Thanks to Susan Britting of Sierra Forest Legacy for sharing this Novermber 2020 Forest Management Statement signed by a broad coalition that included the following groups:

California Native Plant Society ▪ California Wilderness Coalition ▪ Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center ▪ Defenders of Wildlife ▪ The Fire Restoration Group ▪ The Nature Conservancy, CA Chapter ▪ Sierra Business ▪ Council Sierra Forest Legacy ▪ The Watershed Center

Statement on Forest Management

California forest conditions

• Well managed forests provide many critical benefits for nature and people including clean air, clean water, wildlife habitat, carbon storage, recreation and more.

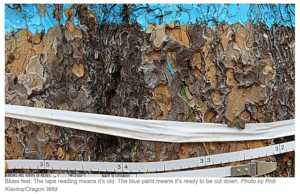

• Current conditions in many fire-prone forests of the Sierra Nevada and elsewhere in California are degraded and not healthy due to past logging practices, fire suppression, drought, and climate change. From the perspective of forest health and resilience, there are too few large trees, too many small trees, and an excess of “surface and ladder fuels” that significantly increase the risk of high-severity wildfire.

• California is experiencing high-severity wildfire in larger landscapes and at larger scales than is desirable from an ecological perspective.

• Threats to forest communities from high-severity wildfire are increasing and need to be addressed.

• There is an urgent need to restore more natural forest structure and reintroduce beneficial fire so that forests continue to provide important ecosystem services and pose less of a threat to

life and property.An integrated solution: communities and landscapes

• We support an integrated strategy to reduce the risk of high-severity wildfire near communities and across the forest landscape, including public and private lands.

• The strategy needs to utilize all tools in the toolbox: ecologically based forest thinning, prescribed fire, managed fire, cultural burning, working forest conservation easements, defensible space, home hardening, and emergency response.

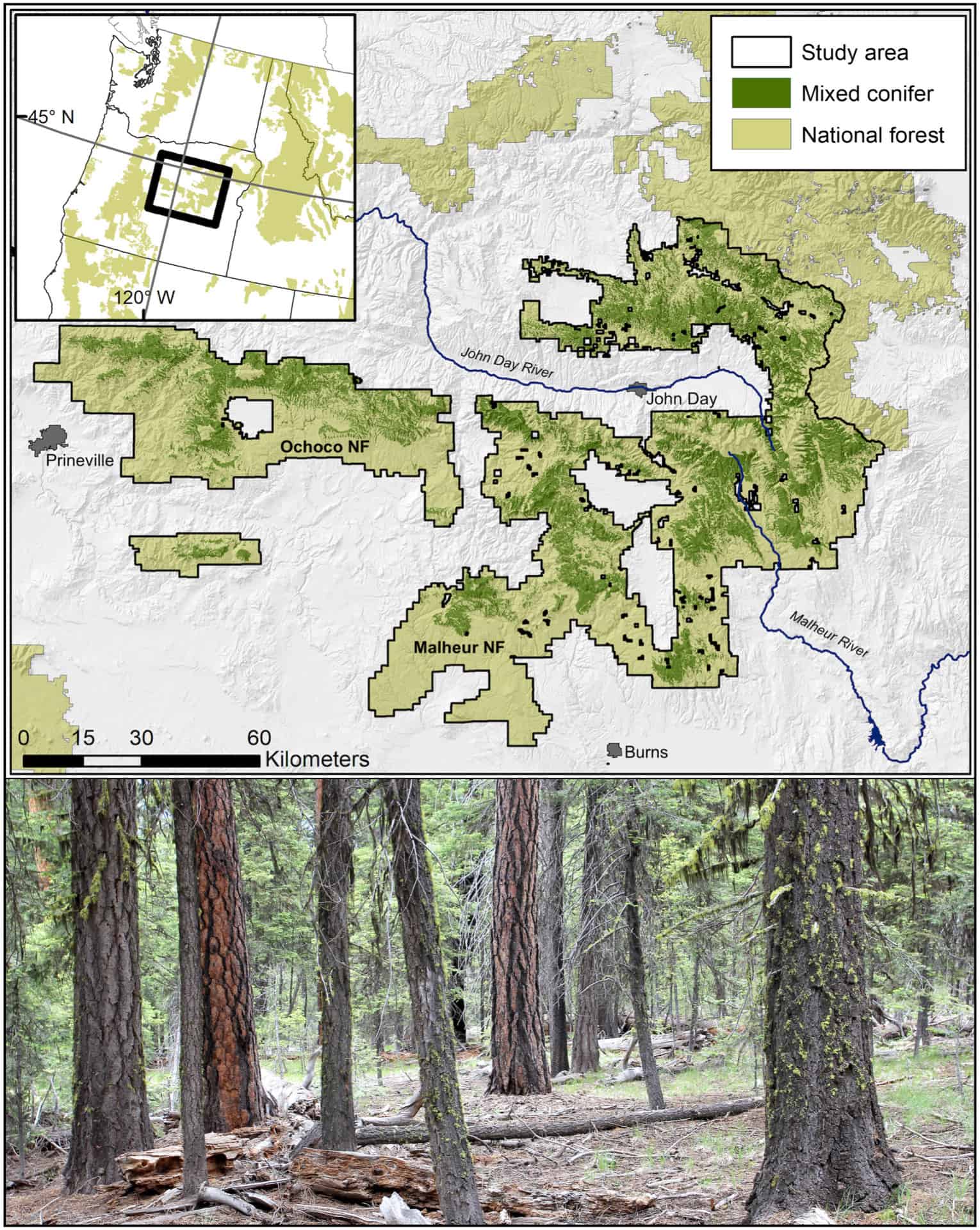

• Different actions and priorities are appropriate across the landscape: 1) near communities, the primary goal should be protecting lives and property through steps like defensible space, structure hardening, emergency response, improved ingress/egress, and reducing unplanned human ignitions; 2) in the mixed forest landscape, we should work to increase forest resilience and mature forest structure using actions like ecological forest thinning and prescribed and managed fire while reducing unplanned human ignitions and hardening infrastructure; 3) in roadless and wilderness areas, the primary management tools should be cultural burning as well as prescribed and managed fire.

• There is a need for an all-lands approach, including public-private and tribal partnerships, to achieve these goals.

• We support the commercial use of woody material removed from forests (e.g., saw logs, mass timber manufacturing, woody biomass for heat and electrical generation, and added value wood products development) where the goal is increasing forest health and resilience and as long as species and ecosystems needs are met.

The letter even has a very nice glossary.

I find nothing to disagree with here (I could get picky about specific words but..). I’ve found that for some E-NGOs, woody biomass is a non-starter (it seems to invoke Europe and southeastern US pellet exports), and and some seem to be against commercial use of woody material from National Forests. I think it’s important to note that these groups (who have to live with the “burn in piles or do something else” challenge staring them in the face) support useswith constraints (“when the goal is”.. and “as long as”). Certainly the devil is in the details, but some groups seem to assume that those details can’t be handled appropriately through existing mechanisms or those to be developed in the future.

Does anyone have a similar statement from groups in other western states?