Recent posts in this blog have advocated cessation or reduction of logging as a cure for poor water quality, erosion and other problems that may occur with timber harvesting. The three decade nationwide decline in timber harvesting on our national forests has been a long-term test of the validity of this proposal. This de facto experiment has revealed the critical need for more active management of the timber resource.

While this 30 year decline occurred nationwide, the impacts have been most severe in the West.

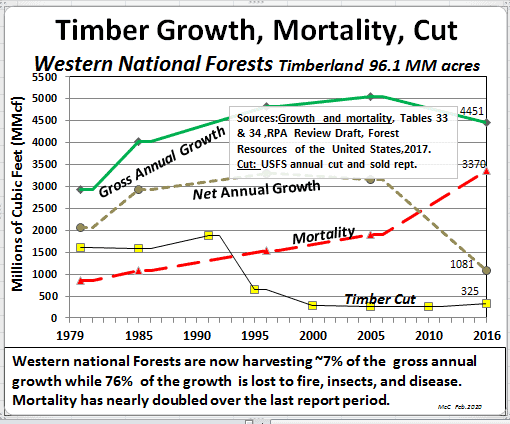

Figure 1 graphically depicts the changes that occurred on western forests during this period of limited harvest.

In the west in the early 1990s the United States Forest Service was cutting about 40% of the growth while 30% died.

In 2016 the USFS in the west cut 7% of the growth while 75% died.

Fig. 1

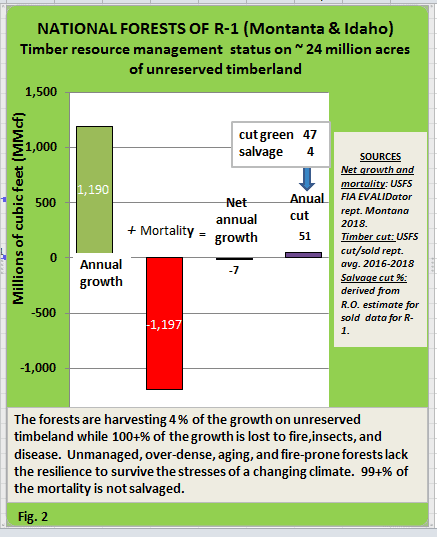

Figure 1 tells its story clearly and succinctly. On a more localized scale, Figure 2 reveals the recent condition of the timber resources in the Northern Region of the U.S. Forest Service (R-1). It is an example of the how this involuntary virtual shut-down of logging is playing out in the real world.

The results are clear: a tiny cut, massive mortality, and negative net growth.

The enormous economic and social impacts of this operational shift have been documented extensively elsewhere.

However, the effect of widespread tree mortality on climate change often is overlooked. The large reduction in oxygen producing leaf area plus the addition of a huge volume of decomposing (CO2 generating) dead trees only can accelerate this unfolding global calamity.

The solution to these problems is not less management but better management: the universal use of Better Management Practices and the corrections of the many causes of management impotence.

Among the most frequently cited of these causes are:

- under-funding

- over-regulation (a tangle of shifting, restrictive, unclear, and often conflicting laws, regulations, executive orders, written and unwritten policies, and judicial mandates)

- serial litigation

- over planning and analysis (appeal-proofing proposals and reports)

A combined effort by timber interests, the environmental community and the USFS aimed at removing these impediments could be a productive strategy moving towards prudent husbandry of our public lands.

Logging opponents are urged to study the charts and consider their implications. Comments would be welcomed.

Well done, Mac! It would be interesting to see these data and charts for conditions in each decade going back 50 or more years, to compare trends over time.

Who is Mac McConnell?

He worked for the US Forest Service for 30 years, I think, including district ranger.

Has he continued to work after leaving the Forest Service and if so, for whom?

As far as I know, Mr. McConnell is an independent consultant. Here’s another bio, from a 2018 op-ed from the Tallahassee Democrat….

https://www.tallahassee.com/story/opinion/2018/03/01/opinion-change-ahead-apalachicola-national-forest/384380002/

W.V. (Mac) McConnell is a retired (1943-’73) U.S. Forest Service officer, former timber staff officer for the National Forests in Florida, and past chair of the N.F.s in Florida Resource Advisory Committee. He has participated in and observed the management of national forests for 72 years.

An guest column written by Mac in 2018 had this bio:

W.V. (Mac) McConnell is a retired (1943-’73) U.S. Forest Service officer, former timber staff officer for the National Forests in Florida, and past chair of the N.F.s in Florida Resource Advisory Committee. He has participated in and observed the management of national forests for 72 years.

Thanks, Steve and Matthew, I should have posted that. I believe he does consulting work, and hopefully he will comment.

Hello Michal,

I’m glad you asked and I apologize for the delay in replying. W.V.(Mac) McConnell, Forester and Land Use Planner, holds MS degrees in Urban and Regional Planning and Sociology. He is a retired Forest Service timber staff officer (1943-1973) and has spent his 47 post-retirement years as a consultant, primarily in energy biomass management. Brief stints with a state planning agency, publishing in several peer-reviewed journals and an edited volume and serving as chair of the NfS in Florida RAC round out his credentials

A sincere ”thank you” to my friends who covered for me (their efforts follow.)

It seems to me that the large timber harvests during about 1960-1990 have given us very different forests, during 1990-2020. Thus, the comparisons are not all appropriate. In particular, harvests from the earlier decades have produced abundant early-succession stands, with high tree densities, especially in some types, in which many trees are going to die. Thus the trend in tree mortality can be argued as being due to past logging, not due to current lack of logging. Moreover, this analysis is based only on trees, echoing the idea that a “healthy forest” is only “healthy trees”. Obviously, it neglects very many issues, climate change and growing human needs for outdoor recreation, declines in rare wildlife, among them.

