It sometimes seems to me that there is a gap between the ideas that laws have enshrined about things.. and the messiness of dealing with the same things in the real world. Species is one of the ideas that seemed most difficult for me, as my experience as a population geneticist was that different disciplines who study different taxa often had their own ways of thinking about them. And hybridization happens.. to geneticists, it’s just another way of generating variation without any negative value associated with them (think jack pine and lodgepole hybrids).

It sometimes seems to me that there is a gap between the ideas that laws have enshrined about things.. and the messiness of dealing with the same things in the real world. Species is one of the ideas that seemed most difficult for me, as my experience as a population geneticist was that different disciplines who study different taxa often had their own ways of thinking about them. And hybridization happens.. to geneticists, it’s just another way of generating variation without any negative value associated with them (think jack pine and lodgepole hybrids).

Trying to explain that shifting world of species definitions has been difficult for me, but this article in New Scientist, I think does it well.

Some excerpts:

Darwin recognised that his ideas posed a profound problem for the way biologists define species. Curiously, though, his work didn’t lead to a reappraisal of the concept. Rather, the “modern synthesis” of evolutionary biology – a mid-20th century effort to pull together Darwin’s work on evolution and Gregor Mendel’s on heredity – saw species as a real and distinct level of biological organisation, as valid as the molecule, cell or organism. The synthesis was so influential that it still shapes the way many of us think of species. It is why we tend not to see them as arbitrary. And it explains the popularity of the biological species concept. “That made it into the textbooks,” says Zachos. And from there into the popular imagination.

(and from there into law..)

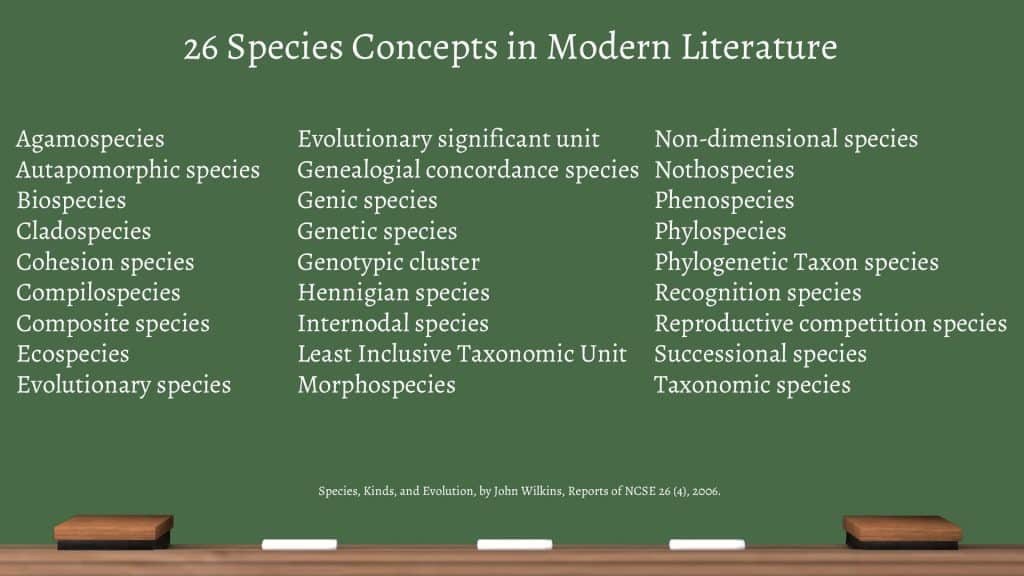

Behind the scenes, however, a different story was playing out. In the past century, scientists have redefined what a species is time and again, heaping confusion upon confusion (see “Parsing nature”). Zachos identifies no fewer than 32 competing definitions in his 2016 book on the subject, Species Concepts in Biology, and notes that two more have been added since then. This partly reflects the distinct ways that researchers in different subsets of biological science see the living world. Ecologists, for example, focus on environment, resources and adaptations, whereas palaeontologists are more interested in the shape of the fossils they study. It also reflects developments in science, with advances in genetics now making it possible to decode the DNA of individual organisms and reconstruct family trees. The upshot is often acrimonious, with players championing their favoured species concept while simultaneously taking pot-shots at rival ideas.

Specious arguments

The profusion of definitions also causes practical problems because different types of biologists use different species concepts. Put simply, an insect species might not be equivalent to a mammal species or a flower species – even though most of us assume they are. “A lot of research is based on counting species,” says Zachos. “It’s as if we think we’re all using US dollars, but in reality we’re lumping together Japanese yen, euros, US dollars and pounds.” (my italics)

These problems are exposed whenever researchers change their definition of species – something that is happening increasingly often. For instance, in 2011, some biologists studying hoofed mammals shifted from a biological species concept approach to one based on heritable differences. Instantly, the number of species in the group rose from 143 to 279. Zachos and others worry about the consequences of such “taxonomic inflation” for conservation. Inflation, he points out, is often associated with a devaluation of the currency. Society might care a little less about losing a few species to extinction.

It’s a very complex idea, ever-shifting, linked to a legal structure somewhat more difficult, or impossible, to shift. Hence tension.

A new flare-up in the war between the ‘Lumpers’ versus the ‘Splitters’?

The other day I was wondering if the bard owl isn’t better than no owls.

The question of what is a “species” comes up fairly often under the Endangered Species Act, where challenges to listing a species have been based on arguments that it isn’t a separate species. The law actually defines “species” for its purposes to include “subspecies” (which no doubt begs the same question) and some other language that ties to “interbreeds when mature.” The Forest Service Planning Rule does not define “species” for the purpose of protecting “species of conservation concern.”

The reason for why you should care about something being a species is important. Endangered red wolves reintroduced in North Carolina may be a result of hybridizing with coyotes (that could have been caused by human-induced low wolf populations), but should that disqualify them from protection if they otherwise fulfill a missing ecological role? Coyotes in Texas have been found to contain red wolf genes that do not exist in any living red wolves. Should we actually be concerned about endangered genes?