REGULATIONS

On June 22, the Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service proposed (for public comment by August 23) a new set of regulations for administering the Endangered Species Act, which for the most part cancelled many of the changes adopted by the Trump Administration. This follows litigation that resulted in the Trump rules being kept in place pending this action by the Biden Administration. The changes are in three rules governing these main topics:

- Interagency consultations under ESA section 7, including clarifying the distinction between the environmental baseline and effects of the action

- Procedures and criteria for listing, reclassifying, delisting, and designating critical habitat for species under ESA section 4, including loosening criteria for designating unoccupied habitat, validating the role of long-term effects such as climate change, and removing economic considerations from this scientific process

- Reinstatement of USFWS’s blanket ESA section 4(d) rule which, prior to its repeal in 2019, extended the take prohibitions of ESA section 9 to all species. listed as threatened under the statute unless USFWS issued a species-specific rule

While those who liked the Trump version would be expected to criticize all of this, the conservation organizations are not entirely happy that some of the Trump changes have been retained. A couple of key ones noted by the Sierra Club include:

“One such regulation severely undercuts critical habitat protections. The policy says a development project must affect critical habitat “as a whole” before alternative projects are considered. This would protect a species with a small range because a major infrastructure project would likely destroy its entire area, and thus it would be hard to approve such development. Not so for species with large ranges, like northern spotted owls and gray wolves. There would never be an instance where habitat was destroyed as a whole for a species whose range includes hundreds, thousands, or even millions of acres.”

“Another missed opportunity, conservationists say, was the chance to update the definition of “environmental baseline,” a term used to describe the habitat of a listed species before federal agencies begin a project. Agencies are supposed to evaluate whether their activities jeopardize a species’ survival and recovery. The Biden administration decided to keep the 2019 rule that allows officials to overlook the cumulative effects of past decisions for ongoing projects. Dams in the Pacific Northwest, for example, have pushed salmon and trout runs to the brink of extinction. When a federal agency is looking to extend a dam’s operating license or approve a new dam operating plan, its consultation with the wildlife agency shouldn’t ignore those past effects on the species’ biological condition.” (For land management agencies, this might apply to something like roads.)

On July 3, the Fish and Wildlife Service adopted a final section 10(j) rule that would allow it to establish experimental populations of endangered species in places outside of their normal historical range. This is primarily in response to changes in species’ habitat resulting from climate change:

“Through this rule change we are adjusting our regulatory authority to allow us to adequately respond to these potential scenarios in circumstances where it may not be possible to recover a species within its historical range because of loss or alteration of some or all its suitable habitat,”

