I received a link to this article just about the same time I was hearing about the re-Monumentization effort and the language of the Reconciliation bill. Another Biden Administration claim, for example, here “promise that they would summon “science and truth” to combat the coronavirus pandemic, climate crisis and other challenges.” And that raises the question of course “what specific scientific studies support this claim?” and “who determines what is truth?” What’s the role of “science” compared to other views and interests?

Here’s a link to a Conversation article.

And here’s the abstract.

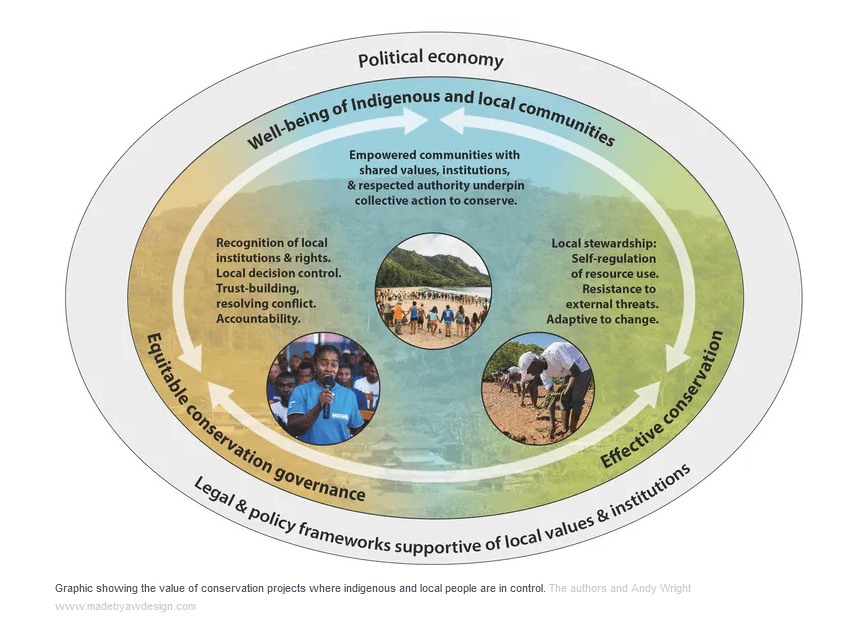

Debate about what proportion of the Earth to protect often overshadows the question of how nature should be conserved and by whom. We present a systematic review and narrative synthesis of 169 publications investigating how different forms of governance influence conservation outcomes, paying particular attention to the role played by Indigenous peoples and local communities. We find a stark contrast between the outcomes produced by externally controlled conservation, and those produced by locally controlled efforts. Crucially, most studies presenting positive outcomes for both well-being and conservation come from cases where Indigenous peoples and local communities play a central role, such as when they have substantial influence over decision making or when local institutions regulating tenure form a recognized part of governance. In contrast, when interventions are controlled by external organizations and involve strategies to change local practices and supersede customary institutions, they tend to result in relatively ineffective conservation at the same time as producing negative social outcomes. Our findings suggest that equitable conservation, which empowers and supports the environmental stewardship of Indigenous peoples and local communities represents the primary pathway to effective long-term conservation of biodiversity, particularly when upheld in wider law and policy. Whether for protected areas in biodiversity hotspots or restoration of highly modified ecosystems, whether involving highly traditional or diverse and dynamic local communities, conservation can become more effective through an increased focus on governance type and quality, and fostering solutions that reinforce the role, capacity, and rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities. We detail how to enact progressive governance transitions through recommendations for conservation policy, with immediate relevance for how to achieve the next decade’s conservation targets under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.

Now there’s at least two interesting things about this paper. It uses “Indigenous and local communities” as a unit. Here within the US, there seems to be great interest in empowering Indigenous communities (at least as long as they agree with certain interests) but perhaps, not so much, local communities. If a community doesn’t want, say, wind turbines, they may be called NIMBY’s. If they do want to produce wood products, they are not in the pockets of extractive interests. And I know that people in local communities disagree among themselves, as do Native Americans. And who wins is ultimately a political/privilege question. Still, I think this would argue for some kind of process that involves all these affected parties directly and transparently.

In the paper, conservation is a bigger idea than what we might think of conservation.. it’s kind of “everything good.”

This review builds on the idea that beyond its environmental objectives, conservation serves to support the rights and well-being of IPLCs. We wish to explore not only the social outcomes of conservation, but also the social inputs, including values, practices, and actions (specifically of IPLCs) that may shape the social and ecological outcomes of conservation. In so doing, we adopt a definition of well-being that is holistic and adaptable to different contexts, encompassing not only material livelihood resources such as income and assets but also health and security as well as subjective social, cultural, psychological, political, and institutional factors (Gough and McGregor 2007). All of the latter elements are increasingly considered as potential social impacts of conservation (Breslow et al. 2016).

(my bold)

It strikes me in focusing on local-led efforts, the Biden Admin 30×30 is following along with these concepts (perhaps “the science”). On the other hand, there appear to be political forces at work to assuage interests who feel quite differently about local processes and involvement (not sure what degree of Tribes), as per re-Monumentization and the Reconciliation bill. It will be interesting to watch how the Administration navigates these tensions through time.