Maybe this is one possible (small) advantage of state ownership (vs federal) of public lands in one state. In Montana you (and I mean you, or any environmental group) can bid on a 25-year “conservation license” in lieu of a timber sale. In what I believe may be a first in Montana, there was such a high bidder. It’s maybe a fairly unique situation, where adjacent landowners could afford to pony up the $100ks for what appears to amount to a limited-term scenic easement. This makes some sense for the state if the goal for land management is dollar returns. Of course the actual timber bidder is protesting it. Both sides have raised questions about what the statutory language for state lands means when it says: “secure the largest measure of legitimate and reasonable advantage to the state.” Should it include the “benefits” of roads that would be built (but not the environmental costs); should it include the long-term economic value of being able to resell the same timber in 25 years? (Is this a good idea for public lands?)

Role of local and state governments

The myth of “coordination”

In recent years this the idea of “coordination” has been sold to local governments as a legal tool to make federal land managers do what the locals want with national forest plans. It’s a myth that periodically needs busting. This article describing the response of the Malheur National Forest and a document from the Northern Region provides a pretty good summary of the history and reality.

“Based on recent local government resolutions or ordinances and letters to some national forests, it appears that some local government officials believe the (National Forest Management Act) coordination requirement means the Forest Service must incorporate specific provisions of county ordinances into forest plans or that the Forest Service must obtain local government approval before making planning decisions,” Hagengruber said.

“This position overstates the NFMA obligation of the Forest Service,” he continued. “The statute does not specify what actions are required to coordinate Forest Service planning with local government planning, and it does not in any way subordinate federal authority to counties.”

“Rather,” he continued, “the Forest Service must consider the objectives of state and local governments and Indian tribes as expressed in their plans and policies, assess the interrelated impacts of these plans and policies, and determine how the forest plan should deal with the impacts identified.”

Nantahala-Pisgah forest plan comments

The third of three articles on the results of a Carolina Public Press Freedom of Information Act request for the more than 6,000 comments focuses on governmental emails.

Hmmm … maybe this is one of those articles where we should debate the author’s approach, especially his choice of who to interview (somewhat tongue-in-cheek). Here is one thing a “retired Forest Service bureaucrat” had to say …

Mostly absent from the collaborative groups are elected officials. While elected officials represent residents, Friedman said, they are seldom effective members of stakeholders groups that strive for collaborative solutions.

“They may not share the level of passion and knowledge of individuals, experts and special interest groups that participate in stakeholders groups,” she said.

An interesting theory. Friedman had quite a few things to say. (Maybe she can explain why the locals insist on calling this the Pisgah-Nantahala National Forest.)

(The article includes links to a number of articles on this Forest’s plan revision process.)

Another Piece of the Executive Order Puzzle- WGA MOU with Forest Service

So far this week. we’ve had (1) the Executive Order by President Trump posted by Jon dated Dec. 21, (2) the Letter by Governors Inslee, Newsom, and Brown dated January 9th that Steve posted here. But another similar sounding piece of information is an MOU that was signed by the Western Governors Association Dec. 18th. IMHO, the Western Governors always seem to be working on useful things, but generally don’t seem to get much coverage in the media. Anyway, here’s the MOU. Sounds like everyone’s in agreement about what needs to be done. Maybe Inslee, Newsom and Brown are trying to get to the head of other western states’ funding pack? Or there’s some political angle that is not obvious (at least to me).

The purpose of this MOU is to establish a framework to allow the Forest Service and WGA to work collaboratively to accomplish mutual goals, further common interests, and effectively respond to the increasing suite of challenges facing western landscapes. Federal, state and private managers of forests and rangelands face a range of urgent challenges, among them catastrophic wildfires, invasive species, degraded watersheds, and epidemics of insects and disease. The conditions fueling these circumstances are not improving. Of particular concern, are longer fire seasons, the rising size and severity of wildfires, and the expanding risk to communities, natural resources, and firefighters. To address these issues, the Forest Service announced a new strategy outlining plans to work more closely with states to identify landscape-scale priorities for targeted treatments in areas with the highest payoffs.

