It’s always interesting to take our US-western federal lands-collaborative governance experience and relate it to other countries. I like that the authors wrote a user-friendly intro to their study. There’s a bit of academic-ese to wade through but the diversity of approaches and the categories give much to think about.

How can humanity address the vast sustainability challenges that we face? Today there is no shortage of ideas and recommendations. Yet, what do they actually do for society? In Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, a supercomputer is famously tasked with calculating the answer to the ultimate question of life, the Universe, and everything. After 7.5 million years, it answers “42”. An answer of little use to anyone when the original question remains a mystery.

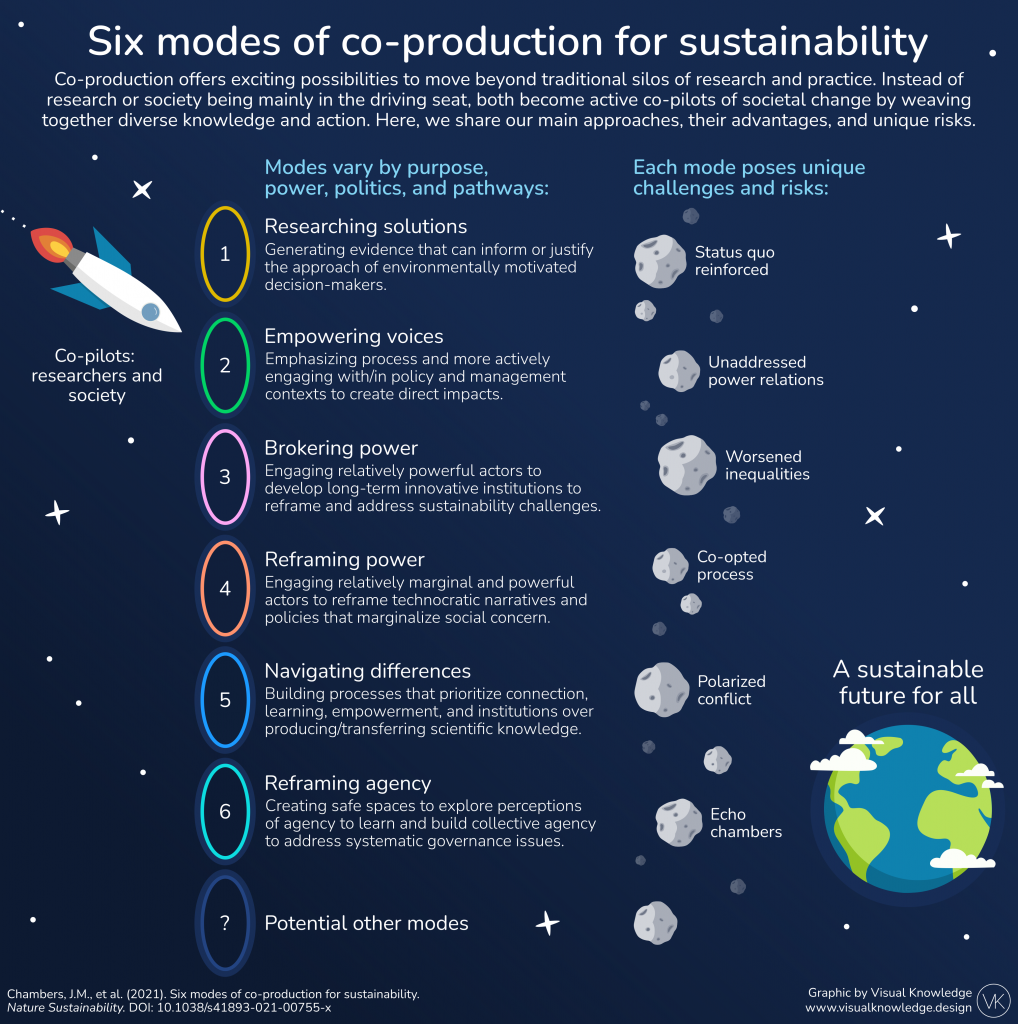

This metaphor is apt for the state of many academic disciplines: research churns out advice, yet often with poor connection to the world beyond academia, where progress is at best incremental. One response to this is “co-production” – processes that connect researchers and diverse societal actors to grow critical insights in ways that promise to spur direct action. Instead of a single lead researcher (or computer), co-production entails collaborative work to navigate often contrasting views regarding what questions matter, and how their exploration can generate societal change.

