Durango Herald file

Southwest Colorado could be the focal point of a pilot project that seeks to make strides in improving forest health in the face of increasing dangers from wildfire, disease and beetle kill.

Earlier this year, the National Wild Turkey Federation approached the U.S. Forest Service to talk about the challenges in forest management that impede fast-paced and large-scale landscape restoration.

In the past, the Forest Service has tried to spread its budget for forest health projects evenly across a landscape, said Kara Chadwick, supervisor for the San Juan National Forest.

“We’ve been struggling with this as an agency for a while,” Chadwick said. “We get a little bit done everywhere.”

But forest officials started to wonder: What if you directed all your resources, in terms of time and money, to one or two places to accomplish critical improvements, rather than make slow progress in multiple places.

“The idea is to focus in one place, and once you’ve achieved that change on the landscape, move to another,” Chadwick said.

The project is called the Rocky Mountain Restoration Initiative, or RMRI.

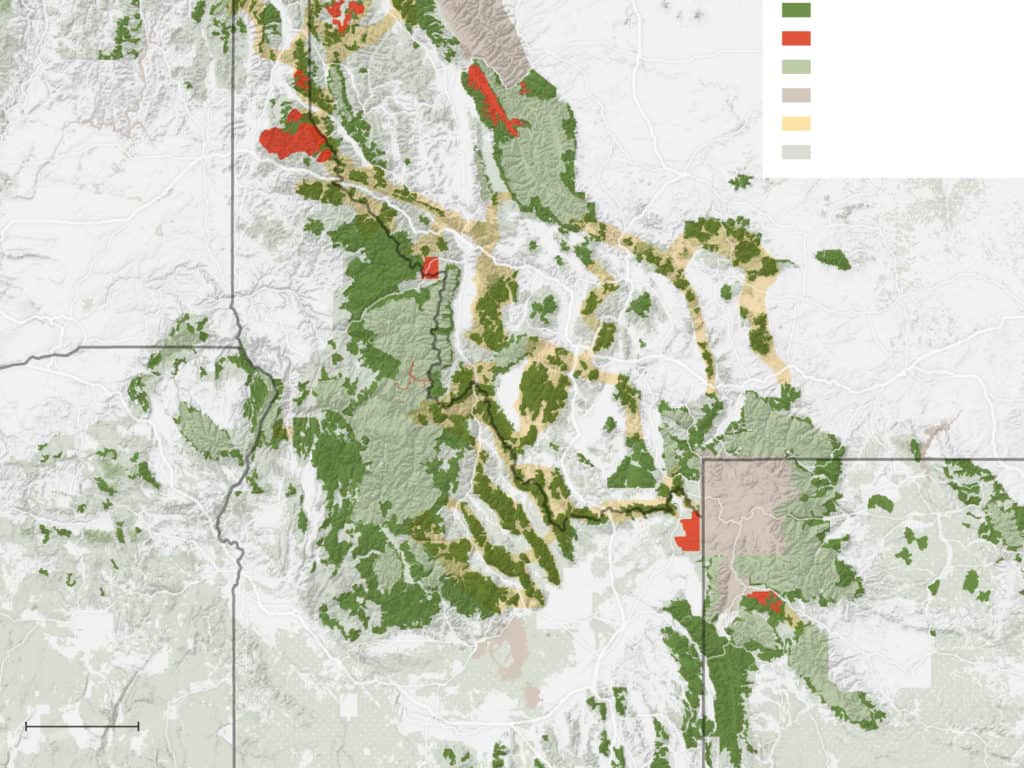

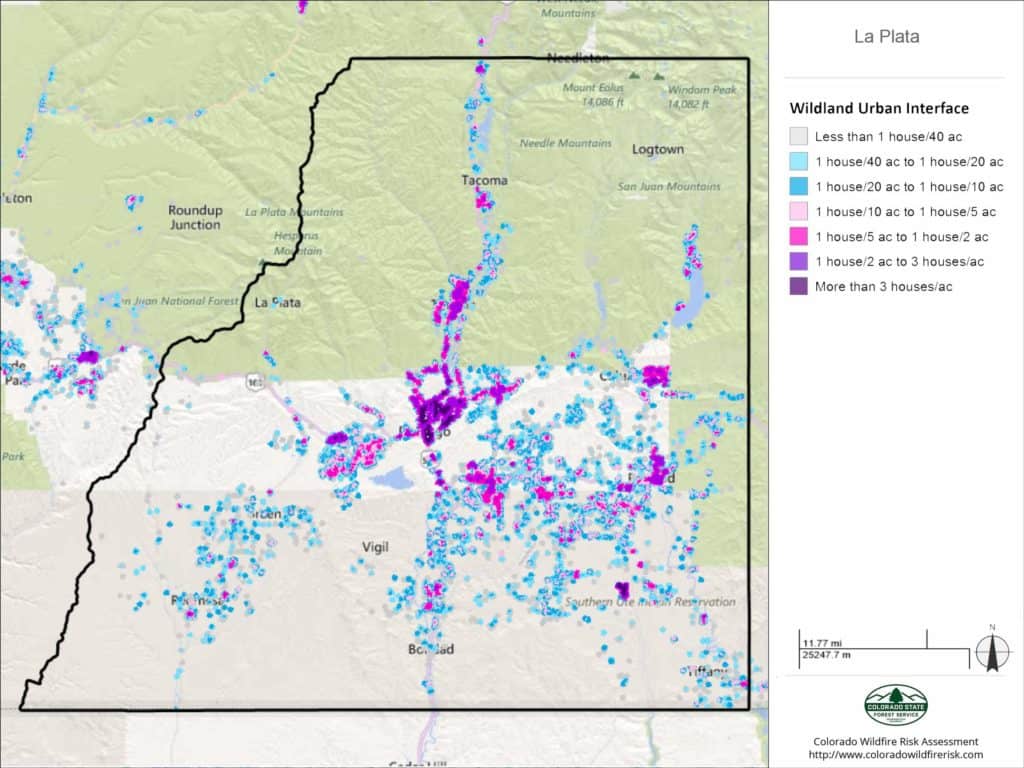

Colorado was chosen as the state to pilot the project for several reasons: It’s home to the headwaters of four major river systems; nearly 3 million people live in the wildland-urban interface; and outdoor recreation is a big part of the state’s economy, to name a few.

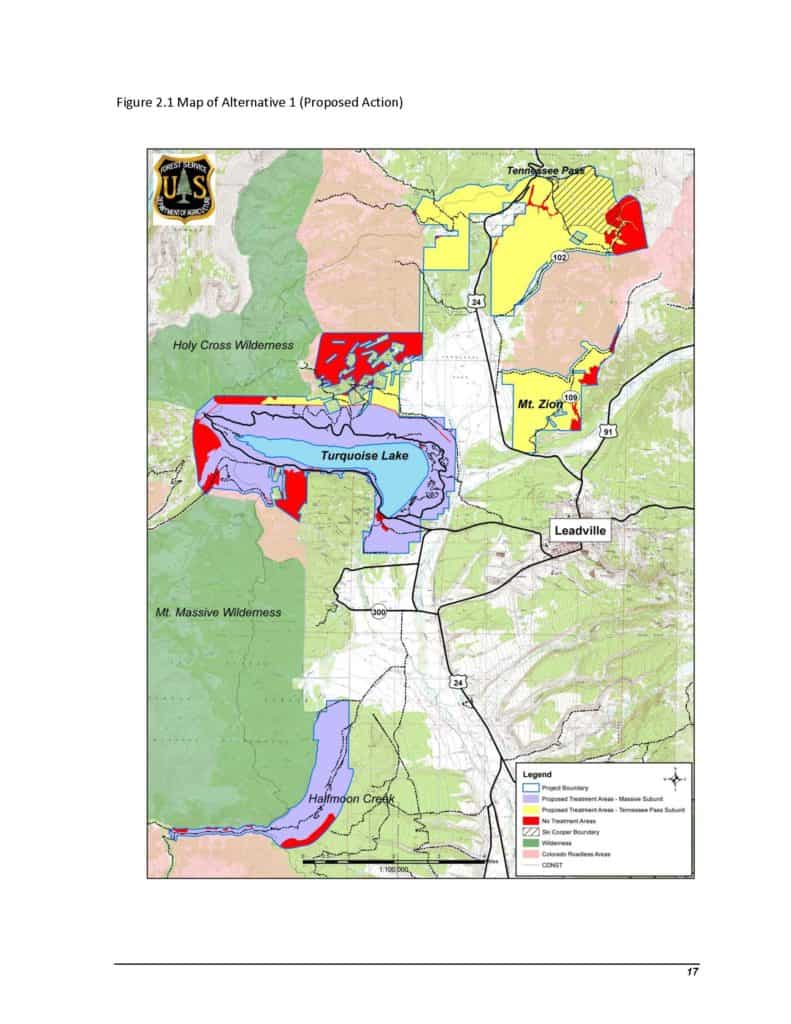

Within the state, three regions are being considered to test the project: the central Front Range, the Interstate 70 corridor and Southwest Colorado.

