Firefighters strategically used fire to reduce the existing fuel load as the Pass Fire approached the area, which saved the wooden corral structure.

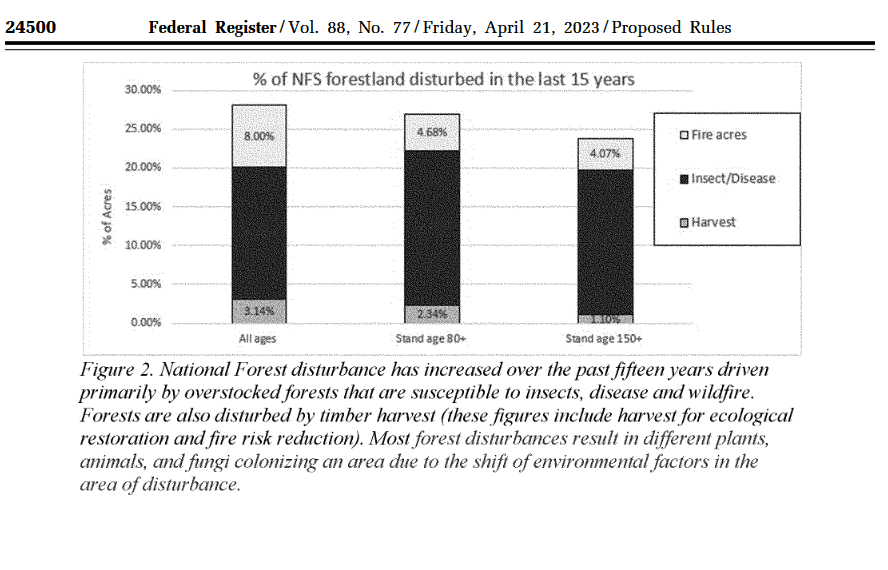

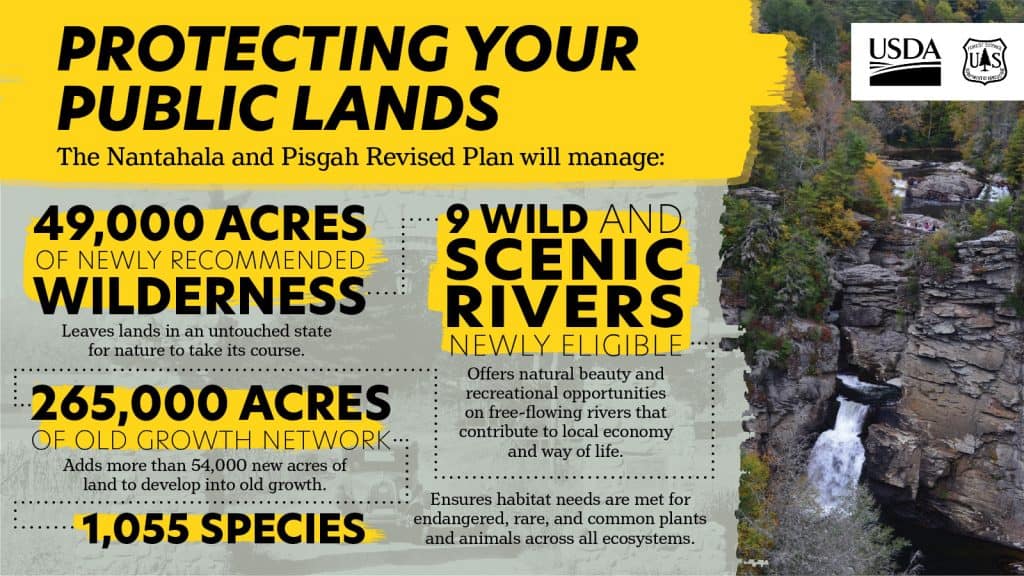

So, wildfires used to be bad. Enter Smokey Bear. But we wised up and discovered that we need to live with fire, and if we don’t want to have destructive wildfires, we need to manage fuels on landscapes including using prescribed fire and wildland fire use (see photo above). But as far as I can tell, if we’re not careful, we mix up WFU acres with “true” wildfire acres, and then use the total in statements about wildfires and climate. And if we do, we’re back where we started, assuming all wildfires are bad. Let’s not do that.

