Thanks to Shawn Regan of PERC for sending in these two pieces relating to funding for LWCF and the Great American Outdoors Act, related to my previous post here that dealt with the impacts of a possible Biden policy of “no new oil and gas leases” on LWCF.

The first is by Jack Smith, titled “How Will We Pay For the Land and Water Conservation Fund?”

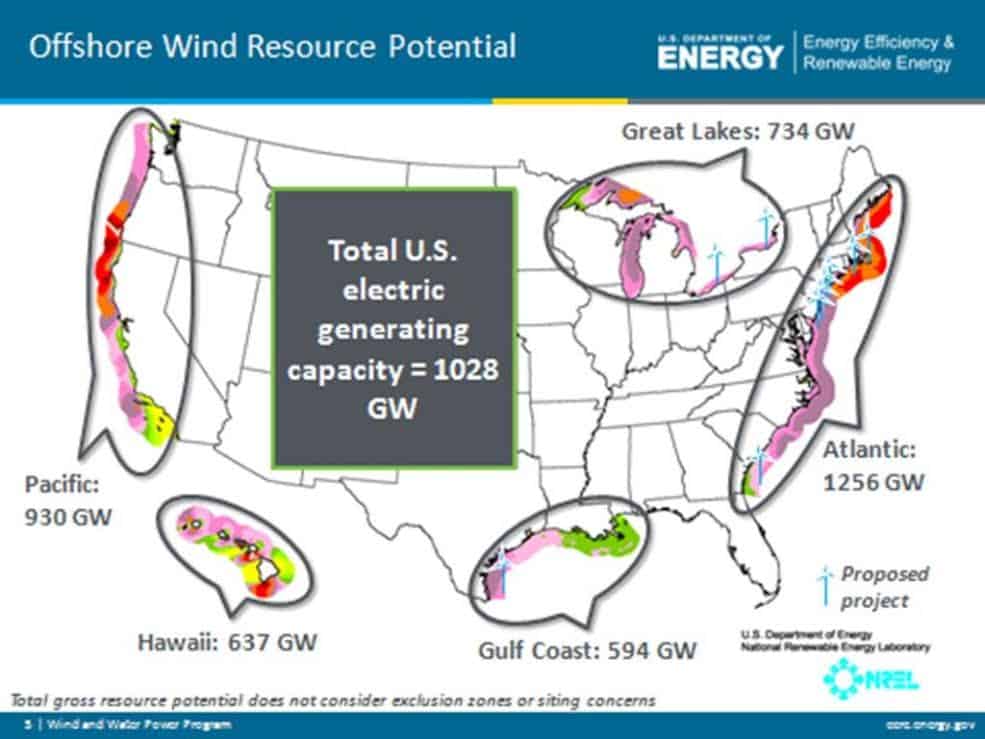

How much federal revenue could offshore wind generate? The technical energy potential of winds off the U.S. coast is titanic—about 2,000 GW, or nearly double the amount of energy the entire country uses today. But the latest projections suggest that it will take a long time to realize offshore wind’s potential, so funding for the LWCF will probably depend on oil and gas revenue through at least 2050.

To see why, it’s important to understand the different fees energy developers pay the federal government to develop offshore energy resources. These are the revenues that currently sustain the LWCF and a myriad of other funds and programs.

First, developers bid for leases to tracts of property in auctions held by a federal land agency—in the offshore context, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Whichever company wins each auction pays the winning bid—called a “bonus bid”—and then begins paying rent on the number of acres in their lease. Once a developer begins to produce and sell a resource from their lease, they pay the federal government a cut of every unit they produce, called a royalty.

Of these three revenue streams that fund the LWCF, royalties are by far the largest. In 2019, offshore fossil fuel energy royalties totaled $5.0 billion, 84 percent of the total $5.9 billion in offshore energy revenue. Bonus bids and rental payments together provided the other 16 percent.

Offshore wind royalties so far have generated zero dollars, since no project is far enough along to generate energy. But in theory, such projects could generate huge returns in the long run. At the current royalty rate of $5,010 per MW, harnessing all 2,000 GW of technically recoverable offshore wind energy would generate more than $10 billion per year in royalties. Building that much wind capacity is far beyond America’s foreseeable needs, grids’ load-balancing capabilities, and any realistic time horizon. But in the long run, it sets an upper bound for royalty revenue.

So it looks like wind energy probably won’t single-handedly fund the LWCF for at least 30 years, which means that the Great American Outdoors Act will continue to rely in large part on oil and gas revenue.

As a result, it’s clear that fully funding the LWCF permanently will present challenges. Fossil fuel development is increasingly under attack due to concerns about climate change. As policymakers seek permanent funding for conservation and recreation, the challenge will be to find other, more dependable funding sources to sustain outdoor recreation and conservation…

Issues with O&G royalties are legion… 1) the royalties are generally ridiculously low in terms of the market value of the carbon resource and the costs to the env. The public is getting screwed if you think about how much O&G is extracted from fed lands and reserves. 2) virtually nothing is being paid into any kind of national fund to replace carbon sources with renewables in the form of research and incentives. 3) Total $ deposited in LWCF has generally been sufficient but Congress typically appropriates only a small % of total authorization; usually due to conservative opposition to creating more federal land. The promise of LWCF is mighty, delivery is far short of potential.

Jim, there are many incentives, and much research ongoing on renewables outside of royalty funding. What is interesting to me is that renewable industries and their supporters do very well at getting incentives and research through the standard federal budget process. FS and Park upkeep and deferred maintenance not so much. I wonder why that is.. not enough advocacy by interest groups? Inherent lack of sexiness of … deferred maintenance, even compared to acquisition?

It would be interesting to get a Congressperson’s view on this, but I don’t know any well enough to ask.

Point taken. But if you look at the ENORMITY of the issue — climate change, carbon fuels, renewables — the legacy of tax breaks for the O&G industry and the lack of “Marshall Plan” type effort to convert to renewables, I still say MORE is needed, much more.