FOREST SERVICE

Court decision in Patagonia Area Resource Alliance v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Ariz.)

On September 1, the district court denied a preliminary injunction against the Sunnyside and Flux Canyon exploratory drilling projects in the Patagonia Mountains on the Coronado National Forest. The Sunnyside Project is a seven-year exploratory drilling project, requiring the construction of thirty drill pads within three drill areas occupying 7.5 acres. The Flux Canyon Project is a twelve-month exploratory drilling project, requiring the construction of about 2,000 feet of road and six drill pads disturbing 1.8 acres of national forest land. The court found plaintiffs would be unlikely to prove inadequate analysis of cumulative effects, effects on Mexican spotted owls and other species and water conditions in the EA for the Sunnyside Project or that Flux Canyon Project did not warrant a CE.

New lawsuits: Alaska v. U. S. Dept. of Agriculture (D. Alaska)

Inside Passage Electric Cooperative v. U. S. Dept. of Agriculture (D. Alaska)

Murkowski v. Vilsack (D. Alaska)

On September 8, the State of Alaska and two other groups of plaintiffs filed three separate federal lawsuits challenging the Forest’s Service’s repeal of the 2020 Alaska Roadless Rule and reinstatement of the national 2001 Roadless Area Conservation Rule on the Tongass National Forest, which restricts road construction. The lawsuit focuses on “prospective geothermal and hydroelectric power plants, as well as hypothetical metal mines whose products could be used for green technologies.” An attorney for a plaintiff said that logging companies aren’t part of these new lawsuits because logging is restricted under a new forest plan, and the prospects of changing the forest plan are limited (evidently referring to the 2016 “young growth” plan amendment). (The article includes a link to all three complaints.)

New lawsuit: Western Watersheds Project v. Haaland (D. D.C.)

On September 14, plaintiffs sued Clark County, NV and the Fish and Wildlife Service along with the Forest Service, BLM, and Park Service (and USDA and USDI) for failing to protect the Mojave desert tortoise and other rare species subject to the Clark County Multi-Species Habitat Conservation Plan (“MSHCP”). The Forest Service, BLM, NPS, and Fish and Wildlife Service all signed an Implementing Agreement, which binds them to implement the MSHCP. The MSHCP was created to offset the development of nearly 170,000 acres of land on the outskirts of Las Vegas that would destroy habitat for imperiled desert species, in exchange for mandatory conservation measures, which have allegedly not been implemented. Trespass grazing (by Cliven Bundy) and solar energy permits are among the activities being allowed to occur. Plaintiffs seek reinitiation of ESA consultation on the effects of the incidental take allowed by the MSHCP, and supplemental NEPA analysis.

New lawsuit: Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Mont.)

On September 20, the Center for Biological Diversity, the Council on Wildlife and Fish, and the Alliance for the Wild Rockies sued to stop the South Plateau Landscape Area Treatment Project just west of Yellowstone National Park on the Custer Gallatin National Forest. Plaintiffs say the 83 million board-feet of commercial timber expected to be removed is “significantly more than allowed under the Custer Gallatin National Forest Plan.” The Project would log mature forests using a condition-based approach to NEPA compliance that does not identify specific locations. However, it plans timber harvest or burning on 16,462 acres, including 5,531 acres of clear-cutting, 6,593 acres of other commercial harvest and 56 miles of roads in habitat designated for grizzly bears and Canada lynx. The article includes a link to the complaint. On September 6, the lawsuit parties also filed a notice of intent to sue under the Endangered Species Act (linked to this article).

New lawsuit

The Forest Service is suing three businesses alleging that smoke bombs — deemed illegal in California and used during an ill-fated gender reveal event — were defective, and sparked the deadly 2020 El Dorado fire in San Bernardino County. The suit, which alleges negligence and health and safety violations, seeks unspecified monetary damages for fire suppression and investigative costs and various adverse environmental impacts.

New lawsuit

Thirty-two Wyoming residents and organizations are suing the Forest Service for allegedly choosing to not suppress the 2018 Roosevelt Fire on the Bridger-Teton National Forest during “red-flag” fire conditions. The fire consumed more than 65,000 acres and burned 55 homes. Using an unplanned fire to achieve natural resource benefits isn’t authorized by federal law and violates the National Environmental Policy Act, the complaint says. The document also accuses the agency of failing to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act and failing to harmonize the act with the Forest Plan.

BLM

New lawsuit: Western Watersheds Project v. U. S. Dept. of Interior (D. D.C.)

