Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has upheld the Telegraph Vegetation Project on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest, except for one question about the location of the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI). The case was previously described on this blog here. That description included this allegation by plaintiffs:

Agency used non-federal definition of the Wildland Urban Interface

“While the lynx amendment allows logging in the Wildland Urban Interface, it also defines the Wildlife Urban Interface to be within one mile of communities,” Garrity explained. “But the Forest Service used a new definition provided by local counties and then remapped the Wildland Urban Interface to include areas over five miles away from communities.”

The court remanded the decision for 50 acres of the 5000-acre plus area to be treated, and left the record of decision in place while the Forest Service completes its reevaluation:

“The Forest Service has acknowledged that it erred in calculating the wildland-urban interface for the project area. The Forest Service estimates that, once it has corrected its error, 50 acres of forest that it had planned to treat may no longer be eligible for treatment. If that estimate proves correct, the Forest Service represents that it will not treat those 50 acres. We grant the government’s request for a voluntary remand to allow the Forest Service to undertake the necessary reevaluation.”

I have been interested in how WUI is identified, by whom, and using what process under what authority – especially the role of non-federal parties. WUI is generally identified based on the Healthy Forest Restoration Act of 2003 (HFRA). Areas identified using that process qualify for streamlined projects in accordance with HFRA, and may be eligible for particular funding. However (in accordance with HFRA), WUI projects are still subject to requirements of the governing forest plan. Management direction for lynx is part of the forest plan, and this article (like plaintiffs) suggests it imposes greater restrictions on part of this project:

“In the second portion of the court’s order, the Forest Service proposed logging and thinning in areas defined as the “wildland-urban interface,” which is where houses or cabins meet the forest. Regulations related to lynx allow the removal of some trees and vegetation in lynx habitat if it falls within the wildland-urban interface and if the agency shows it is part of a wildfire mitigation project. The alliance inspected the area and reported only a handful of houses. The Forest Service conceded in court documents that it erred in calculating the size of the wild-land urban interface based on discrepancies between what qualifies.”

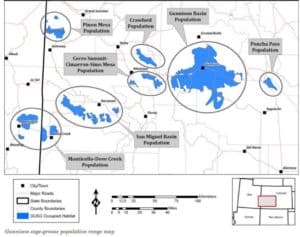

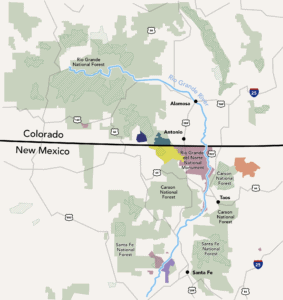

However, this actually indicates that the problem was in the definition of “community” (based the on number of houses), rather than the distance from one. In fact, the Northern Rockies Lynx Management Direction refers to WUI “as defined by HFRA.” Those definitions and criteria for “WUI” and “at risk community” are summarized by the Forest Service here. Although which communities are to be included (they can self-identify) are mostly listed in the Federal Register, that doesn’t address their boundaries. The district court opinion upheld the Forest Service WUI designation, stating that, “The Powell County Plan does not begin with the HFRA definition; it creates its own, “and “the Court is not persuaded by Council’s attempt to discredit the map provided by the Forest Service in the Telegraph Project EIS” based on that county plan. Yet it sounds like the map may have been wrong in this case. This all reminds me of my take-home from my Forest Service days that “WUIs are fuzzy.”

Here’s why this might be important to planning. I agree with the idea that forest plans (like the lynx direction) should identify areas with differences in long-term management that result from a wildland-urban influence. However, if the WUI definition refers to another source (HFRA and a local plan), instead of being specifically defined in the plan itself through criteria and/or a map, there may be confusion about where and how the plan applies (as seems to be the case here). (Yes I’m criticizing the lynx strategy for doing that; they didn’t take my advice.) In addition, if external decisions about WUI locations change, the Forest Service may have to publicly consider whether to adopt that change in its forest plan (that situation wasn’t addressed in this case). I’m also contrasting “decisions” with new “information” that affects how an existing decision applies (e.g. someone building a new house), which must be considered in a planning context but doesn’t necessarily trigger a plan amendment. (A court has held that even changes in something like criteria for maps of lynx habitat must be considered in a public planning process when forest plan direction is tied to it.)

(The other issue addressed by the 9th Circuit in its short opinion was the ESA consultation process for grizzly bears. The court approved a consultation process that tiered to forest plan decisions and consultation, which lead to streamlined project consultation. The value of forest plan consultation has been questioned, but that value is evident here.)