As we discuss topics on The Smokey Wire, sometimes there are echoes of the Timber Wars. The idea being that forest industry is bad and forests should be left alone. But that is not so true in dry forests, because there are millions of tons of wood to be removed fore restoration and/or fuel treatment; either before or instead of prescribed fire; and across the West, thousands of landowners other than the feds who would like to do something useful with the wood they remove, and have those projects cost less, plus not have to burn piles and release the carbon directly.

Perhaps the peaceful settlement of the Timber Wars is that (1) ENGOs and others agree on what needs to be removed for restoration/fuel treatment purposes, then, (2) industries that utilize that material can become partners instead of enemies.

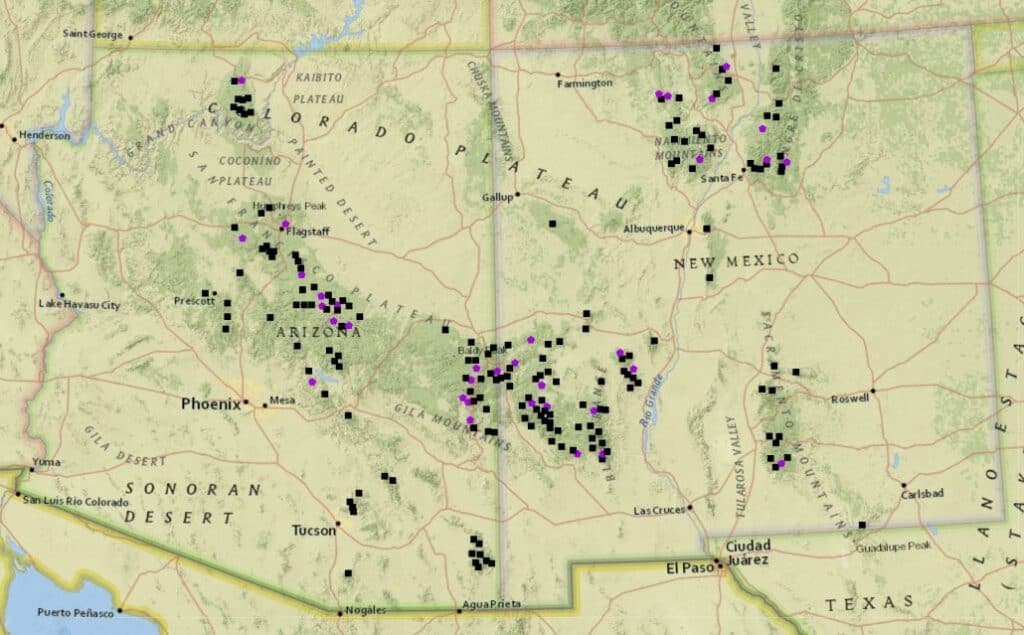

A problem has been, though, for industry to invest in facilities and equipment, they need long-term contracts. Which has always been a stumbling block.. at least until 4FRI broke down that wall. In 4FRI, everything seems to be lined up that different folks in different places have found to be problems…

- Agreement with ENGO’s on tree removal do’s and don’ts.

- Large EIS

- Long-term contracting approval

- Some industry capacity (timber and biomass)

- Political support at all conceivable scales

- All kinds of research support by NAU, including this chip’n’ship program. Thinking outside the container…

- A GTR.. after the success of the Sierra GTR in California, I’ve heard folks say “we really need a GTR.” (this is a General Technical Report generally done by FS research scientists and others, that round up the relevant scientific information).

- And, I bet, support from the Region and the WO of the FS.

- Plus partners of all imaginable kinds and a collaborative spirit.

The 4FRI folks- FS and a whole host of partners- are pioneers in the world of forest landscape scale restoration. And yet, with all these advantages, they keep running into (and ultimately surmounting, not to forget) problems. All of them must get weary of being at the forefront, and I’d hope that we in their wake can take a moment to appreciate their work and encourage them. The most recent example of a challenge is the recent contract cancellation of the Phase II RFP. This is the first of two posts, and in this post I’ll focus on the Forest answers to my questions. My questions are in italics, and the Forest answers are in bold.

- Given all your support and collaborative success, why did this go wrong?

Forest answer:

This effort was unprecedented; the FS has never done a contract like this and never attempted a stewardship contract of this magnitude before, which would be for performance on over half a million acres over 20 years and designed to significantly enhance industry capacity.

During the procurement process, we changed the requirement and amended the solicitation multiple times to add certainty and/or reduce risk to offerors. Despite that, we concluded that significant risks persist which compromise the likelihood of successful performance over 20 years. We have also concluded that issuing any additional amendments at this time would warrant issuing a new solicitation and re-advertisement.

(2) Your press release gave some information but perhaps you could go into more detail… you think you need to change X so that folks will be more likely to bid on it?

We need to re-assess the requirements so that any new solicitation issued would better address all risks to offerors and the Government, including financial and investment risks including:

- Economic Price Adjustment requirements;

- Acreage and volume of material to be offered;

- Biomass treatment requirements;

- Road maintenance requirements; and

- Cancellation ceiling.

Until these risks associated are better addressed, there is no reason to expect an outcome from the current RFP process that will meet the needs of the Forest Service or Industry.

