This may be of interest to other folks…. dried grass and high winds are nothing new to the Front Range of Colorado. However, after the Marshall Fire, a concern over liability on the part of Xcel Energy may well be new, hence.. preventative as well as accidental outages.

From the Denver Post:

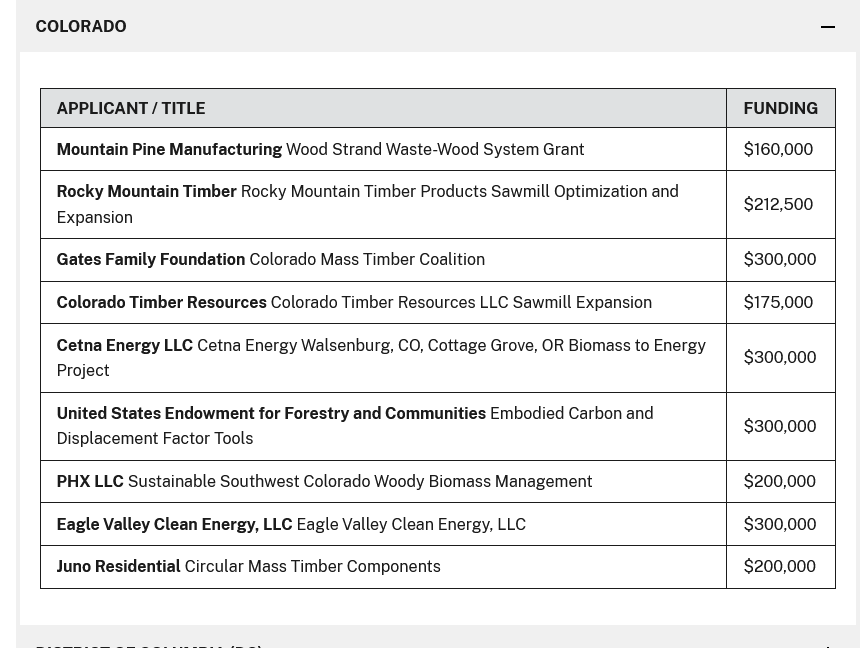

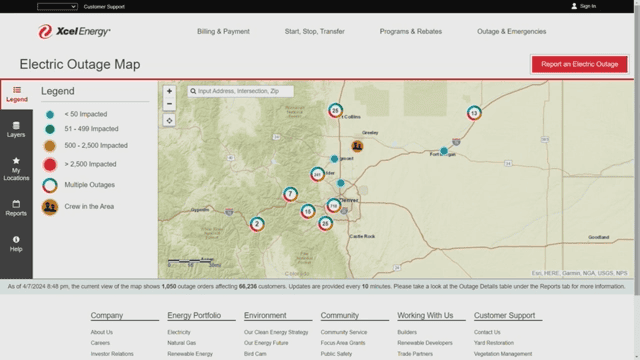

The news follows the utilities company’s Sunday prediction that it could take through Monday or longer to restore power to more than 87,000 Xcel customers statewide who were still experiencing outages by 5:45 p.m. on Sunday.

As of Monday morning at 10:25 a.m., over 750 outages were reported by just over 29,000 customers in the Denver area, whereas the Boulder area still saw close to 225 outages affecting roughly 12,000 customers, according to the Xcel electric outage map.

A total of more than 150,000 were impacted by the loss of power — severe weather caused outages for around 100,000 customers, while another 55,000 in six counties had their power shut off by Xcel in an effort to prevent wildfires.

“For the first time in Colorado, Xcel Energy conducted a public safety power shutoff,” said spokesperson Tyler Bryant in a Sunday statement. “While many customers will have service restored later today, with the significant number outages from this weather event, this restoration process will extend into Monday, April 8 and possibly longer for some customers.”

With more than 400 crew members working on restoring power to more than 600 miles of affected lines, the company had addressed the needs of about 63,000 customers by Sunday evening.

Because Xcel changed its system settings during the extreme winds to restrict automatic power restoration, “this safety measure means power outages are likely to last longer than they typically would,” Bryant said.

Since we have both high wind and dried grass in the winter, perhaps electrifying everything is not a very resilient approach? Just a thought. Also, on the app Nextdoor, there was a certain (large) amount of unhappiness with the way this rolled out (although Xcel had its defenders, and lots of appreciation for employees working to get power restored). A critique From one neighbor:

1. Confusing messages sent out before cutting off our power.

2. No map provided in advance that would have helped know if any businesses, friends, neighbors still had power.

3. Outage map provided after power cut off that is just as useless.

4. Automated emails sent after power cut off assuring us that they are working diligently to get the power back on. Which we know they are not.

