It’s Valentine’s Day, and I would like to give a special Smokey Wire Valentine to Sara C., who answered my questions on the PM 2.5 Rule in a very clear and concise way. In case you didn’t read it in the comments, here are her answers. As hard as our regular contributors work, we can’t keep up with everything of interest, and so that’s why we all appreciate folks who step up with their knowledge. Here’s what Sara had to say in this comment link.

It’s Valentine’s Day, and I would like to give a special Smokey Wire Valentine to Sara C., who answered my questions on the PM 2.5 Rule in a very clear and concise way. In case you didn’t read it in the comments, here are her answers. As hard as our regular contributors work, we can’t keep up with everything of interest, and so that’s why we all appreciate folks who step up with their knowledge. Here’s what Sara had to say in this comment link.

Hi all – I’m an environmental attorney and work with a number of prescribed fire and cultural burning advocates on these issues. Here are the brief answers to Sharon’s questions:

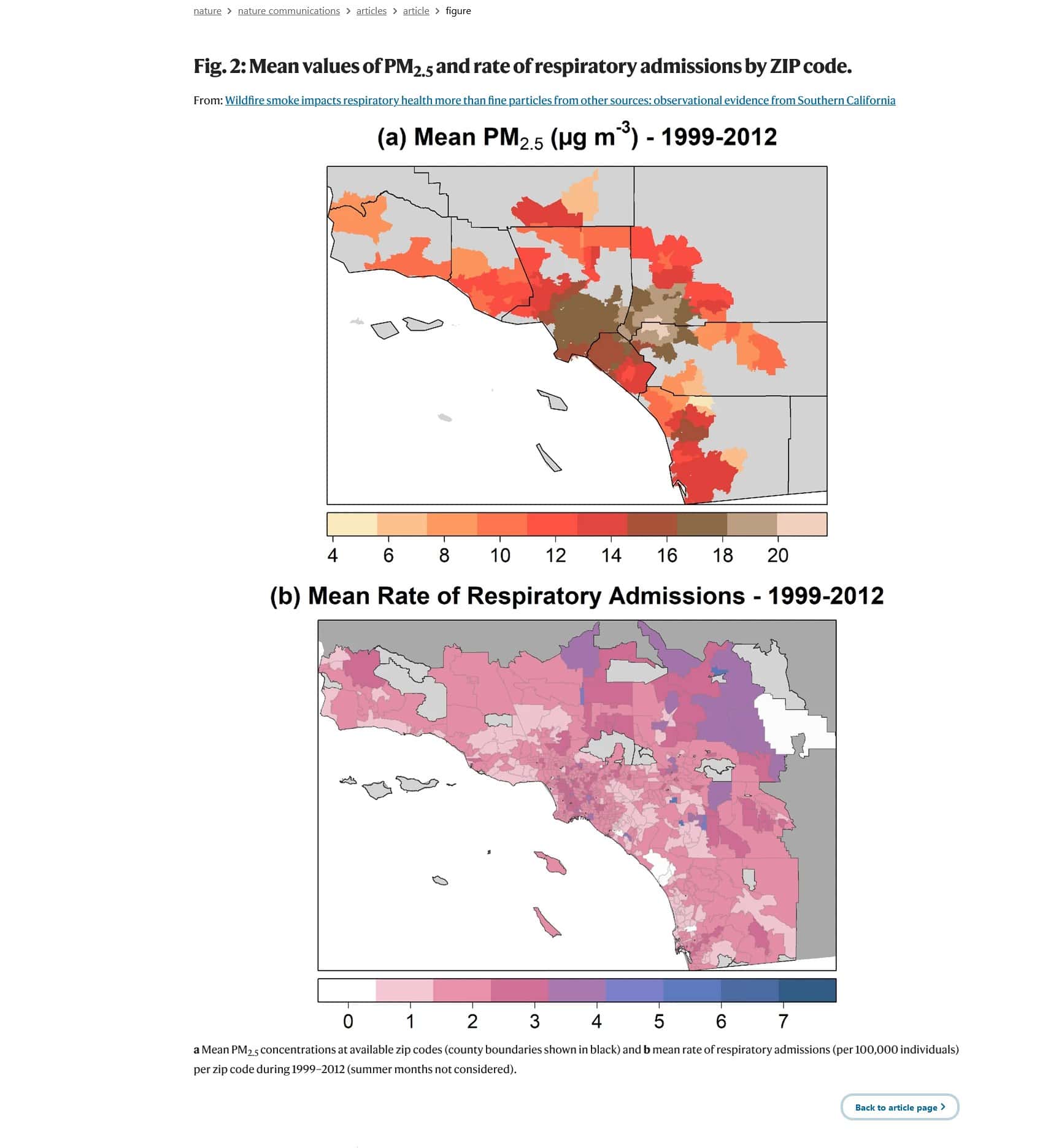

(1) What new things do wildfire folks have to do (if anything)? The Clean Air Act puts the onus on state air pollution control agencies, not wildfire folks. With a stricter standard, more air basin will fall into “nonattainment” for PM2.5 (from both wildfire and other pollution) – these new designations will be made by February 2026. For those areas in nonattainment, the air agencies/states will have to come up with “state implementation plans” to demonstrate to EPA how they’ll come back into compliance. Those “SIPs” will be due in August 2027.

The wrinkle is that wildfire smoke can also be “excluded” from consideration using a process called the Exceptional Events Rule. It’s still the air agencies that are responsible for preparing Exceptional Events “demonstrations”, but they may look to wildfire folks for help with data, etc. Once “excluded,” then the wildfire smoke doesn’t count for regulatory purposes.

(2) What new things do prescribed fire folks have to do (if anything)? It depends whether your state falls out of attainment, and if so, how your state chooses to come back into attainment through the SIP. Some states may choose to make permitting for prescribed fire more difficult in response, or may require prescribed fire practitioners help with exceptional events demonstrations if they get permits. For now, prescribed fire practitioners should be paying attention to how their states are going to respond, and work to make sure that smoke from prescribed fire isn’t the source that’s targeted for curtailment.

