standards that had been in the old forest plan and would benefit these species.

Interestingly, the government attorneys tried to claim that this was an original plan rather than a plan revision, despite a record full of references to a “revised” plan, because the two national forests had been combined subsequent to the first forest plans. The court concluded it is a revised plan, and dismissed the significance of this argument (but if it were a new plan, it would have been more difficult for plaintiffs to complain about “removal” of the wildlife standards). The court also refused to buy the government argument that the former standards were “largely carried forward” by equally effective guidelines and desired conditions, holding that these other plan components do not have “the same strength or impact” as standards. However, it was sufficient under ESA for the Fish and Wildlife Service to address the old wildlife standards as part of the environmental baseline, and to address the “general” effects of the revised plan without those standards.

The court held that NEPA’s requirement to look at the environmental consequences of the revised plan does not mean it has to look at the effects of individual plan components (or their “removal”). However, it did refer to the the plan components included in an EIS for the multiple-forest Grizzly Bear Amendment that were added to the existing plan prior to the revision, and are part of the revised plan. The court also held that the FS was not required to consider an action alternative that retained the wildlife standards, because, “Plaintiffs fail to demonstrate that the proposed alternatives are otherwise unreasonable.”

Useful word for the day (from the opinion): “defugalty:” an inconsistency, especially with regard to forms of communication.

Court decision

On October 15, the Oregon district court dismissed an antitrust lawsuit against Iron Triangle and Malheur Lumber by a group of sawmill owners, logging contractors and timber owners who accused the defendants of engaging in anticompetitive business practices. The court held that the 10-year stewardship contract with the Forest Service “is not an illegal conspiracy in restraint of trade.”

Best oxymoron for a business name: Prairie Wood Products

Court decision in Gallatin Wildlife Association v. Olson (D. Mont.)

On October 19, the district court dismissed a challenge to seven grazing allotments on the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest based on their effects on bighorn sheep. This followed the Forest Service losing a prior court case involving these allotments that required additional analysis, and an EIS was pending. Court found no unreasonable delay because the Forest was “not required to undertake agency action beyond that which already has been taken.” The court also summarily rejected a challenge to a supplemental EIS prepared for the revised forest plan in response to another lawsuit involving bighorn sheep, and rejected a third claim because these plaintiffs had failed to raise it in their prior challenge to these allotments.

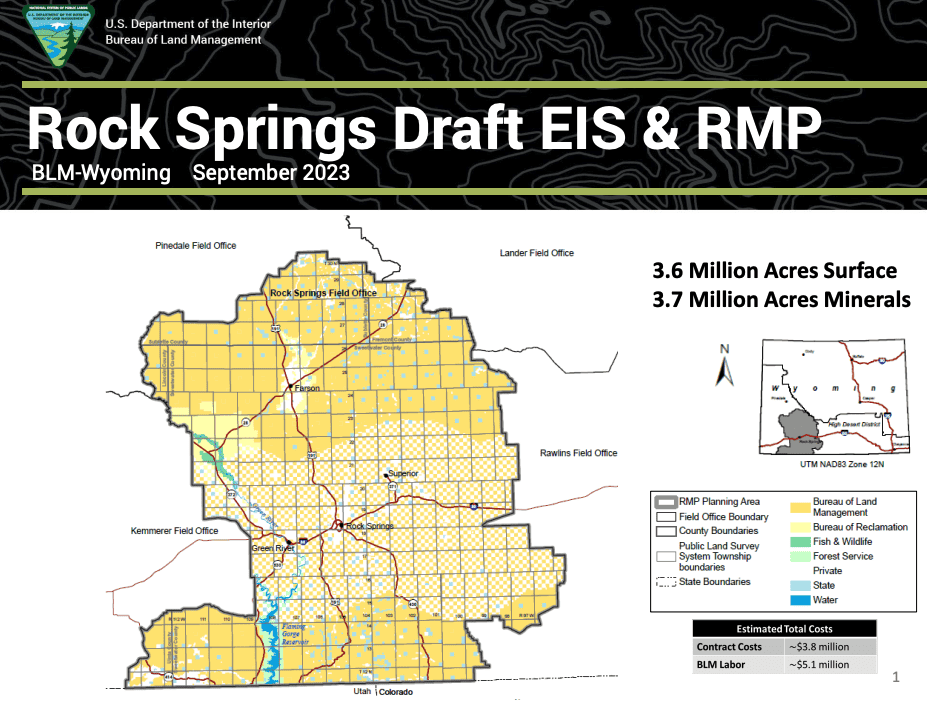

BLM

Court decision in Desert Protection Society v. Haaland (E.D. Cal.)

This case deals with the BLM’s decisions to amend the California Desert Conservation Area Plan and to grant a right-of-way to Eagle Crest Energy Company to construct, operate, maintain, and decommission a gen-tie [electrical] line and water supply pipeline. It would run through an area that had been designated as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern in the Conservation Plan. The larger energy project had been approved by FERC after an earlier NEPA process. On September 29, the district court upheld the BLM’s right-of-way decision against NEPA and FLPMA claims.

The NEPA claims involved decommissioning requirements, the range of alternatives, mitigation, and effects on acid rock drainage, groundwater, wildlife and global warming (which “largely concern the FERC Energy Project and not the BLM Right-of-Way Project”). Under FLPMA, the right-of way was not subject to other plan requirements because it was considered a “valid existing right.” BLM also met FLPMA requirements related to balancing interests, mitigation measures, collocation of right-of-ways, and the administrative protest process.

New lawsuit: Colvin & Son v. Haaland (D. Nev.)

On October 17, two ranchers in Nevada sued the BLM for delaying compliance with the Wild and Free Roaming Horses & Burros Act of 1971, which they say requires “immediate” removal of excess horses. BLM data showed that current populations are far above the “appropriate management level” established by the agency. (The article has a link to the complaint.)

