I think this is interesting; nice work by Steve Wilent in the Forestry Source so here goes:Introduced Species Forestry Source June 2013. Below is an excerpt.

I recently talked with Schulz to learn more about the inventories as well as her and Gray’s findings and what they tell us about introduced plant species. What follows is a portion of that conversation.

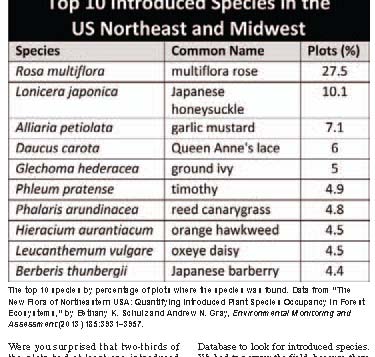

Were you surprised that two-thirds of the plots had at least one introduced species?

Yes, at first it was a big surprise. And then when we started looking at what species were coming out as introduced. When you’re dealing with thousands of plots and tens of thousands of species, you

need to go to a database to sort things out and find which species are introduced and which are native. We used the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Plants Database to look for introduced species.

We had to narrow the field, because there are many species that are natural in some areas and introduced in others. We tried to be conservative in determining which were the introduced species.

And there are many species that people aren’t aware are introduced, such as the grass timothy, which is easily recognized, and other benign species like common plantain. They are indeed introduced

species, but not every introduced species turns out to be a nasty ecosystem transformer.Many of the ones that do become transformers started off as introduced species, and sometimes they sit around in the environment for quite a while before something happens—some sort of disturbance—

that lets them start to gain ground and become more successful. It can be many years before they are recognized as being a species that may be of concern.

A couple of thoughts..I think she highlights that there are “bad” non-natives and “OK” non-natives. Non-natives are labelled “bad” for a reason. Which fits in with Lackey’s point in his paper here.

or example, in science, why is it that native species are almost always considered preferable to nonnative species? Nothing in science says one species is inherently better than another, that one species is inherently preferred, or that one species should be protected and another eradicated.

To illustrate, why do most people lament the sorry state of European honeybees in North America, a nonnative species that has outcompeted native bee species? Yes, our honeybees are nonnative, what many people would label as an invasive species, but people value their ecological role.

Conversely, zebra mussels, another common, but nonnative species are nearly universally regarded as a scourge. Where are the advocates of this species? Even with increased water clarity, no cheerleaders.

Or, what about North American feral horses — wild horses — mustangs! This is another nonnative species, but one that enjoys an exalted status by many. Would you want to be the land manager tasked with culling the ever-expanding population of this invasive, nonnative species?

Values drive these categorizations, not science.

But more pragmatically, there are many non-natives around. Any public money directed to their eradication (in my view) should be based on criteria including how “bad” they are specifically, to what; and (not inconsequentially) the likelihood of some kind of specific success.