The Forest Service will partner with state leaders and work shoulder-to-shoulder to co-manage risks, and identify land management priorities, using all available tools to reduce hazardous fuels, including mechanical treatments, prescribed fire, and management of unplanned fire in the right place at the right time, to mitigate them.

A key component of the Forest Service’s new shared stewardship strategy is to prioritize investment decisions on forest treatments-in direct coordination with states-using the most advanced science tools to increase the scope and scale of critical forest treatments that protect communities and create resilient forests and rangelands.

As the chief elected officials of states, Governors expect to engage with federal officials on the formulation and execution of public policy. Governors also have specialized knowledge of their states’ environments, resources, laws, culture, and economies that is essential to informed federal decision-making. By operating as authentic collaborators, the states and federal government can improve their service to the public by creating more efficient, effective, and long-lasting policy.

As far as I can tell, there is not another similar MOU with Interior.

Another WGA item of note:

Initiation of Collaborative Conservation Task Force (Dec. 2018)

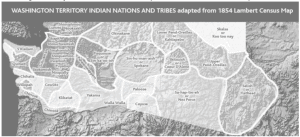

Supreme Court may reinterpret tribal treaty rights on national forests

Here’s a pending Supreme Court case, Herrera v. Wyoming, that hasn’t shown up in the Forest Service litigation summaries. The federal government is defending the right of a Native American to hunt on the Bighorn National Forest without complying with state hunting laws. If they lose, tribal treaty rights, as currently understood, could be severely diminished. The hearing is scheduled for January 8.

When the native tribes ceded their lands to the federal government, the language in the treaties typically preserved their rights to various uses and activities on indigenous lands that were not included within the new reservation, for which the treaties used the terms “open and unclaimed” or “unoccupied” lands. Much of that land is now part of national forests. Here is how the Forest Service interprets the language referring to those lands:

The term applied to public domain lands held by the United States that had not been fenced or claimed through a land settlement act. Today, “open and unclaimed lands” applies to lands remaining in the public domain (for the purposes of hunting, gathering foods, and grazing livestock or trapping). The courts have ruled that National Forest System lands reserved from the public domain are open, unclaimed, or unoccupied land, and as such the term applies to

reserved treaty rights on National Forest System land.

In the case currently pending before the Supreme Court the State of Wyoming has argued that this is not true (they also argue that the lands became “occupied” when Wyoming became a state):

The parties further dispute whether the Bighorn National Forest should be considered “unoccupied lands” for treaty purposes. Herrera and the federal government emphasize that the proclamation of a national forest meant the land could no longer be settled, which they argue was the historical standard for occupation. Yet Wyoming argues that physical presence should not be the test, especially given the West’s expansiveness. According to Wyoming, the federal government’s proprietary power over its own lands, including its decisions to exclude hunters, demonstrates that the land was effectively occupied when it became a national forest.

Courts have held that the federal government has a substantive duty to protect ‘to the fullest extent possible’ the tribal treaty rights, and the resources on which those rights depend. If Wyoming were to win their argument, treaty rights to accustomed tribal uses of national forests would no longer exist. Because the federal government is defending the tribal interests in this case, one might think that the Forest Service would continue to protect these rights even without the treaty obligation. However, in the past they have disagreed with tribes on issues such as campground fees and desired salmon populations.

Montana County rains on land deal

It is a time-tested and popular model. A private landowner is willing to sell land or conservation easements to the government. A third party conservation group steps in to provide bridge funding and/or ownership until the government can fund the purchase. In this case, involving the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation as the intermediary:

“The project, which was in its very early stages, would provide some valuable new access points in the area as well as protection from development along a stretch of Sheep Creek, a tributary of the Smith River, he said. In addition to the 4,000 acres purchased and then resold to the Forest Service, the checkerboard pattern of land ownership would mean access to an additional 7,000 acres of public land.”