On September 14, Western Watersheds and Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility filed a lawsuit accusing the Bureau of Land Management of failing to perform required grazing permit reviews across the West. PEER analyzed data from 1997 to 2019 on land health evaluations for BLM’s 21,000 grazing allotments, and found the 27% had not been evaluated for environmental impacts pursuant to NEPA, with an even greater proportion in important natural areas and wildlife habitat, including for sage-grouse. The plaintiffs argue that this violates 2014 and 2015 FLPMA amendment requirements to determine priority for environmental analysis and to conduct such analyses. The article includes a link to the complaint.

New lawsuit: Cascadia Wildlands v. U. S. Bureau of Land Management (D. Or.)

On September 19, Cascadia Wildlands and Oregon Wild went to court to stop the Big Weekly Elk Forest Management Project on the Coos Bay District. The Project decision is based on an EA, and includes logging uncommon mature and old-growth forests and habitat for marbled murrelets and northern spotted owls. The news release has a link to the complaint.

PARK SERVICE

Court decision in Earth Island Institute v. Muldoon (9th Cir.)

On September 12, the circuit court affirmed the district court’s denial of Earth Island Institute’s motion for a preliminary injunction to halt parts of two projects to thin vegetation in Yosemite National Park in preparation for controlled burns. The court held that the projects fell under the “minor change” categorical exclusion because they were “changes or amendments” to the 2004 Fire Management Plan that would cause “no or only minimal environmental impact.”

New lawsuit: Wilderness Watch v. National Park Service (E.D. Cal.)

On September 25, Wilderness Watch, Sequoia Forestkeeper and the Tule River Conservancy filed a complaint seeking to enjoin “Fuels Reduction Efforts to Protect Sequoia Groves in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks from the Devastating Effects of High-Intensity Fire,” authorized by a decision memo and using emergency NEPA procedures. Much of the tree cutting and burning would occur in designated wilderness, with Park Service arguing that is “necessary” to violate the Wilderness Act. The article includes a link to the complaint.

EPA

Settlement in Center for Biological Diversity v. Environmental Protection Agency (N.D. Cal.)

On September 12, the court approved a settlement agreement that commits the Environmental Protection Agency to develop a strategy to address the effects of over 300 active ingredients in herbicides, insecticides and rodenticides on ESA-listed species by 2025. A biological evaluation to address the harms of eight especially hazardous organophosphate insecticides on endangered species is required by 2027. The news release includes a link to the settlement and 2011 complaint.

FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

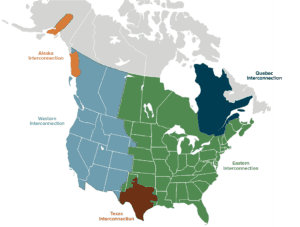

On August 31, the Fish and Wildlife Service listed four distinct population segments (DPSs, see map) of foothill yellow-legged frog under the Endangered Species Act. In the final rule, the Service identified altered hydrology, agriculture, illegal cannabis cultivation, predation by nonnative species, diseases and parasites, mining, urbanization, recreation, severe wildfire, drought, extreme flooding, and the effects of climate change as severe threats to the Frog The species is found on national forests, and was part of a recent lawsuit mentioned here.

Noah Greenwald, director of the Endangered Species program at the Center for Biological Diversity:

Grizzlies wouldn’t be roaming the greater Yellowstone ecosystem if it wasn’t for plentiful food, and the vast wildlands of the national park that offer protections from traps, bullets, chainsaws and bulldozers. But one of the most important places for grizzlies in recent decades has been the federal courthouse. I recently reviewed every lawsuit filed on behalf of grizzlies bears during the past 30 years and it’s clear that litigation has played a pivotal role in protecting these bruins under the Endangered Species Act, ensuring they survive and thrive.

When it passed the Endangered Species Act 50 years ago, Congress recognized that implementing the law would be difficult for agencies like the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service because of the likelihood of direct conflicts with powerful special interests. As an antidote, a provision was included in the law that allows private citizens to go to court on behalf of species like bears that can’t speak for themselves.

Dozens of lawsuits have been filed during the last few decades to stop logging, mining, road building, livestock grazing and other destructive projects in grizzly bear habitat. Recently the Center for Biological Diversity, where I work, stopped two massive timber sales in the Kootenai National Forest in northwestern Montana that threatened the endangered Cabinet-Yaak population of bears. The U.S. Forest Service wanted to clearcut hundreds of acres of old forest and construct miles of new roads, which would have had devastating consequences for the grizzly bears.”

And here’s the latest effort to protect grizzly bears in a federal courthouse. The lawsuit alleges the Idaho Department of Fish and Game killed a grizzly bear cub without authorization from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which also is named as a defendant for allegedly permitting two other bears to be killed contrary to federal regulations.