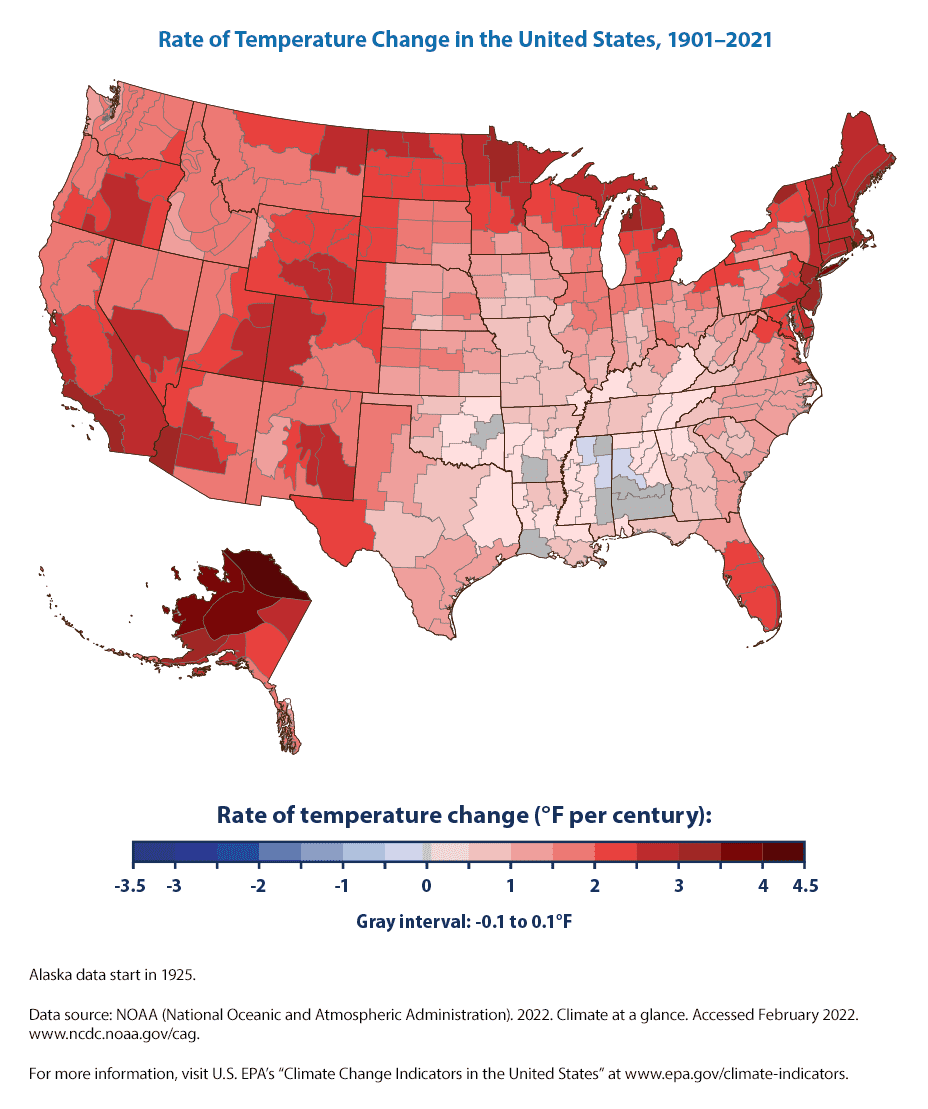

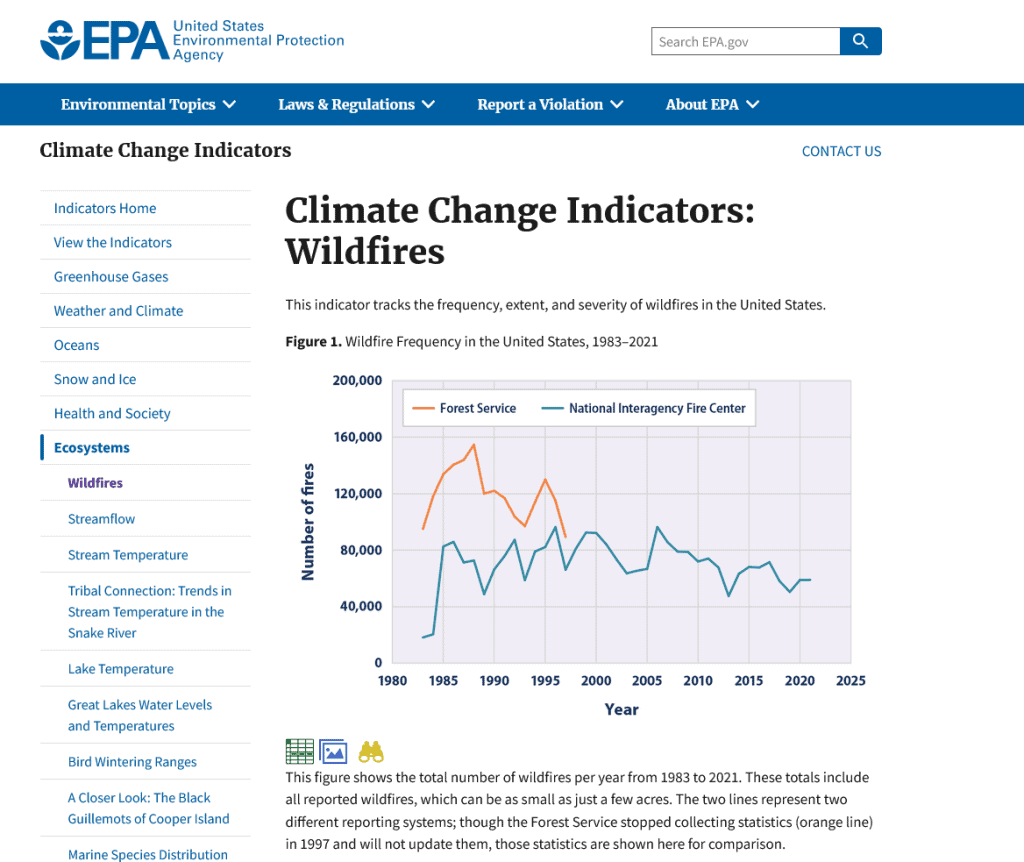

Or we could use numbers of wildfires like the EPA..

Is number of wildfires an indicator of climate change? Seems like before you made that claim you would have to separate human ignitions from lightning..

We hear that (1) wildfires are caused by (anthropogenic contributions to) climate change. And yet we know that not to be true, in a plain English sense of causality, as wildfires have long predated humans. If we pushed back, we might hear (2) “wildfires are made more likely due several factors, one being an increased frequency in some weather conditions conducive to wildfires and those that make firefighting more difficult, some or all of which is due to anthropogenic climate change (AGW).” So how does 2, which I think most of us agree on, mutate into 1? Sloppy public affairs folks?

Here’s what the White House said on June 8

More than 100 million Americans are under Air Quality Index Alerts due to smoke drift from historic wildfire activity throughout Canada, which is facing one of its worst wildfire seasons on record. There are over 425 active wildfires in Canada and nearly 10 million acres have burned, 17 times the 20-year average. Since January 1, 2023, 19,574 wildfires have burned 616,486 acres across the United States. Most current large fire activity in the United States is concentrated in the Southwest.

These latest events are another stark reminder of how the climate crisis is disrupting communities across the country. That’s why from day one President Biden recognized climate change as one of the four crises facing our nation, and why he made historic investments to tackle the climate crisis and strengthen community resilience.

So I suppose you can pivot from the Canadian fires to climate change but the US story is not exactly pivotable. And here’s what NIFC said on June 22, 2023 about the US.

Since January 1, 22,052 wildfires have burned 636,031 acres across the United States. These numbers are below the 10-year average of 25,006 wildfires and 1,478,575 acres burned.(my bold)

But to further complicate things, some of these fires here (and in Canada) are being managed for resource benefits.. or whatever the current terminology is.. (thanks to the Hotshot Wakeup for info on the Pass Fire) so more acres (without destroying things of ecological or human value) are actually a good thing. That’s what our folks have trained for, and what we all want done. As far as I know.

