Every time I think public lands issues are contentious, I just look at my climate science newsfeeds and thank Gaia for our community! But I think for those of us who haven’t been up close and personal with the science biz,it’s important to to understand some of the debates about advocacy vs. objectivity and how that plays out. It’s kind of funny sometimes being an Old Person. I remember when I was a “Population Geneticist”. Somewhere along the lines, after I graduated with my Ph.D., some of my colleagues started calling themselves “Conservation Geneticists.” During a discussion, one of these colleagues called me an “Exploitation Geneticist” ;). If you didn’t live through this yourselves, trust me that there was a time when scientists were supposed to be objective and fair as possible. That ship has sailed. I will leave it to you to decide whether that is a good thing or not. As for me, I think you have to “pick a lane” either scientific information tries to be objective, or it is a tool in support of advocacy. Anyway, enough history from this Older Person. Here’s a link to a piece by Keith Kloor in Issues in Science and Technology.

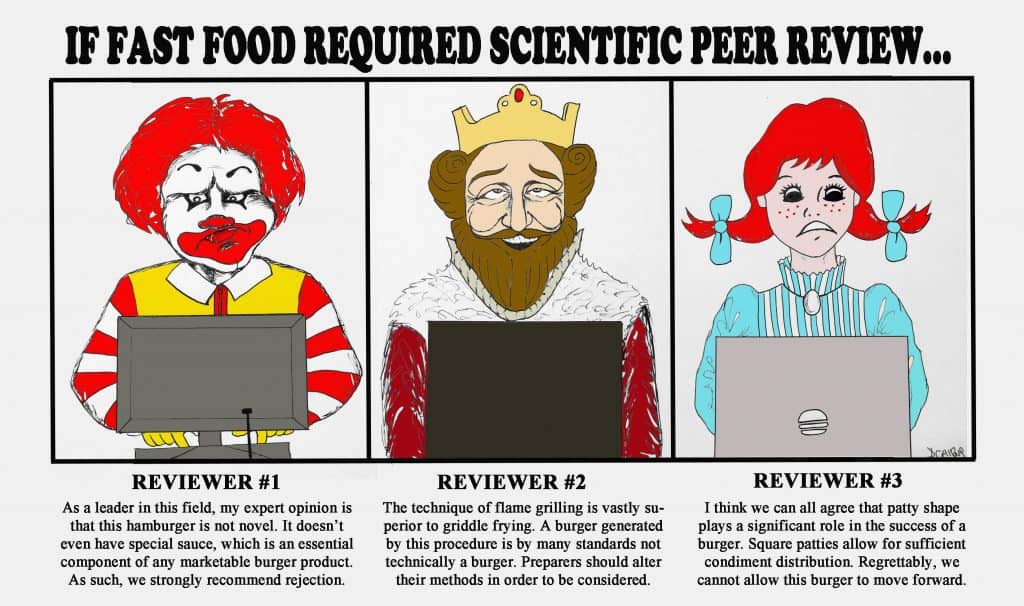

In 2013, Canadian ecologist Mark Vellend submitted a paper to the journal Nature that made the first peer reviewer uneasy. “I can appreciate counter-intuitive findings that are contrary to common assumption,” the comment began. But the “large policy implications” of the paper and how it might be interpreted in the media raised the bar for acceptance, the reviewer argued.

Vellend’s finding, drawn from a large meta-analysis, challenged a core tenet of conservation biology. For decades, ecologists have held that the accelerated global rate of species extinctions—known as the biodiversity crisis—filtered down to local and regional landscapes. This belief was reinforced by dozens of experimental studies that showed ecosystem function diminished when plant diversity declined. Thus a “common assumption” was baked into a larger, widely accepted conservation biology narrative: urbanization and agriculture, among other aspects of modern society, severely fragmented wild habitat, which, in turn, reduced ecological diversity and eroded ecosystem health.

And it happens to be a true story—just not the whole story, according to the analysis Vellend and his collaborators submitted to Nature. In actuality, plant diversity at localized levels had not declined, they found. To be sure, in landscapes people had exploited (for example, for agriculture or logging), habitat became fragmented and nonnative species invaded. But there was no net loss of diversity in these remnant habitats, according to the study. Why? Because as some native species dropped out, newer ones arrived. In fact, in many places, species richness had increased.

The peer reviewer did not hide his dismay:

Unfortunately, while the authors are careful to state that they are discussing biodiversity changes at local scales, and to explain why this is relevant to the scientific community, clearly media reporting on these results are going to skim right over that and report that biological diversity is not declining if this paper were to be published in Nature. I do not think this conclusion would be justified, and I think it is important not to pave the way for that conclusion to be reached by the public.

Nature rejected the paper.

Although it was published soon after by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—without triggering media fanfare, much less public confusion—the episode unsettled Vellend, who is an ecology professor at the University of Sherbrooke, in Quebec. His uneasiness was reinforced when he presented the paper at an ecology conference and several colleagues voiced the same objections as the Nature reviewer.

Vellend discusses all this in an essay that is part of a collection titled Effective Conservation Science: Data Not Dogma, to be published by Oxford University Press in late 2017. His experiences have left him wondering if other ecology studies are being similarly judged on “how the results align with conventional wisdom or political priorities.”

The short answer appears to be yes.

Warning: the rest of the article includes climate science drama.

Thanks Sharon, now I have to figure out how I can beg borrow or steal a copy. An essay by Peter Kareiva and Michelle Marvier did a lot to collect my thoughts on how we “do” conservation and has informed my thoughts ever since. I have to read this.

Som- in our area many libraries have access to Prospector. Here is what they have of Kareiva books

https://prospector.coalliance.org/search~S0?/aKareiva/akareiva/1%2C3%2C12%2CB/exact&FF=akareiva+peter+m+1951&1%2C10%2C

Maybe your area has a similar network of county and university libraries? Your local library might also do an interlibrary loan.

As a person who recently lost my university library privileges as a student through graduation, it would sure be nice if citizen-researchers could pay somehow for access to university collections and databases. It’s kind of ironic that now that databases are available with great search capabilities, in most cases alums can’t access them except on campus. Which can be quite a drive for us rural folks.