LITIGATION

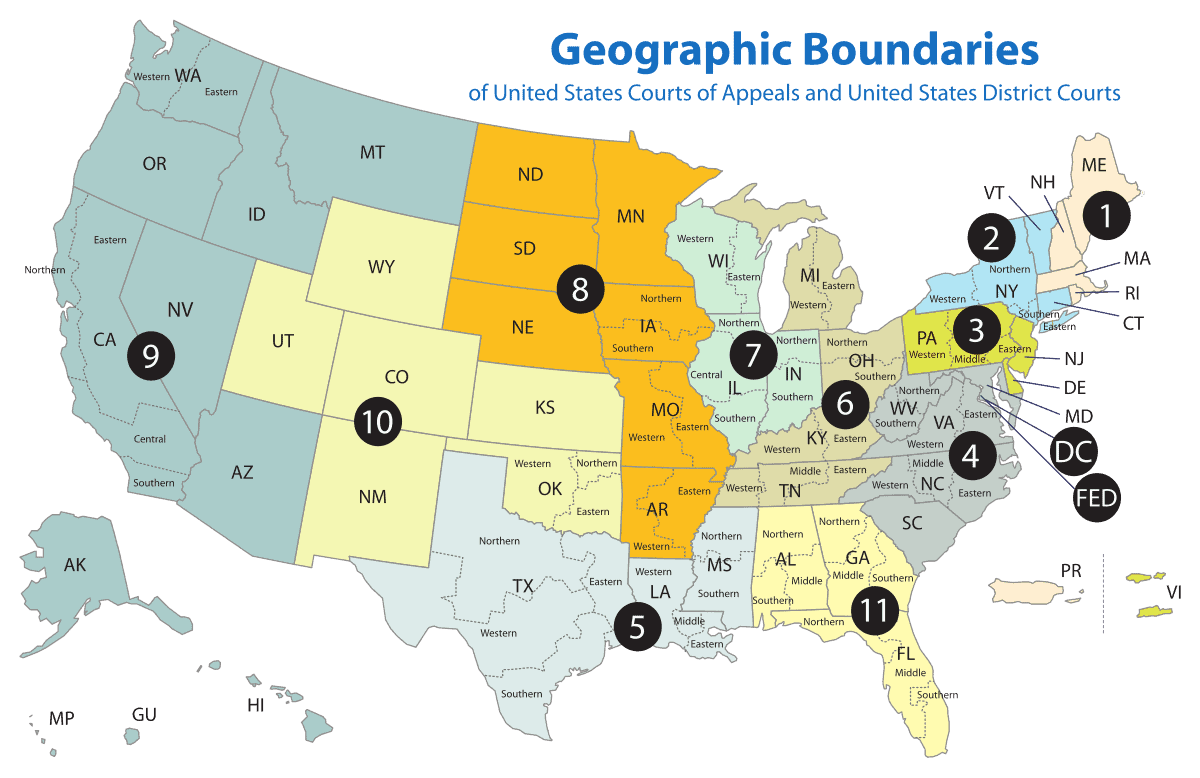

Court decision in Maine Lobstermen’s Association v. National Marine Fishery Service (D.C. Cir.)

On June 16, the circuit court reversed a district court decision and invalidated a regulation issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service to protect Atlantic right whales from lobster and crab fishing activities. The case is viewed as significant because it discusses and dismisses the use of the “precautionary principle” where there is scientific uncertainty under the Endangered Species Act.

NMFS consulted with itself on the regulation to determine if jeopardy would be likely. In its Biological Opinion, NMFS concluded that federal fisheries entangle more than 9% of right whales each year. According to the court, to reach this estimate, the Service put aside the data on confirmed entanglements and relied instead upon a “scarring analysis” from a 2019 study, noting “This approach provides the benefit of the doubt to the species and a more conservative estimate of total right whale entanglements.” NMFS stated that “uncertainty is resolved in favor of the species” and that it generally “select[s] the value that would lead to conclusions of higher, rather than lower, risk to the endangered species.” To defend its use of the worst-case assumptions, the agency pointed to a line in a House Conference Report for the 1979 amendments to Section 7 of the ESA, which stated that “this language continues to give the benefit of the doubt to the species.” In its consulting role, NMFS concluded that the regulation would not jeopardize the species. In adopting the regulation, NMFS acknowledged that its “model outputs very likely overestimate the likelihood of a declining population.”

The court declined to give deference to the agency, and held the BiOp was arbitrary because in the administrative record NMFS had erroneously claimed that its position was required by the ESA’s legislative history, and because its current “policy” on resolving uncertainty using the precautionary principle conflicted with its prior (opposite, under the Trump Administration) position. In addition, the court stated:

“Statutory text and structure do not authorize the Service to “generally select the value that would lead to conclusions of higher, rather than lower, risk to endangered or threatened species” whenever it faces a plausible range of values or competing analytical approaches. The statute is focused upon “likely” outcomes, not worst-case scenarios. It requires the Service to use the best available scientific data, not the most pessimistic…

If brute uncertainty does make it impossible for the Service to make a reasoned prediction, however, the interpretive rules supply a ready answer: The Service lacks a clear and substantial basis for predicting an effect is reasonably certain to occur, and so, the effect must be disregarded in evaluating the agency action.”

However, the court left the regulation in place, concluding that NMFS might be able to justify it on remand. (Perhaps meaning, “if they say it in a different way.” It may also be possible for the consulting agencies to interpret a study that uses the precautionary principle as the best available science for predicting likely outcomes.) Here is another summary of the case.

“Greenwire,” in its “occasional series” discusses the role of litigation in implementing the Endangered Species Act. Some highlights:

During President Ronald Reagan’s first three years, 22 species were listed as threatened or endangered. By contrast, 100 species got protections in the Carter administration’s first three years. In response, a frustrated Congress in 1982 amended the law to add deadline teeth.

A 2017 Government Accountability Office study found that plaintiffs filed 141 such ESA missed-deadline suits between fiscal 2005 and 2015.

“The Fish and Wildlife Service knows the workload, and it refuses to ask for enough money to get the work done,” Suckling (Center for Biological Diversity) said, “and then when it doesn’t get the work done, it goes to the judge and says, ‘Your Honor, I don’t have enough money.’”

“Of our total revenue in a given year, only about 5 percent comes from legal returns,” Suckling said. “It’s really just not that much money, [and] settlements are good for everybody.”

“We could avoid having to fully litigate cases and use scarce resources to do so if the agency would agree to settle cases more,” said Larris of WildEarth Guardians, “but they much more often decline to settle.”

In what’s still one of the most comprehensive studies of its kind, Biber and co-author Berry Brosi, a biologist now at the University of Washington, assessed the role played by petitions and litigation with hundreds of species. They concluded, in a 2010 issue of the UCLA Law Review, that species listed as a result of a petition or litigation faced greater threats than species listed on the agency’s initiative. Biber said he believes the 2010 conclusions remain valid, saying that overall, petitions and litigation “are beneficial [in] ensuring that the species most at threat are protected.”

Former FWS Director Dan Ashe, who oversaw the agency during the Obama administration and now is the president and CEO of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, assessed that “litigation overall has been beneficial” in sustaining a focus on protecting species.