…

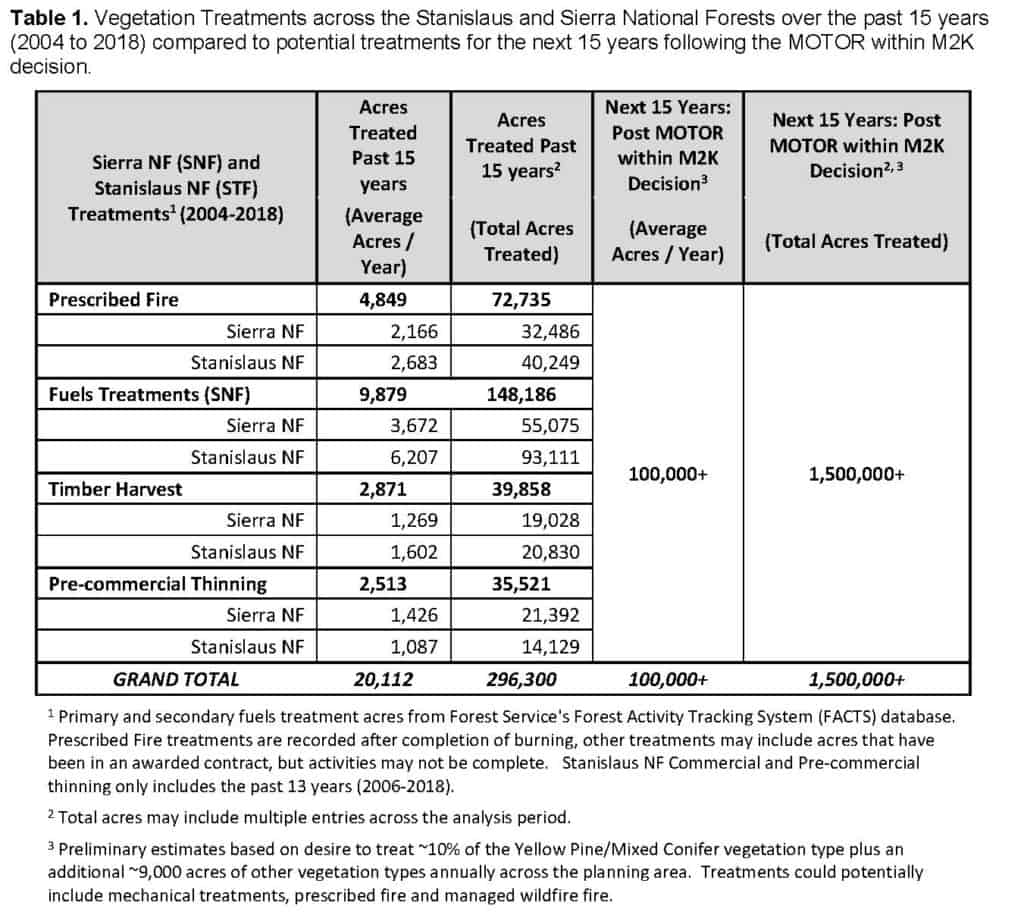

The idea, Chadwick said, is to work across all boundaries – federal, state and private lands – to make “transformative change” on the landscape through projects like forest thinning, prescribed burns and boosting logging operations.

Chadwick said areas around Durango, west along the U.S. Highway 160 corridor and up to Dolores could be areas of particular focus.

In La Plata County, for instance, about 53,800 people, or 96.9% of the total population, live in the wildland-urban interface.