While Meagher County (pronounced “mar”) doesn’t have any authority to influence the deal, it is attempting to do so by issuing a resolution opposing it, citing “potential loss of tax revenue, issues with federal land ownership and management, and the question of whether a land swap could open access without expanding federal land ownership.” The resolution says, “that the commission respects private property rights and supports tourism but continues to oppose expanded federal ownership.” (Funny that they don’t mention elk hunting/hunters, which has to be a key benefit.) Their opposition may affect how the project competes for funding, and whether RMEF wants to stay involved.

The Forest Service, to its credit, is looking out for the “greatest good” and not bowing to nimbyism or political ideology.

“We acknowledge Meagher County’s resolution and recognize their position regarding the Holmstrom Sheep Creek proposal,” said Lisa Stoeffler, acting forest supervisor. “We appreciate that our working relationship with the commission allows for open discussions, especially related to increased recreational public lands access and the improvement of crucial fish and wildlife habitat conservation areas within the county. The Forest plans to submit two project requests for LWCF funding, one of which will include Holmstrom Sheep Creek. In our request packet, we will fully disclose the Commission’s resolution regarding the project.”

These have normally been seen as “white hat” projects in the past, but under this Administration, the Forest Service may find out that white is the new black.

Collaborative flops

The Colville National Forest released a draft Record of Decision for its revised forest plan on September 8. During the planning process, a collaborative group, the Northeast Washington Forestry Coalition submitted a proposal to designate more than 200,000 acres of new wilderness, to be offset by increased logging on other parts of the Forest and building new trails for mountain bikers, motorcyclists and ATV riders, who would lose access to some trails if Congress approved new wilderness. The revised plan proposed by the Forest includes only 60,000 acres of wilderness recommendations.

I guess that’s good news if you think that local collaboratives have too much influence on national forest decisions and/or if you are a proponent of logging. But wait! It turns out that the most influence was wielded by the local governments, and the local timber company isn’t happy about that.

Russ Vaagen, vice president of Vaagen Brothers Lumber Co. and NEWFC board president, formally objected to the draft plan in a Nov. 6 letter. In the letter, he said the Forest Service’s decision was “skewed” by special interest groups. “The Colville National Forest belongs to all citizens of Washington and the United States,” he wrote. “Ferry, Stevens and Pend Oreille county commissioners represent just a tiny fraction of these citizens.” Later in the letter he said it’s unavoidable that locals will have “personal, financial interests” in what happens to federal land, but that those interests should “have no bearing on federal land management issues.”

This sort of left my head spinning. Maybe it’s because they didn’t get the increased logging either (I don’t know if that’s true)? Or maybe it’s that the “collaborative” part should win out over merely “local.” Or did the “local” actually use an end-run to obtain a top-down approach from an administration hostile to new wilderness?

I’ll go out on a limb here and suggest that since decisions to designate wilderness are inherently and legally political, this may legitimize and enhance the value of a local collaborative approach. Of course all is not lost on the Colville; the collaborative approach could count for something when the collaborative makes an end-run around the Forest Service to obtain wilderness legislation, since it can undercut an agency position that the Forest Service is doing what the public wants.

In another wilderness squabble involving an end-run by local governments to reduce wilderness protection, three counties in Wyoming have chosen to bypass a statewide collaborative process and support federal legislation that would eliminate wilderness study areas without designating any new wilderness.

Titled the “Restoring Public Input and Access to Public Lands Act of 2018,” HR 6939 would remove wilderness study designation and associated protections from approximately 400,000 federal acres in Lincoln, Big Horn and Sweetwater counties (see the bill below). The three counties declined to participate in a years-long consensus-based investigation of the wildlands. Saying the wilderness-study designation “prevents access, locks up land and resources, restricts grazing rights, and hinders good rangeland and resource management,” Cheney introduced her measure Sept. 27. It marked the third time she bypassed the Wyoming Public Lands Initiative sponsored by the Wyoming County Commissioners Association. Across the state, 777,766 acres of BLM and Forest Service property are protected by wilderness study designation. WPLI sought a single statewide wilderness bill to resolve study-area status. A majority of commissioners in the three counties, however, responded to Cheney’s early 2018 call for legislation before the WPLI process played out.

I’m cheering for the collaboratives here, too.