(3) Does EPA think “hey since we have wildfires (this year? over time? future using computer models?) and prescribed fire, and then we have to ratchet all other activities further down (e.g. industry, cars, etc.)? Under the Clean Air Act, EPA leaves the targeting of specific sources to the states. Some states may want to use it as a reason to ratchet down other activities, some states may chose to ratchet down prescribed fire instead. There are some unique incentives though, given that wildland fire and prescribed fire can be excluded via an exceptional events demonstration, and traditional sources of pollution cannot.

(4) What does it mean in practice to deal with Exceptional Events? What is a demonstration? The Exceptional Events Rule is the part of the clean air act that allows states to exclude certain emissions. Generally speaking, the CAA regulates the “ambient” air quality — no matter the source, states can be on the hook exceedances of the standards. But the CAA recognizes that states sometimes have no control over a particular source, and therefore shouldn’t be penalized for it – the prototypical examples are dust storms and wildfire. In 2016, the EPA revised the regulations for exceptional events to make clear that prescribed fires might also qualify, but until the demonstration above, this path had never been used. The main reason is that exceptional events demonstrations — i.e., the name for the pathway to get EPA to agree to exclude the data — are technically complicated and resource intensive. The one referenced above took experienced EPA staffers 3 months. So instead of agreeing to let a prescribed fire happen and then preparing to file a difficult and uncertain exceptional events demonstration, air regulators may simply deny or condition prescribed fire permits so no exceedance is likely.

(Note, I edited the last sentence a bit, I’m hoping that’s what she meant and that she will comment if it’s not.)

Anyone else who would like to add information or links, please add below.

Commenter Shaun recently pointed out that many of the policy changes he’s seen, for the last little while (he mentioned 38 years), have tended to centralize decisions. Of course, there has always been a partnership between the Feds and States with regard to the Clean Air Act. What is also interesting to me to watch is Agency Encroachment in the form of EPA seeming to get regulatory tentacles further into everything else (energy production, WOTUS, plant genetics, fire retardant) while at the same time saying they don’t have enough budget or employees. It would indeed be a paradox if EPA is very worried about climate change, but also makes more difficult our efforts to protect ourselves from those same negative impacts. Anyway, I think watching new policies as to what more work is involved, and who makes the decisions, will be a worthwhile exercise.