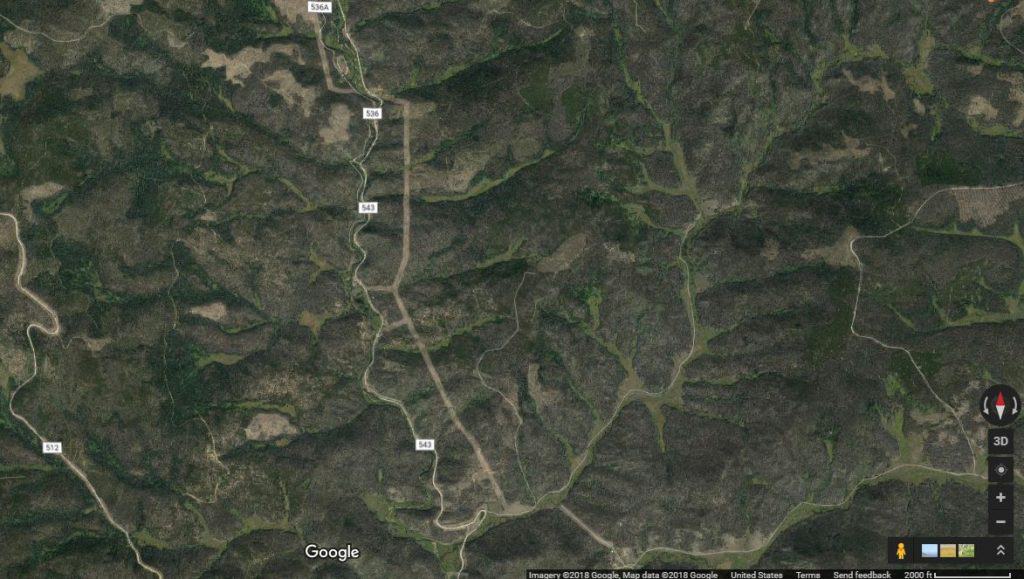

Another major part of the program is to improve and protect watersheds. Mike Preston with the Dolores Water Conservancy District said the pilot project could also be used to thin badly overgrown ponderosa forests in the Dolores River watershed.

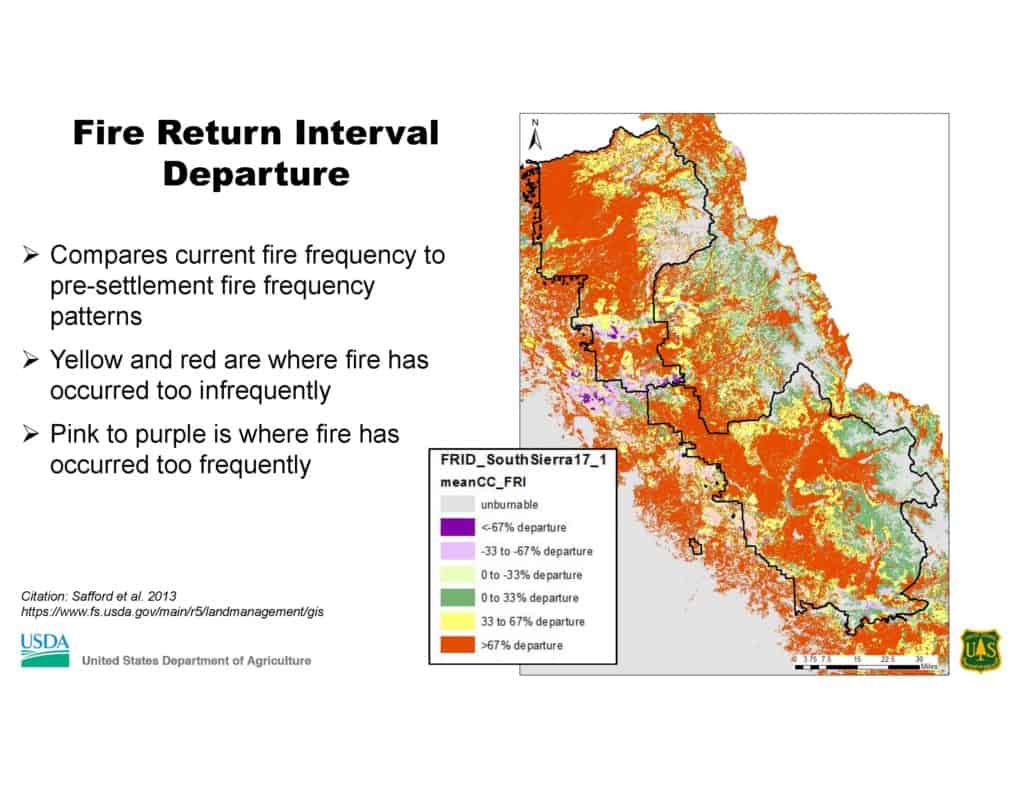

Past forest management practices have created too-dense tree stands, which can exacerbate issues with wildfire and beetle spread, as well as suck up an inordinate amount of water, Preston said. Encouraging prescribed burns and forest thinning through harvest sales could help with all these issues, he said.

“The problem is, with limited resources available to advance forest health, the pattern has been to spread resources across the entire forest,” he said. “With this project, we’re attempting to concentrate on one or two projects and see what can be accomplished moving more aggressively and timely.”

Chadwick said the hope is to have a final decision on the pilot project by this December. Any work on the landscape would have to go through the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires a study on the environmental impacts of a particular project.

“I think we can get a lot of really good work done, and in the process, build better relationships across the landscape,” she said.