Polis Ideas on Public Lands Policy

The first thing I noticed about Polis’s public lands policy was that I found it under a tab called “Environment” but the actual link was called https://polisforcolorado.com/keep-co-wild/, as in “keep Colorado wild.” Most of the suggestions were about actually about “public lands”. They included supporting federal funding for LWCF and non-game species, but some were related to the State, including funding for state agencies, wildlife crossings and changes to bear policies.

Create Colorado Conservation and Recreation Districts

Colorado is home to 42 state parks and 13 National Parks which welcome millions of visitors per year. I will create Colorado Conservation and Recreation Districts that harness the economic power of these landscapes to highlight Colorado’s natural outdoor assets and promote each community’s unique attractions. Through a coordinated effort alongside conservationists, sportsmen and sportswomen, and the outdoor recreation industry, we will provide educational opportunities and access to grant funding to support conservation and recreational entrepreneurship. Housed under the shared jurisdiction of the Office of Economic Development and Colorado Parks & Wildlife, this program will help more Coloradans forge a special connection with our natural resources, further strengthening the Colorado economy.

This seems good, like “working together better”, except it seems like more small businesses (entrepreneurship) but the National Forests and BLM seem conspicuously absent. And yet, driving around Colorado in the summertime, most recreationists I see are indeed recreating on National Forests or BLM. I wrote the Polis campaign and asked if National Forests and BLM were left out intentionally, but have not yet heard back. But do Coloradans need “special help”? connecting with our outdoors? Do we need to promote more recreation businesses? Or will more recreation businesses mean more recreation and more impacts on the environment? Why is using State funds to support an industry (other than environmental cleanup) in the “environmental policy” section?

Oppose Selling Our Public Lands to the Highest Bidders

As governor, I will fight any attempt to sell our public lands to the highest bidder or diminish them in any way. Nearly a third of our state is made up of public lands, and these lands belong to all Coloradans, no matter their background, zip code, race, or income. Our public lands, clean air, and rivers are critical to protecting our fish and wildlife habitat, providing the public with places to hunt and fish, ski, climb, bike, raft, and enjoy the Colorado outdoor experience. The activities are foundational to Colorado’s recreation economy, providing good-paying jobs for thousands of Coloradans and attracting national attention through events like the Outdoor Retailer trade show. Thoughtful and effective conservation of these resources is paramount in supporting Colorado’s strong outdoor economy and way of life.

As we know, no one is planning to sell off federal lands. Perhaps someone was planning to sell off state lands? According to Ballotpedia, 35.9% of Colorado is federal land, which would mean if you add State and County land, it’s got to be more than a third for total “public land”, the way I would define it. I couldn’t easily find the total acres of State land in Colorado. Some of it is in State Parks, and much is owned by the State Land Board, which appears to have minerals and agricultural leases. I wonder if those leases are defined as “diminishing public lands in any way”? Are those kind of leases appropriate to State lands but not Federal? And where do state and federal statutes fit into this?

Ensure Colorado Has a Voice in Federal Decisions on its Public Lands

Coloradans understand in our core that public lands have value far beyond industrial development. As governor, I will work to ensure that our public lands are protected from overzealous development and that every Coloradan has every opportunity to have their voices heard in these decisions that affect the future of these lands. Colorado deserves a strong seat at the table here and in D.C. when it comes to conversations about what happens to the land, wildlife, trails, and resources in our backyards.

Hmmm. Industrial development on public lands. I don’t know exactly what he means by “overzealous development” (we have underground coal mines, oil and gas, so perhaps it’s code for oil and gas?) But wind and solar farms also look pretty industrial, and in the Energy section we reviewed yesterday here, he said he would help reduce red tape on those. I guess that would be “zealous” development.

But this one is particularly interesting in light of our discussion last week about “everyone in the country having an equal voice in Federal lands.” I agree that “Colorado deserves a strong seat at the table here and in D.C…about what happens.. in our backyards?” But I wonder if he feels the same way about Utah?

Greater sage-grouse amendment amendment

Three years ago the Forest Service had this to say about the greater sage-grouse:

Two US Forest Service Records of Decision and associated land management plan amendments are the culmination of an unprecedented planning effort in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management to conserve greater sage-grouse and its habitat on National Forest System lands and Bureau of Land Management-administered lands.