(3) Are there anything you would like to add or clarify from the newspaper articles? (they are in the next post)

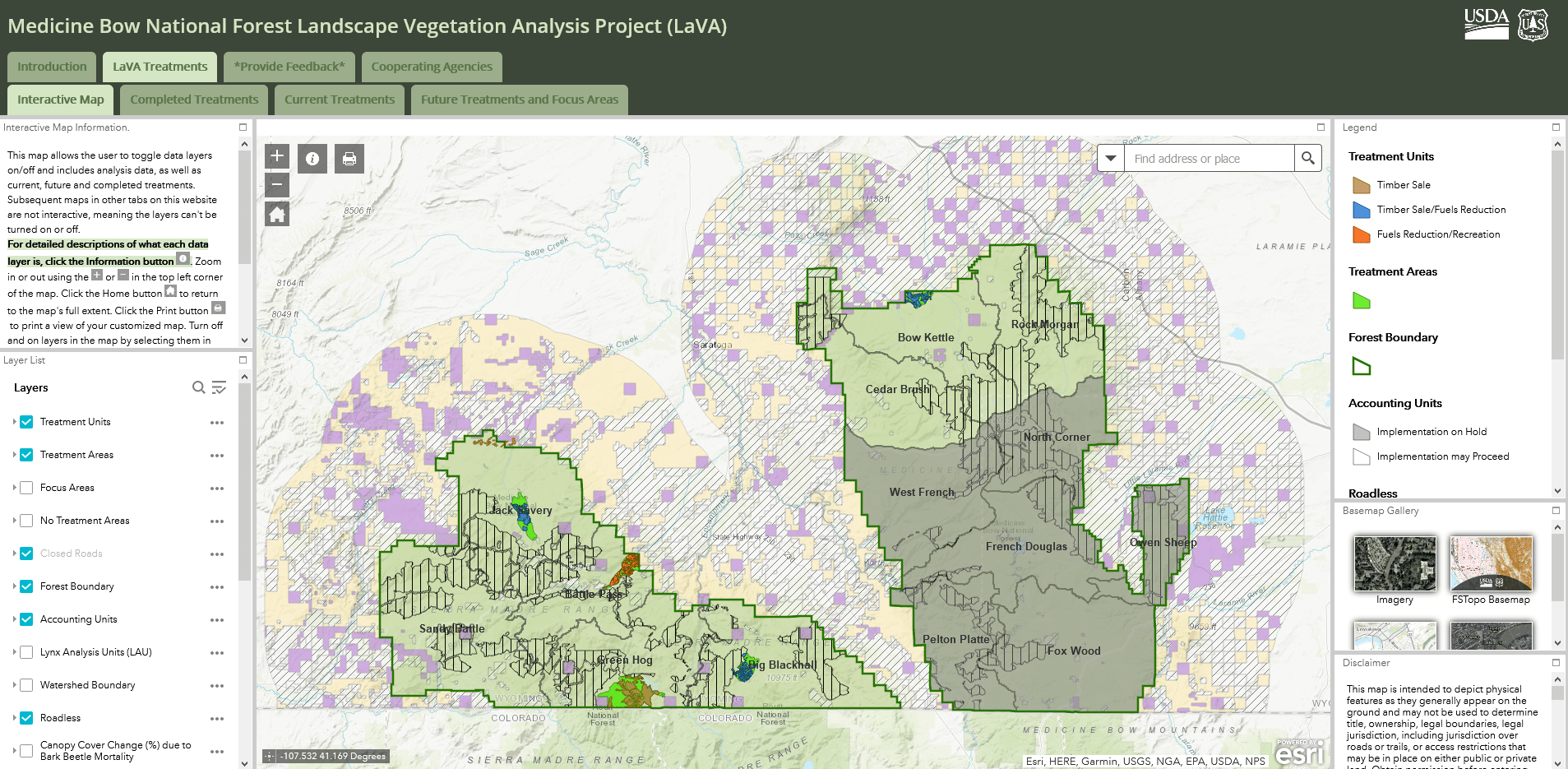

First, the cancellation of the 4FRI Phase 2 RFP does not affect any ongoing forest restoration or fuels reduction work. We are continuing to get work done across the 4FRI landscape including critical fire risk-reduction projects in key municipal watersheds including C.C. Cragin, Flagstaff Watershed Protection Project (FWPP), and Bill Williams Mountain. We have several Good Neighbor Authority agreements (GNA) in place between the Forest Service and the State of Arizona to get this work done. We also have several stewardship agreements in place for forest restoration with key partners including the National Forest Foundation, National Wild Turkey Federation, and the Nature Conservancy.

Second, the goals of the 4FRI project have not changed due to the RFP cancellation. We are deeply invested in landscape restoration and our intention is to work with our partners together on a new RFP as soon as possible. We are actively working with our partners, stakeholders, industry, and elected officials to ensure success when implementing future contracts or agreements. Starting with the 4FRI Stakeholders Group (SHG) and continuing with the Natural Resource Working Group (NRWG) we have discussed what we’ve all learned and how we can integrate it for success. We have already received clear feedback from our partners and industry to move forward rapidly and we will. In the next few weeks, there will be an Industry Roundtable, SHG meetings, and many discussions leading to a new proposal. The Forest Service is grateful for this support.