Four individuals have been indicted by a federal grand jury on 13 counts of violating the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act by allegedly purchasing and then selling dinosaur bones valued at over $1 million and causing more than $3 million in damages, according to a statement from the U.S. Attorney’s Office, District of Utah. The value represents 150,000 pounds of paleontological resources, including dinosaur bones, illegally removed from federal (BLM) and state lands in southeastern Utah sold at gem and mineral shows and sometimes, China.

FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

Court decision in Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (D. D.C.)

On September 30, the district court held that the Service adhered to a reasonable interpretation of the ESA and followed proper procedures when deciding to downlist the American burying beetle from endangered to threatened status, despite noting climate change will pose foreseeable and grave risk to the beetle’s remaining populations in the coming decades. Ultimately, the Service proposed downlisting the species based on the agency’s conclusion in its 2019 study that the “beetle’s viability is higher than was known at the time of listing” and “it is not presently in danger of extinction.” The species’ historic range includes forests and grasslands in the eastern half of the U. S. (The article includes a link to the opinion.)

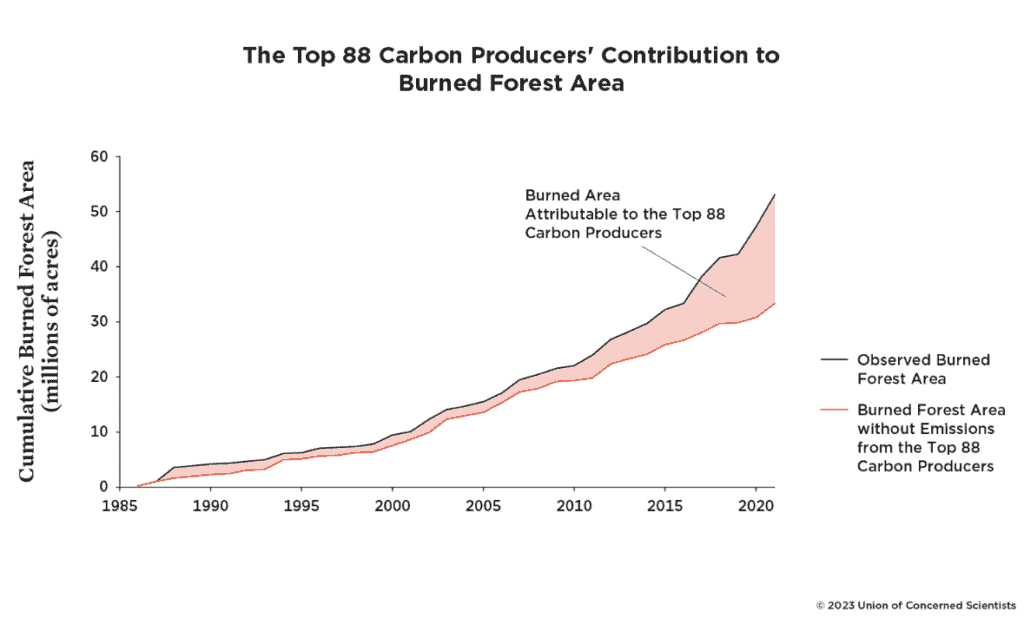

We have previously questioned whether/how national forest management has contributed to extinction of any species (where we discussed the ivory-billed woodpecker, which is still not officially on the extinction list). Here are some other possible examples.

In the continental U. S., this list of species removed from the protection of ESA because of extinction includes eight mussel species found in the southeast, where according to USDA, “Erosion, caused in part by deforestation, poor agricultural practices, and destruction of riparian zones, has led to both increased silt loads and shifting, unstable stream bottoms.”

The list also includes the Bachman’s warbler, a black and yellow songbird found in several Southern states, including on the Francis Marion National Forest. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, the Bachman’s warbler was also lost to destruction of its bottomland forest habitat.

OTHER

Settlement of Slockish v. U. S. Dept. of Transportation (Supreme Court)

This case involved the destruction of a Native American sacred site as part of a highway improvement project within the Mt. Hood National Forest. The parties to the case, which included the Yakama and Grand Ronde tribes, the Cascade Geographic Society and the Mount Hood Sacred Lands Preservation Alliance, agreed that the U. S. government would plant nearly 30 trees on the parcel and maintain them through watering and other means for at least three years. The government also agreed to help restore the stone altar, install a sign explaining its importance to Native Americans and grant tribal access to the surrounding area for cultural purposes.

A Bonner County District Judge recently upheld a decision by the Shoshone Board of County Commissioners denying a petition for road validation concerning a section of West Fork Pine Creek Road, which provides access to a section of BLM land with varying trails and roads throughout it – including “an area of specifically constructed off-road obstacles called the ‘Roller Coaster.’” The result is that public can be denied access to public lands on this private road.

If anyone is wondering how the northern spotted owl might have fared without the protection of the Endangered Species Act, Canada is now facing that scenario. Its Species at Risk Act requires an emergency order when an endangered species faces an imminent threat and before that threat materializes. The scientific recommendation to do so for spotted owls in British Columbia was ignored for eight months, allowing further logging of the forest that supports the last remaining wild-born spotted owl in Canada. A lawsuit was filed in June and heard in October.

The future of spotted owls in the U. S. might have looked like this:

“Today, however, only one wild-born spotted owl remains alive in all of Canada. Earlier this year, remains of two owls released from captivity in 2022 were found with their transmitters outside protected areas. The third was returned to the breeding centre where it is recuperating after being hit by a train… Foy was part of a team that visited the Fraser Canyon forest sites at the end of May. He said they found logging had already started in places where critical spotted owl habitat was meant to be protected.”