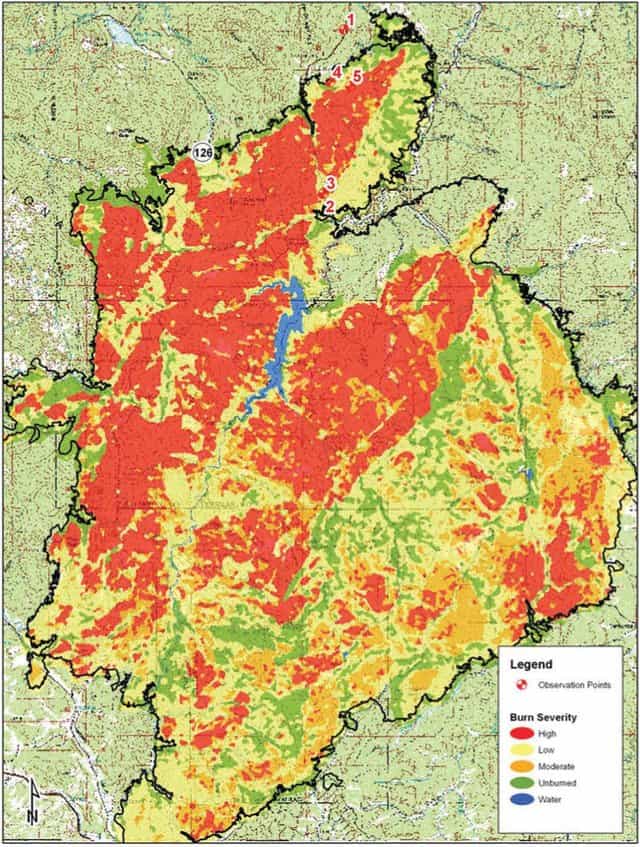

The largest fire is the Pass Fire in NM that shows 55, 683 acres as of today.

The overall strategy on the Pass Fire is to allow the low to moderate intensity of the fire to play its natural role on the landscape as firefighters take appropriate actions to keep the fire within the designated planned boundaries while protecting private land, infrastructure, and natural resources. The Gila National Forest is a fire-adapted ecosystem. It is dependent on fire to play a natural role in restoring the landscape to more natural conditions while preventing the occurrence of extreme fires in the future.

So for this fire, the largest one currently on the board, lots of acres are a good thing, attributed to good management and possibly to some good luck with weather conditions.

NIFC on the 22nd had this one, the Pulp Road fire, at 15,642, I think it’s at 16K or more now.

This fire was an escaped prescribed fire by the North Carolina Forest Service. Escapes tend to be caused by other things than AGW, but perhaps AGW could play a role.. we’ll have to see what the investigation discovers. Anyway, for this one acreage over the target is a bad thing, but dubiously attributed to climate change.

The next largest is the 10,279 Wilbur Fire on the Coconino

The Wilbur Fire is being managed with multiple strategies to meet suppression and resource objectives. Those objectives include the release of nutrients back into the soil and the reduction of hazardous fuel accumulations. Objectives also include protecting critical infrastructure, watersheds, wildlife habitat and culturally sensitive areas from future catastrophic wildfires.

Again, more acres here are good. I wonder if there’s a place where WFU acres are tracked separately from total acres, or how difficult that is to do. Wouldn’t it be great if we had a table that included:

Prescribed fire acres

Wildfire Use Acres

Unintentional Wildfire Acres

The sum of the above two (WUA plus UWA) would be the total wildfire acres.

Then the Unintentional Wildfire Acres (or True Wildfire Acres) could be broken down by

Lightning

Human with subcategories that included:

Escaped prescribed fires

Escaped WFU fires.

Arson

Accidents by individuals

Equipment (powerlines etc.)

Or maybe that table already exists somewhere?

For now, it’s June, the season’s off to a slow start here in the US, and let’s celebrate the folks who are successfully using managed wildfire!