5. Another automated email sent out asking what we think of the new electricity rate structure.

6. They have now said that people preemptively shut off have lower priority than those who lost power due to the storm 🤦 Hard to think how they could have done this any worse.

Another thought.. a human being might want to review automated emails prior to sending to see if they fit the current situation.

You all might remember this piece from the LA Times in 2019-

Pacific Gas & Electric cut power to more than 700,000 customers in 34 counties early Wednesday because of high winds. Some households were without electricity for 72 hours, a spokesman said. Southern California Edison shut off electricity to more than 24,000 customers, also starting Wednesday.

The biggest failure, experts and customers alike said, was communication. Residents complained they did not receive adequate notice of the shutdown or no notice at all and could not get on the utilities’ websites.

Lessons learned from the shutdowns are critical because more will take place, experts said.

“I suspect for the next few years these are going to occur,” said Severin Borenstein, faculty director of UC Berkeley’s Energy Institute. “No one involved in this thing thinks it was a one-time event.”

The California Public Utilities Commission on Monday ordered PG&E to take immediate corrective actions, and Gov. Gavin Newsom called on the utility to give residential customers who lost power $100 rebates.

Commission President Marybel Batjer told PG&E it must try to restore power within 12 hours in the future, reduce the size of outages, develop systems to ensure call centers and the website are accessible and develop a “communication structure” with counties and tribal governments so they can respond to emergencies.

“Failures in execution, combined with the magnitude of this … event, created an unacceptable situation that should never be repeated,” Batjer said.

He said the state should create some sort of committee that includes public safety officials, elected officials, utilities and the Public Utilities Commission to make power shut-off calls in the future.