Last week it was this (and they initiated a public comment period):

Since approving the plan amendments in 2015, the Forest Service has gathered information and determined that the conservation benefits of Forest Service plans in Nevada and other states can be improved. That is, through repeated scoping, close collaboration with state and other federal agencies, and internal review, the Forest Service has identified proposed changes in the text of the greater sage-grouse plan amendments which would improve their clarity and efficiency and better align them with the Bureau of Land Management and state plans.

Specifically, the Preferred Alternative makes modifications to land management plans within the issue areas of: Habitat management area designation, including designating sagebrush focal areas as Priority Habitat Management Areas compensatory mitigation and net conservation gain; minerals plan components and waivers; exceptions and modifications; desired conditions; livestock grazing guidelines; adaptive management; treatment of invasive species; and changes to clarify text and eliminate errors and redundancies.

Oddly, it sounds like all of the new information must say that sage-grouse are doing better than we thought three years ago and/or they are less vulnerable to oil and gas drilling than we thought three years ago. The most important change in forest plans is probably this one (from an AP article):

The Obama administration created three protection levels for sage grouse. Most protective were Sagebrush Focal Areas, followed by Primary Habitat Management Areas and then General Habitat Management Areas. The Forest Service plan reclassifies the 1,400 square miles (3,600 kilometers) of Sagebrush Focal Areas as primary habitat.

The focal areas allowed no exceptions for surface development, while primary habitat allowed for limited exceptions with the agreed consent of various federal and state agencies. Under the new plan, the cooperation of states and some federal agencies to exceptions in primary habitat will no longer be needed for some activities but can be made unilaterally by an “authorized officer,” likely an Interior Department worker. That appears to be an avenue for opening focal areas to natural gas and oil drilling.

This amendment decision will be subject to the 2012 Planning Rule requirements for species viability and species of conservation concern (SCC) (from the DEIS):

… the FS is considering the effect on the greater sage-grouse as a potential SCC for each LMP that would be amended by this decision. The analysis in this DEIS shows that the amendments maintain ecological conditions necessary for a viable population of greater sage-grouse in the plan area for each LMP to which the amendments would apply.

Recall that the current conservation strategy was “generally viewed as keeping the bird from being listed for federal protections under the Endangered Species Act.” What will the Zinke that is charge of the Fish and Wildlife Service have to say to the Zinke that is in charge of the BLM (and apparently the Forest Service)? Why does this remind me of political appointee Julie McDonald’s interference with decisions about lynx? Is it more about a new boss than about new science? “A federal lawsuit is likely.”

Some more background is provided here.

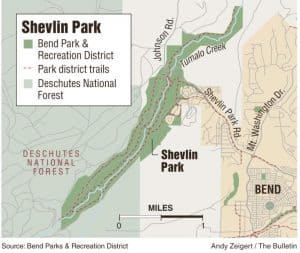

Zoning in the WUI

Another example of someone doing something right. But it’s not the Forest Service; the Deschutes National Forest was listed as an agency that “either had no comment or did not respond to the notice.” (The forest plan management area for much of the adjacent national forest is something called “other ownership,” but I couldn’t find what that means.)

Developers said they’ll cap the number of homes in the new zone at no more than 187 units — 100 on the north property and 87 on the south. Lots would all be designed to prevent risks of wildfire spreading and protect wildlife habitat, said Myles Conway, an attorney for Rio Lobo investments. Plans also call for a 42-acre wildlife conservation area adjacent to Shevlin Park.

The environmental watchdog group Central Oregon LandWatch, which fought to keep Bend’s urban growth boundary from encompassing the affected areas, “strongly supports” the so-called transect zone, LandWatch staff attorney Carol Macbeth said.

“It’s critical to take a new approach to development in the wildland-urban interface, and the Westside Transect is that approach,” Macbeth said. “It will provide a 4.5-mile first line of defense against approaching fires for developments like Awbrey Glen as fires approach from the west and northwest.”