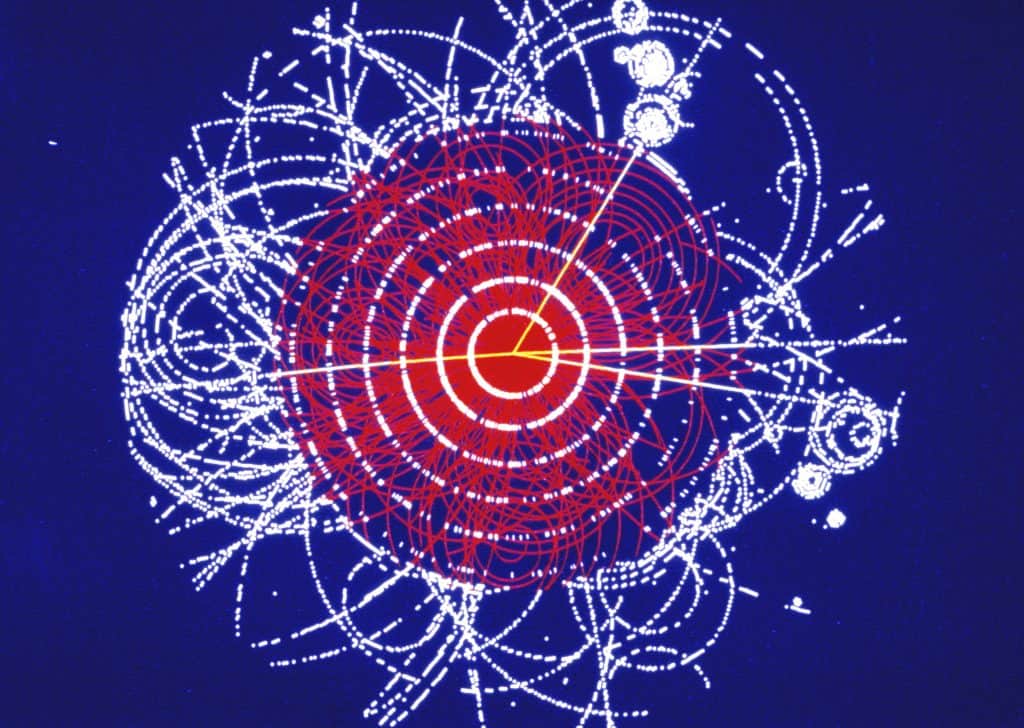

Science & Society Picture Library / Getty

When we talk about “science tells us” and so on, sometimes it’s good to reflect on the abstraction of “science” and what makes any human activity “science.”

Dan Sarewitz looked at a couple of different perspectives, from theoretical physics to improving antifreeze formulations in this piece..

What, then, joins Hossenfelder’s field of theoretical physics to ecology, epidemiology, cultural anthropology, cognitive psychology, biochemistry, macroeconomics, computer science, and geology? Why do they all get to be called science? Certainly it is not similarity of method. The methods used to search for the subatomic components of the universe have nothing at all in common with the field geology methods in which I was trained in graduate school. Nor is something as apparently obvious as a commitment to empiricism a part of every scientific field. Many areas of theory development, in disciplines as disparate as physics and economics, have little contact with actual facts, while other fields now considered outside of science, such as history and textual analysis, are inherently empirical. Philosophers have pretty much given up on resolving what they call the “demarcation problem,” the search for definitive criteria to separate science from nonscience; maybe the best that can be hoped for is what John Dupré, invoking Wittgenstein, has called a “family resemblance” among fields we consider scientific. But scientists themselves haven’t given up on assuming that there is a single thing called “science” that the rest of the world should recognize as such.

The demarcation problem matters because the separation of science from nonscience is also a separation of those who are granted legitimacy to make claims about what is true in the world from the rest of us Philistines, pundits, provocateurs, and just plain folks. In a time when expertise and science are supposedly under attack, some convincing way to make this distinction would seem to be of value. Yet Hossenfelder’s jaunt through the world of theoretical physics explicitly raises the question of whether the activities of thousands of physicists should actually count as “science.” And if not, then what in tarnation are they doing?

When Hossenfelder writes about “science” or the “scientific method” she seems to have in mind a reasoning process wherein theories are formulated to extend or modify our understanding of the world and those theories in turn generate hypotheses that can be subjected to experimental or observational confirmation—what philosophers call “hypothetico-deductive” reasoning. This view is sensible, but it is also a mighty weak standard to live up to. Pretty much any decision is a bet on logical inferences about the consequences of an intended action (a hypothesis) based on beliefs about how the world works (theories). We develop guiding theories (prayer is good for you; rotate your tires) and test their consequences through our daily behavior—but we don’t call that science. We can tighten up Hossenfelder’s apparent definition a bit by stipulating that hypothesis-testing needs to be systematic, observations carefully calibrated, and experiments adequately controlled. But this has the opposite problem: It excludes a lot of activity that everyone agrees is science, such as Darwin’s development of the theory of natural selection, and economic modeling based on idealized assumptions like perfect information flow and utility-maximizing human decisions.

Of course the standard explanation of the difficulties with theoretical physics would simply be that science advances by failing, that it is self-correcting over time, and that all this flailing about is just what has to happen when you’re trying to understand something hard. Some version of this sort of failing-forward story is what Hossenfelder hears from many of her colleagues. But if all this activity is just self-correction in action, then why not call alchemy, astrology, phrenology, eugenics, and scientific socialism science as well, because in their time, each was pursued with sincere conviction by scientists who believed they were advancing reliable knowledge about the world? On what basis should we say that the findings of science at any given time really do bear a useful correspondence to reality? When is it okay to trust what scientists say? Should I believe in susy or not? The popularity of general-audience books about fundamental physics and cosmology has long baffled me. When, say, Brian Greene, in his 1999 bestseller The Elegant Universe, writes of susy that “Since supersymmetry ensures that bosons and fermions occur in pairs, substantial cancellations occur from the outset—cancellations that significantly calm some of the frenzied quantum effects,” should I believe that? Given that (despite my Ph.D. in a different field of science) I don’t have a prayer of understanding the math behind susy, what does it even mean to “believe” such a statement? How would it be any different from “believing” Genesis or Jabberwocky? Hossenfelder doesn’t seem so far from this perspective. “I don’t see a big difference between believing nature is beautiful and believing God is kind.”