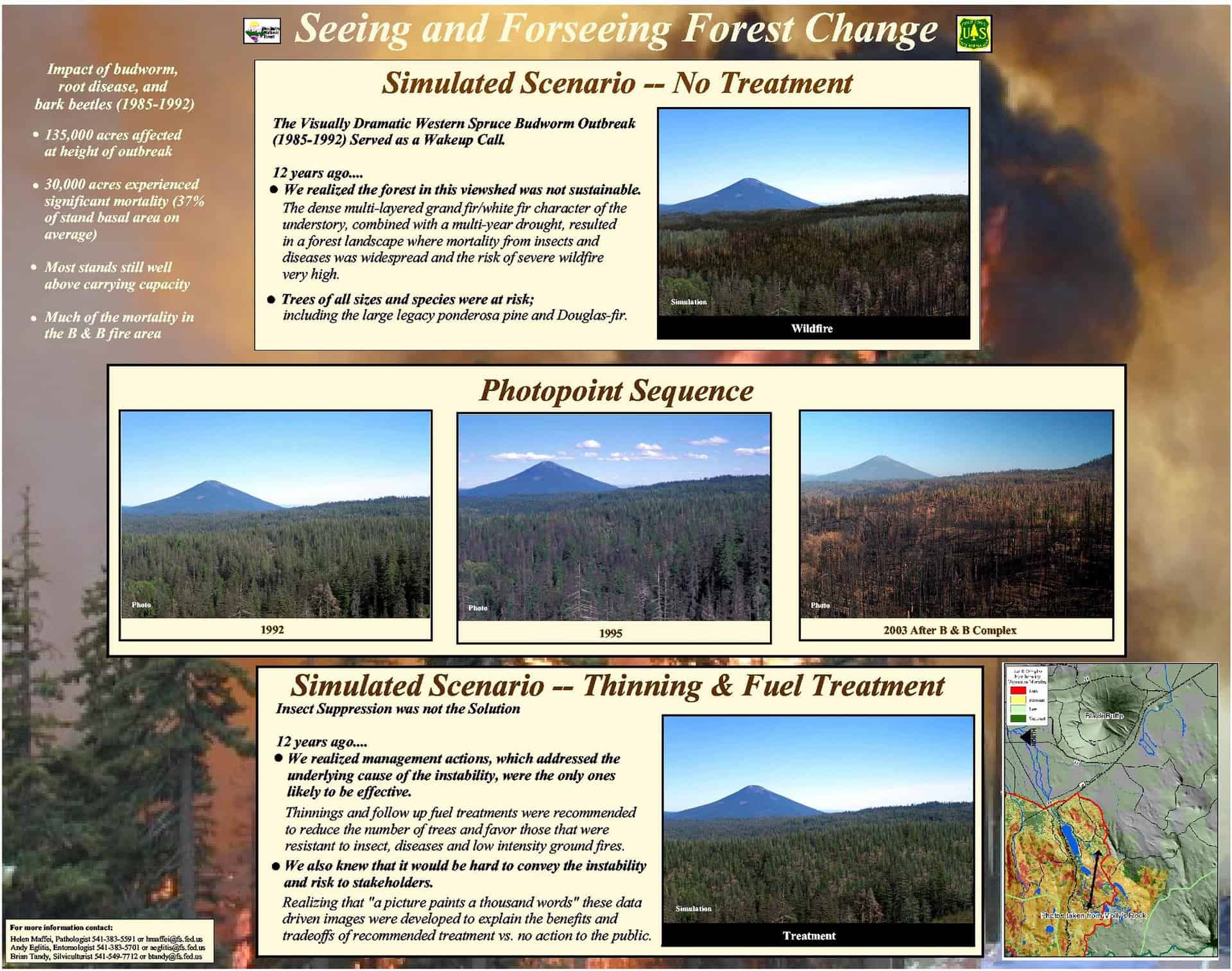

Utilities have sparked fires for decades, but they are now more destructive because of droughts produced by climate change and the movement of people into more remote, highly vegetated regions, experts said.

Southern California Edison’s customers complained the utility failed to give them adequate warning.

They hit the utility with questions about the timing, criticism over lack of immediate notice and outrage over spoiled food, stress-related health effects and fears that trapped cars beneath electric garage doors would leave people stranded in the event of a fire.

“We strive to keep the customer informed always, but we may not be able to depending on circumstances,” said Edison spokesman Robert Villegas.

Anyway, the article has interesting lessons learned and ideas for improvement (that could have helped Xcel) .. but given the warning timeframes, maybe it’s best to be ready for a shutoff, even if you live far from the WUI.

Here’s the PSA from Xcel:

Put together an outage kit

Include things like flashlights, batteries, portable chargers, a phone that does not require electricity, a non-electric clock, bottled water, non-perishable food, a manual can opener and a first aid kit

Make sure your computer is protected from surges

Keep devices charged

“Customers who use medical equipment that relies on electrical service should take steps to prepare for extended outages,” Xcel said.Other things to consider include lighting options for when the power goes out, using a cooler to avoid opening the fridge and using a generator.

“For customers with power outages, you may want to unplug appliances containing electronic components, such as televisions, microwaves, and computers to prevent damage as power is being restored,” Xcel said.

Last year, Sammy Roth wrote a piece on the problem of reliability with regard to tolerating more blackouts during the transition time to solar and wind energy storage technologies.

I got a similar reaction on Twitter.

Of the hundreds of people who responded to my question, most rejected the idea that more power outages are even remotely acceptable — for reasons beyond mere convenience. A former member of the L.A. Department of Water and Power’s board of commissioners wrote that “someone dies every time we have a power outage.” An environment reporter in Phoenix — where temperatures have exceeded 110 degrees for a record 20 straight days — said simply, “Yikes.”

Moura expanded on his skepticism by noting that modern life is more reliant on electricity than ever before.

Those of us lucky enough to have air conditioning depend on it to stay safe during heat waves — which can already kill thousands of people and are only getting more dangerous as fossil fuels warm the planet. Elderly people and individuals with certain health conditions are more vulnerable to heat illness and sometimes need electricity to power their medical equipment, such as ventilators, dialysis machines and motorized wheelchairs. Our refrigerators, cellphones and internet service all depend on reliable electricity.

“It’s not really about keeping the lights on. It’s about keeping people alive,” Moura said.

Two years ago this month, California narrowly avoided rolling outages after wildfire smoke knocked out electric lines that carry large amounts of power from the Pacific Northwest. The state again toed the precipice during a hot spell last September, fending off blackouts only after officials sent out an emergency alert to millions of mobile phones begging people to use less power.

Again and again, I’ve found myself asking: Would it be easier and less expensive to limit climate change — and its deadly combination of worsening heat, fire and drought and flood — if we were willing to live with the occasional blackout?

************

Indeed, solving climate change isn’t as simple as replacing gas and coal plants with solar and wind farms. We need to get tens of millions of electric vehicles on the road, and tens of millions of electric heat pumps in people’s homes. We also need to build a lot more long-distance power lines to move renewable electricity from where it’s generated to where it’s needed.

More powerlines, more maintenance, more cutoffs, more dependency on electricity.. maybe it’s time to rethink this?