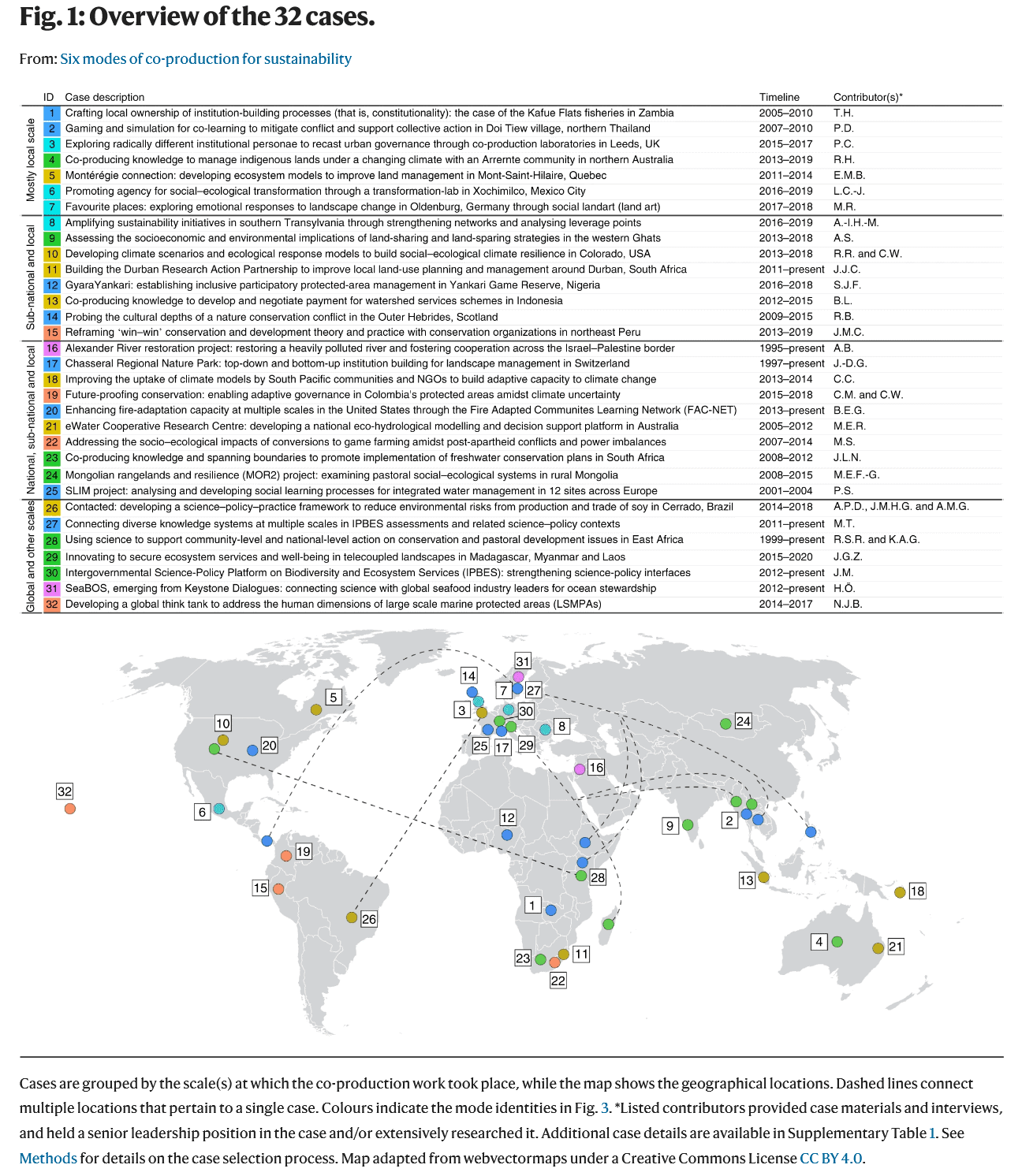

Co-production is widely applied to address sustainability challenges, and action is urgently needed. Yet, questions remain around the many proliferating concepts and methods that make up co-production. In response, our initial answer was also 42 – in this case, 42 scholar practitioners deeply engaged in co-production. Together, we mapped out commonalities and differences across 32 initiatives that designed to connect diverse sectors and sustainably develop ecosystems at local to global scales in six continents. We asked ourselves: How do our approaches differ? Why? What are the implications?

In our new study, “Six modes of co-production for sustainability”, we share our collective insights via a heuristic tool designed to support diverse change agents – researchers, policy makers, activists, community leaders, and CEOs – to reflect on how they attempt to link diverse knowledge and action. The six modes we identify vary in their purpose for using co-production – to solve predefined problems, or to reframe problems; understanding of power – focusing on changing people’s behaviour, or more systemic issues; approach to politics – empowering marginalized actors, or influencing powerful actors to yield power; and pathways to impact – by primarily producing scientific knowledge, or through more integrated forms of knowing, relating and doing. These differences influence the kinds of outcomes that are possible, as well as the critical risks they pose. Here we offer a brief tour of six such initiatives.