For years we have been told that oil and gas drilling on federal lands is bad because:

1*Federal land is abused for the profits of a few. (corporate profits)

2* Pristine landscapes are industrialized

3* Placement of infrastructure interferes with recreation

4* Bad for wildlife,

5* Roads bad for water quality, also increase human activity

6* Other environmental concerns

7*Methane leakage, chemicals onsite, and finally

8*Usage of oil and gas (not considering substitution from elsewhere)

*******************

If you’ve ever been to a wind installation (whose footprint is much greater and, with proposed solar, is going to be gigantic), you’ll know where I’m going with this.

Some will argue that sacrificing concerns 1-6 are necessary for a low-carbon future. On the other hand, through time, there will be other choices (including in the new IRA) for low-carbon energy such as the nuclear plant being developed in Kemmerer, Wyoming that will use former coal plant workers and existing powerlines.

Anyway, I’m bringing your attention to three stories about this, two current stories one from Wyofile, one from the AP and one from 2019 from the Hill.

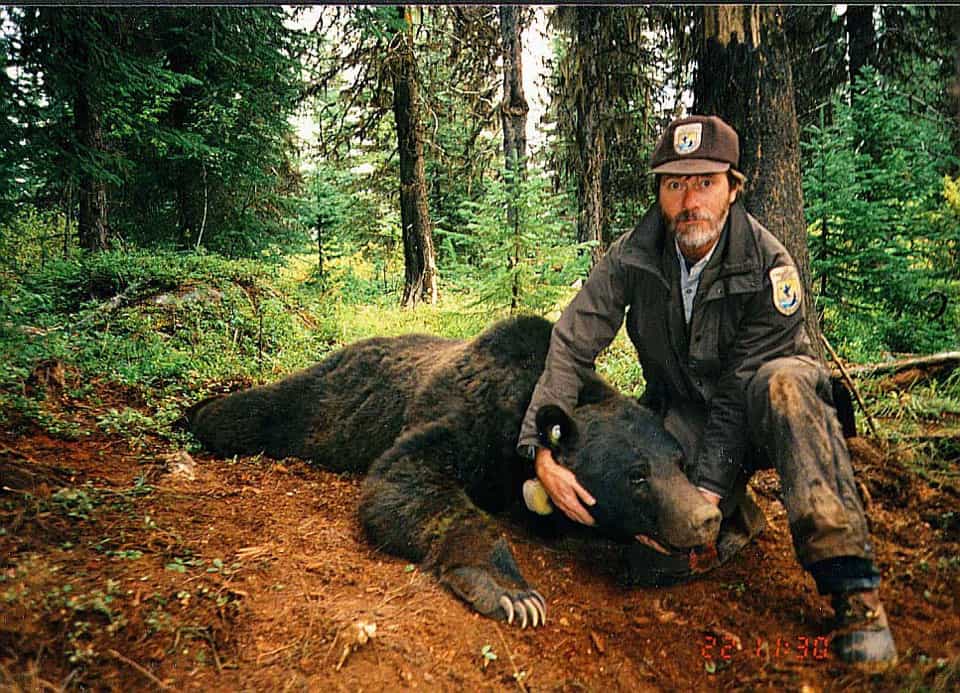

The Wyofile story is an interview with a retired USFWS wildlife biologist now doing resarch for USGS and Conservation Science Global.

The expansion, which energy experts believe may even accelerate further under the Inflation Reduction Act, could pose a serious threat to eagles and other wildlife in certain areas without field-data-driven information to guide avoidance and mitigation strategies, according to Lockhart. …..

This is probably one of the best places, that I know of anyway, for golden eagles in North America,” Lockhart said. “I am a big wind energy advocate and definitely a green energy supporter. But we can’t devastate one really critically important resource for another.”

Maestro has yet to file an official permitting request with the BLM and other permitting authorities. The company didn’t respond to WyoFile inquiries. To move forward, the BLM, which manages more than 80% of the project area, must conduct a full National Environmental Policy Act analysis with public comment.

The Maestro project isn’t the only wind proposal that worries Lockhart.

“I’m equally concerned about the ones that might impact breeding birds and kind of fill in those gaps between the existing wind [energy facilities],” he said.

