A former Forest Service backcountry specialist talks about ecological integrity and increasing human recreation activities, and tries to answer the question of “what is sustainable recreation?” The 2012 Planning Rule requires plan components “to provide for: (i) Sustainable recreation; including recreation settings, opportunities, and access; and scenic character.”

What is “Sustainable Recreation”? The Forest Service defines it as “the set of recreation settings and opportunities in the National Forest System that is ecologically, economically, and socially sustainable for present and future generations.”

Here’s how it’s done:

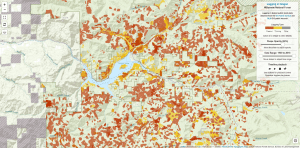

The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum can be used in forest planning to define a desired condition for management within each zone. Indicators and standards are meant to define the tipping point beyond which management action must be taken.If the standard for a backcountry area (called “semi-primitive non-motorized” in ROS jargon) is that no more than six other parties are encountered on a typical day, when the encounter rate exceeds that number some action is supposed to take place to return to the desired condition.It’s a neat framework, but doesn’t always play out as intended on the ground. ROS doesn’t differentiate between a semi-primitive area in the back yard of a town like Jackson or Bozeman and one that’s two hours away.

The usual sequence of remedial actions begins with non-intrusive measures like visitor education. If the problem isn’t solved, additional actions are considered.The Bridger-Teton forest plan is typical in its prescribed sequence of actions, this excerpt taken from its direction on wilderness. The following recreational strategies should be used, listed in descending order of preference:First Action – Efforts are directed towards information and education programs and correction of visible resource damage.Second Action – If the first action is unsuccessful, restrict activities by regulation (for example, set a minimum distance between a lakeshore and where people can camp).Third Action – If the first and second actions fail, restrict numbers of visitors.Fourth Action – If first, second, and third actions are not successful, a zone can be closed to all recreation use until the area is rehabilitated and restored to natural conditions.In my experience, outside of designated wilderness and other special areas where specific laws apply, the Forest Service keeps circling around the first action, which isn’t a bad strategy given the continuing need for it in communities where resident turnover is high. It’s an ongoing need regardless of the often unmet requirement to step up restrictions. But restrictions trigger blowback, as when the Shasta-Trinity National Forest tried to set encounter limits for the wilderness that includes Mt. Shasta.People basically said they don’t care if it’s crowded—they just want to reach the summit, and a judge agreed with them. On the other hand, those who float the Selway River are happy to wait until they get a launch day shared by no one else. Since everyone is going the same direction at about the same speed, everyone can experience a bit of peace and quiet. So the application of sustainable recreation standards depends on who is using the forest and what they will accept.

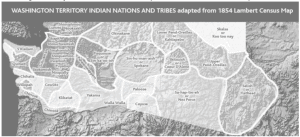

User-built trails and roads are often the opposite of sustainable. They develop incrementally and aren’t designed with soil type, grades and curve radii in mind, or the needs of resident wildlife. The trail system after adoption by the Forest Service usually gets reworked so it doesn’t turn into deep ruts or wash into the creek, but where is the analysis that determines that the trail location is right in the first place? The trail itself becomes more sustainable, but where do the grouse and elk and owls go?

While the planning rule makes clear that ecological integrity underlies compatible uses in a national forest, the ecological, economical, and social sustainability have since been referred to as a three-legged stool, with all three legs of equal importance.

“Plans will guide management of NFS lands so that they ARE ecologically sustainable and CONTRIBUTE TO social and economic sustainability; CONSIST OF ecosystems and watersheds with ecological integrity and diverse plant and animal communities; and HAVE THE CAPACITY TO PROVIDE people and communities with ecosystem services and multiple uses that provide a range of social, economic, and ecological benefits for the present and into the future.