I don’t know if you have been following the 1619 Project. It is a major initiative from The New York Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to “reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.” The terms “original sin” have been used. But to my mind, there is one more fundamental underlying sin that pre-dates slavery. If one has to be “original,” this one would be it. That is the theft of land and mistreatment of Native peoples.

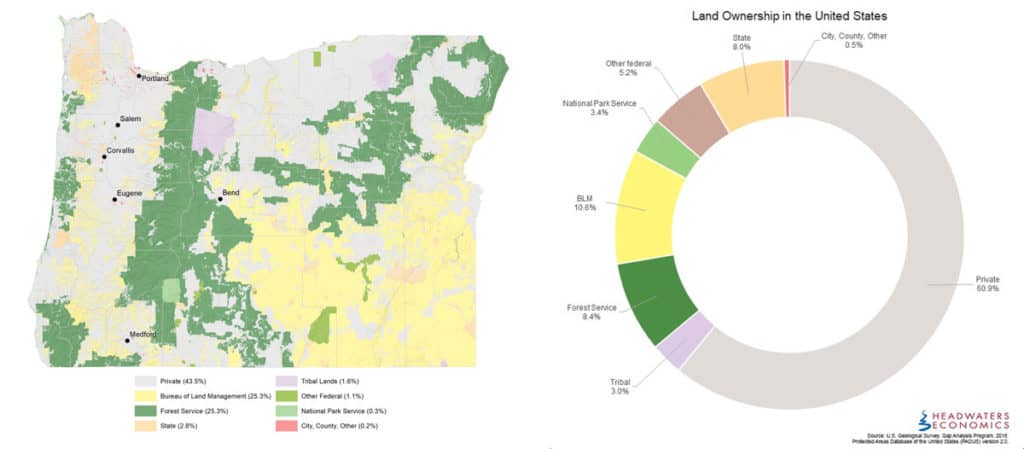

What can we do about this history? One idea is to return some current public lands, usually Forest Service or BLM, to the original owners. In my view, this idea is compelling from a justice perspective. Certainly there are a host of details that could be puzzled over, debated, and negotiated. Some might include ideas about 1) how much, 2) where, 3) who decides, 4) what commitments to current uses and access, 5) should lands be selected based on treaty status or other criteria (sacred sites or ?), 6) what kind of a transition period. In the same way that companies and states can commit to zero carbon by 2050, which will require a major social and technological transformation with environmental goals, could we perhaps set the same target for repatriation of public lands for justice goals? Say “Repatriate by (20)38”? There is an argument to be made that under our current non-Native management, the private sector spends much money on debating, communicating and litigating with others about public lands management, and those same funds could potentially instead be spent on purchases, easement and incentives on private land. Each group could then determine exactly which uses or protections it wanted. Perhaps less fighting over conservation, and more conservation.

Here’s an article in High Country News from August of this year It tells the story of some Oregon Tribes’ efforts to get public land returned (including trying to buy the Elliott State Forest).

Conservation groups, critical of Lone Creek’s forestry practices, staunchly opposed its involvement and accused the partnership of wanting to privatize the forest. Conservationists in turn were called out for their failure to work with tribal nations: “Your organization has mobilized opposition to the sale, with little to no engagement with the Tribes who would have, once again, become the stewards of this land,” a consortium of racial justice groups, including NAACP Portland, wrote in an open letter to the Sierra Club, Cascadia Wildlands and four other conservation organizations. “We also note the many ways in which environmental groups in Oregon remain predominantly white, and work from a place of white privilege; this situation is a very clear example of the lack of racial justice analysis applied to what is a complicated situation.” Then-Sierra Club Oregon Chapter Director Erica Stock responded, “As an environmental conservation community, we must do more to proactively reach out to Tribal Nations and rebuild trust.”

Ultimately, the sale was dropped by the state after intense public outcry, but tensions between conservation groups and tribes remain.

“The conservation movement began as a way for settlers to justify the seizure of Indigenous lands under the pretext that Native peoples didn’t know how to manage them,” says Shawn Fleek, Northern Arapaho, who is director of narrative strategy for OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon. “If modern conservation groups don’t begin their analysis in this history and struggle to address these harms, it becomes more likely they will repeat them.”

Meanwhile Andy Kerr, who worked for two decades at Oregon Natural Resource Council (now Oregon Wild), still objects to public lands becoming tribal lands. “The Democrats who supported this legislation came down on the side of Native Americans and, in this case, against nature,” Kerr wrote in a December 2018 post on his website.