Another field scientist concerned about modeling over field data (see, it’s not just me).

But Lockhart worries that the vital data from field research is emerging slower than encroaching wind turbines in southern and south-central Wyoming. Federal wildlife managers that can determine where and how wind energy facilities are configured to avoid threatening eagle populations are relying too much on modeling to fill in gaps between actual data, he claims.

“The data is just inadequate for making these [permitting] decisions,” Lockhart said…

Then there are cumulative impacts:

Of particular concern, he said, are proposed wind energy projects that will essentially fill in yet-to-be industrialized areas, such as the Maestro wind energy project in the Shirley Basin. Carlsbad, California-based Maestro Wind LLC proposes to construct up to 327 wind turbines spanning nearly 99,000 acres that straddle Highway 77 here. The project area essentially encompasses the heart of the Shirley Basin’s eagle habitat, according to Lockhart.

Wind energy developers, in the pre-construction federal and state permitting process, typically borrow from existing data on local nesting sites and eagle populations and hire consultants to conduct new surveys in the field. But that information isn’t typically compiled in a way that allows for a comprehensive count or region-wide database that could be used to analyze potential cumulative impacts.

Although the Wyoming Game and Fish Department reviews and comments on wind energy proposals in federal permitting, it doesn’t conduct comprehensive eagle field surveys and mostly defers to federal wildlife authorities, according to Public Information Officer Sara DiRienzo.

“There is a growing concern especially with raptors, such as the golden eagle or the ferruginous hawk, that there may be population impacts, especially when you look at locations that have multiple wind farms,” DiRienzo said. “Understanding the cumulative effects is still ongoing and not conclusive at this time.”

In the mid 90’s there were many Biodiversity workshops, and so I spent much time listening to presentations about endangered birds of various kinds (think owls and murrelets). I had to wonder whether populations go down partially because wildife biologists conduct activities that look like harassment, calling, baiting, trapping and so on. Maybe there are studies on this.

The AP (Matthew Brown) has a lengthy story about eagles and windfarms. I found it in the Colorado Sun. Hopefully it’s not paywalled or is available elsewhere.

The rush to build wind farms to combat climate change is colliding with preservation of one of the U.S. West’s most spectacular predators — the golden eagle — as the species teeters on the edge of decline…

Federal officials won’t divulge how many eagles are reported killed by wind farms, saying it’s sensitive law enforcement information. The recent criminal prosecution of a subsidiary of NextEra Energy, one of the largest U.S. renewable energy providers, offered a glimpse into the problem’s scope.

