Too many years ago, I served on a timber industry committee charged, among other things, with figuring out whether it was better to advocate the calculation of “allowable sale quantities” in board or cubic feet. Board foot measure estimates how much lumber can be sawn from a log, with allowances for saw blade width (“kerf”), slabs (the left-overs after squaring off a round log), and sawing strategy. Cubic foot measure is the geometry-based volume of a log.

Ceteris paribus, the number of board feet equivalent to one cubic foot is proportional directly to log diameter. For example, a small-diameter log has a bf/cf ratio of about 4, while a large-diameter log’s ratio is about 6.

Today, almost all serious measures of timber are made in cubic feet, except for pulpwood and biomass, which are measured by weight. That’s because cubic foot measure is widely regarded as a more accurate representation of total wood volume, less subject to the vagaries of milling technology and scaling judgment.

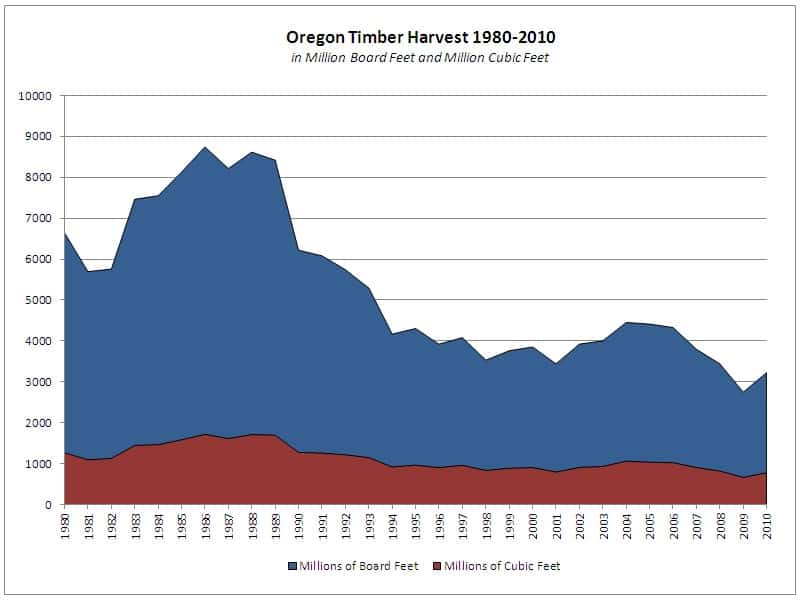

Which measure one chooses makes a difference in how one sees the world of wood production and supply. “Everyone” knows that Oregon’s timber harvest has dropped precipitously since the early 1990s. And, so it has, measured in board feet (the blue-line curve).

But a funny thing happens when Oregon’s harvest is measured in cubic feet (the red-line curve). Not nearly so dramatic a decline. The reason is pretty simple. Oregon’s plantation forests grow a whole lot of wood, producing much more growth annually than the old forests the plantations replaced. Cubic foot measure, which is much less sensitive to tree diameter, more accurately captures that volume than does board foot measure.

Here’s another way to look at it. According to the Oregon Forest Resources Institute, 60% of forestland in the state is federally owned, and that land provides 12% of the total harvest. The 19% owned by “large private” owners produces 73% of the total harvest.

Here’s yet another way to look at it. Oregon’s non-reserved national forest timberland has an average productivity of 79 cubic feet/acre/year compared to Oregon’s average timber industry acre at 127 cubic feet/year (weighted averages calculated from Table 11).

Andy’s point here is the industry got the most productive land. Industry has access to “more than half” of the productive capacity of Oregon’s forests when you include the private non-industrial tracts. plus a portion of the federal land.

Come to think of it, what are they complaining about? Oregon’s timber industry has got it sooo easy. Consider this:

> Control and access to vast timberlands on private and public lands;

> Industry has over a billion board feet of federal timber currently under contract in the state of Oregon from the National Forests alone, not including BLM.

> Highly favorable tax treatment. most of their small tax payments pay for suppressing fire on their lands and to run ubiquitous TV ads promoting clearcutting;

> The least burdensome forest practices act on the entire west coast;

> Congressmen form both parties at their beck and call;

> Fistfulls of county commissioners who want to recouple the counties to federal timber receipts even at the expense of the counties own economic interests;

> Near complete control of the policy-making machinery in Salem with majority control of the board of forestry and legislators and governor doing their bidding for a pittance;

> Scientists at OSU trying to shrink riparian reserves and restart clearcutting on federal land under the guise of “ecological forestry” – all before we figure out how much forest we need to conserve to mitigate for barred owls and climate change.

> A culture that worships capitalism so much lets the oligarchy of big automated mills drive virtually all the little community job-creators out of business.

Steve and Andy: I think you both are looking at the same elephant, just describing different body parts.

Essentially, timber industry land is 50% more productive by acre; the feds own 300% more land in Oregon than industry; the feds produce 17% as much harvest as industry.

If the federal lands were as productive (harvest-wise, not biologically) as the industrial lands, they would have to increase annual production (based on these numbers) by at least 400%.

Is that close to accurate?

When people say “productive” do they mean the capacity if managed with some unidentified set of practices? Hard to pick out the practices from the underlying capability of the land to grow trees.

Sharon: That’s an important distinction. When I first started working in the woods, forestland productivity was defined in terms of “site classes.” Site Class I grew the most fiber annually per acre, whereas Site Class V could hardly produce merchantable timber at all.

After a few years we were able to discover that it is fairly easy to change the site class of an area (supposedly restricted by local weather and soil conditions) via weed control, animal management, planting stock quality, and tree spacing.

It is entirely possible that industrial lands are much more “productive” per acre because they are being intensely managed for timber production. It’s also possible that the soil and weather on the industrial lands are better for growing trees than on the federal lands. BLM O&C lands, though, seem better for timber growing than many industrial lands, and certainly more productive in that regard than high elevation USFS lands or federal (and private) lands east of the Cascades.

(Hurray for the Boston police! And for high-speed Internet.)

I agree with Bob’s arithmetic and explanation on all counts.

To elaborate regarding “productivity,” site class is measured for “natural,” unmanaged stands. It is more useful as a relative measure, e.g., industrial lands 50% more productive than FS lands, than as an absolute prediction of how much timber an acre can grow.