While “Native Americans” should get some form of compensation, Kerr argued that “such compensation should not come at the cost of losing federal public lands of benefit to all Americans.” Both Runte and Kerr see money as an adequate substitute despite treaty law, since “in the society that won out in that struggle for a continent, the most common way to right wrongs is by money being transferred to the aggrieved parties from the parties that unjustly benefited.” Kerr continues: “The currency of compensation by the United States to Native American tribes ought to be the currency of dollars, not that of the irreplaceable and precious public lands that belong to all of us.”

But it’s not a matter of money, says Cris Stainbrook, Oglala Lakota, of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation. “It’s ironic they don’t recognize they’ve had the public benefit of lands for on the order of 165 years of using someone’s land that was guaranteed to them, and used those lands to their own benefit. It’s about time, after 165 years, that they live up to the treaty.”

For folks interested in Alaska, here is an HCN WaPo op-ed critique on the Natural Resources Management Act of 2019 with the tagline “A nation of laws cannot exist on stolen land.”

On October 11th, 2019, an interesting article was published which in the MIT Press Reader by journalist Mark Dowie who is former publisher and editor of Mother Jones magazine. He authored thel book, “Conservation Refugees,” from which this article is excerpted. The title and subtitle are as follows:

“The Myth of a Wilderness Without Humans”

For over a century, conflicting views of wild nature created a rift between indigenous people and misguided conservationists. At least this seems to fit Sharon’s post. It is interesting how most of those historical holy men who established today’s wilderness cult following like John Muir, Ansel Adams & other photographers created the original myth about what wilderness was/is through their deliberate photography which fabricated the narrative which still lives on in the minds of the diehard activists today who pursue this rewilding mission which often excludes most human beings other than themselves who are exempt from the harsh rules.

https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-myth-of-a-wilderness-without-humans/

–

See also:

Yakama, Lummi nations: Remove Columbia River dams

https://www.yakimaherald.com/news/local/yakama-lummi-nations-remove-columbia-river-dams/article_758440e6-77ab-5fdd-930b-d0a61c991bc8.html

CELILO VILLAGE, Wasco County, Ore. — The Yakama and Lummi nations called Monday for taking down the Bonneville, The Dalles and John Day hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River to restore salmon runs that were once the mightiest in the world….

JoDe Goudy, chairman of the Yakama Nation, and Jay Julius, chairman of the Lummi Nation, gathered — on Indigenous Peoples Day — at Celilo Village, all that is left of the fishing and cultural center at Celilo Falls, the most productive salmon fishery in the world for some 11,000 years. The falls were drowned beneath the reservoir of The Dalles Dam in 1957.

Goudy said Columbus Day, a federal holiday also on Monday, celebrates the invasion of the lands and waters of indigenous people under the colonial doctrine of discovery, under which Christian Europeans seized native lands.

The lower Columbia River dams inundated many usual and accustomed fishing sites of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and led to the decline of salmon, lamprey and other traditional foods.

“The tribe never consented to the construction of the lower Columbia River dams,” said Goudy, wearing an eagle feather headdress and white buckskins. “On behalf of the Yakama Nation and those things that cannot speak for themselves, I call on the United States to reject the doctrine of Christian discovery and immediately remove the Bonneville Dam, Dalles Dam and John Day Dam.”

Then there’s this: https://www.mtpr.org/post/racism-distrust-permeate-bison-range-management-debate

“In 2016, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages the Bison Range said it supported a bill drafted by the CSKT to transfer the refuge from the Service to federal trust ownership for the tribes. That drew a lawsuit from a group called Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. It claimed the government and tribes didn’t do enough environmental assessment of the proposal. Shortly after that, then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke reversed the Fish and Wildlife Service’s endorsement of surrendering management of the Range to the tribes.” (And yes, racism is part of this story, too.)

I think there are things that could be done in the way of co-management (something Tribes have asked for and not gotten) that would fall short of a title transfer, but address most of the needs of Tribes for traditional uses. I would even be open to considering transferring all management responsibility, if it remained subject to federal public land law, and included general public access.

The quote from Shawn Fleek is provocative and not intuitive (to this white man any way). Or as put by another blogger: “This is an interesting take on frontier justice, for while conservationists were indeed complicit in accepting the status quo that followed removal of Native peoples, given the opposition from locals to withdrawal of lands from private use, it seems a reach to imagine gold miners triggering armed conflict under the banner of conservation.”