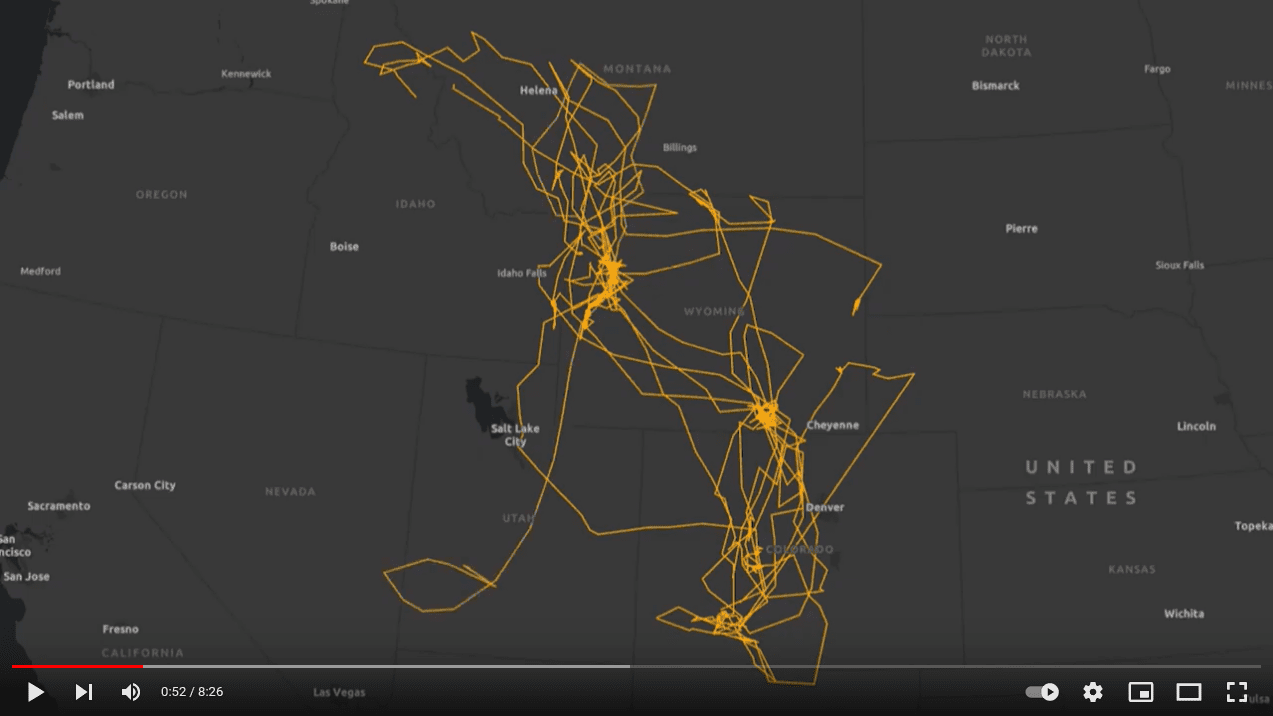

The company pleaded guilty to three counts of violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and was ordered to pay more than $8 million in fines and restitution after killing at least 150 eagles — including more than 100 goldens at wind farms in Wyoming, California, New Mexico, North Dakota, Colorado, Michigan, Arizona and Illinois.

Government officials said the mortality was likely higher because some turbines killed multiple eagles and carcasses are not always found.

Prosecutors said the company’s failure to take steps to protect eagles or to obtain permits to kill the birds gave it an advantage over competitors that did take such steps — even as NextEra and affiliates received hundreds of millions of dollars in federal tax credits for wind power.

The company remained defiant after the plea deal: NextEra President Rebecca Kujawa said bird collisions with turbines were unavoidable accidents that should not be criminalized.

Utilities Duke Energy and PacifiCorp previously pleaded guilty to similar charges in Wyoming. North Carolina-based Duke Energy was sentenced in 2013 to $1 million in fines and restitution and five years probation following deaths of 14 golden eagles and 149 other birds at two of the company’s wind projects.

A year later, Oregon-based PacifiCorp received $2.5 million in fines and five years probation after 38 golden eagle carcasses and 336 other protected birds were discovered at two of its sites.

*******************

We don’t have to go too far back in time, though, to get a different take. From a news piece on The Hill.

Shawn Smallwood, a California ornithologist, told PolitiFact that about 100 eagles die each year due to impacts with wind turbines…

In truth, wind turbine collisions comprise a fraction of human-caused eagle losses,” Obama-era U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Dan Ashe wrote in 2016. “Most result from intentional and accidental poisoning and purposeful shooting. The majority of non-intentional loss occurs when eagles collide with cars or ingest lead shot or bullet fragments in remains and gut piles left by hunters. Others collide with or are electrocuted on power lines.”

I think Ashe’s argument is interesting. If x, y and z contribute to decline of a species, when do we try to shut down x, y, and z, and when do we determine that if the majority of the loss is due to x and y, we aren’t concerned about z. Is the way we think about this inconsistent?

Finally, these articles are about collisions. Noise may also interfere with a variety of bird activities. For example, the highly political dramatized sage grouse..from a BLM document:

Recent research has demonstrated that noise from natural gas development negatively impacts sagegrouse abundance, stress levels and behaviors (Blickley et al. 2012; Blickley & Patricelli 2012; Blickley et al. In review). Other types of anthropogenic noise sources (e.g. infrastructure from oil, geothermal, mining and wind development, off-road vehicles, highways and urbanization) are similar to gas-development noise and thus the response by sage-grouse is likely to be similar. These resultssuggest that effective management of the natural soundscape is critical to the conservation and protection of sage-grouse.