Indeed, it’s difficult, if not impossible to compare one type of apples to one type of oranges.

On one old Ranger District, we did 65 million board feet in a year, with clearcuts and overstory removal. Currently, they harvest 5.5 million board feet in thinning projects per year. There are too many differences to make any kind of valid comparison. We cannot even compare them to pre-human conditions or different climates.

With regard to Figure 1, the comparisons made between 1990 and 2016 were of an identical metric: cubic feet. The fact that the forest had changed its condition or that the public perception of management priorities had shifted had no influence on the nature of that metric. Comparison between the two volumes is certainly valid. Have I missed something?

The contention that 75% mortality in 2016 (Figure 2) was caused by logging prior to 1990 seems a bit off-lline. Could you cite data supporting this opinion?

I find it unlikely that millions of dead trees in the forest will benefit outdoor recreation and rare wildlife or counter climate change. Am I mistaken?

The slope of the mortality line increases while the net growth line decreases after2005. Changes in timber harvest levels happened in the early 1990s. There doesn’t seem to be a compelling reason to connect these two events, which are spatially separated by about 15 years. Correlation doesn’t equal causation, but in this case, the trends don’t show obvious correlation, unless we have a mechanism that predicts that decreased timber harvest will cause tree mortality with a 15 year time lag? There are widespread reports of increasing tree mortality around the world and in the western US, particularly in arid and semi-arid forest types, which fits much of region 1. Many are tied to extreme climate events – i.e. see https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ecs2.2455

You’re correct. It is probable that the proximate cause is climate change. Each year the results of non-logging (dense, older,less resilient timber stands) becomes more evident . Each year the temperature rises and climate change impacts become more severe. The cumulative impact results in the deferred mortality which is now taking place. Without remedial action at both levels) (reduced emissions and more intensive management) the death rate will continue to increase.

I totally respect my elders, Mac, but I’m also very glad that your old-school notions of forest ecology and forest ecosystems aren’t nearly as prevalent as they might have been when you retired from the U.S. Forest Service almost 50 years ago.

Your claims may or may not be correct, but the evidence you present doesn’t support any of them.

You’re correct in that climate change is a probable proximate cause along with non-management.. Each year the results of non-logging becomes more evident (denser, older,less resilient timber stands) . Each year the temperature rises and climate change impacts become more severe. The combined cumulative impacts result in the deferred mortality which is now taking place. Without remedial action at both levels (reduced emissions and more intensive management) the death rate will continue to increase. The root cause, of course, is human population ( 7.9 billion and increasing at the rate of 224,000 per day) that has probably already surpassed the earth’s carrying capacity.

From my own experience (in the west but not in Montana), much tree mortality has been tied to bark beetles.. some of which happen due to drought but mostly because the trees are old, especially lodgepole. How did they get to be old? Because the stands got started 100 or more years ago. How? Possibly a large fire, logging or ?? Remember Leiberg in the early 1900s was still seeing the effects of Native American burning.

This is one of those areas in which I think it’s better to frame the problem of tree mortality (little trees in the understory? Big old trees?, and start at the stand level and work your way up rather than the satellite view. I’d start with forest entomologists and pathologists.

Meanwhile, also in USFS Region 1….

According to Mike Bader, the Lolo National Forest advertised 3 timber sales today, falling under the category of Small Business Administration sales, which allows the bidder to request the U.S. Forest Service to construct permanent roads. Does anyone know more about this?

I searched on Soldier Blue Timber Sale on Google in quotes and it went to the Lolo website. From there I looked at projects https://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=50777 and found this link to a Soldier Blue Butler Project. By name, I guess they are the same project.

It’s kind of shocking, isn’t it Mac, to think we even HAD forests in the American West before the arrival of logging?! I mean, without logging to liquidate annual growth, and convert all that worthless natural forest to young thrifty plantations. OMG the horror! I lived a career in (and contributed to) the overly ambitious, well-intentioned FS timber craze of the late 20th century. The consequences have been well chronicled, beginning with the Bolle Report of abuses on the Bitterroot NF. I don’t want to see the FS go back there, even though it is possible to achieve annual harvests at rates more comparable to growth.

I believe the key is targeting ECOSYSTEM HEALTH as a raison-d’etre for cutting timber, rather than producing wood products (see my memoir Toward a Natural Forest). The whole forest will be better off and, yes, products will flow — though likely not as much as when trying to regulate a wild landscape for timber industry. In my experience, the environmental community (that many like to scapegoat) is quite reasonable if the purposes and methods of timber harvesting are sensitive to the legitimate constraints of the forests in question.

The FS will never log their way out of this conundrum.e

We can debate the causes, but I’m more interested in the implications for management: “However, the effect of widespread tree mortality on climate change often is overlooked. The large reduction in oxygen producing leaf area plus the addition of a huge volume of decomposing (CO2 generating) dead trees only can accelerate this unfolding global calamity. The solution to these problems is not less management but better management…” What about the science regarding the relative CO2 benefits (short and long term) of “managed” vs “unmanaged” forests?

That’s the problem I’ve had with the carbon studies. They take an area, assume some form of “management” (which as we know could mean a zillion different things) then make assumptions about whether or not fires will burn up the trees, or they will die from something else, instead of continuing on for a hundred years or so (?) depending on the species. Then there’s the whole thing about using trees removed for various energy or building purposes. After years of reading this stuff, all I can say is “the answer depends on a specific area, definitions of management, and then a lengthy series of assumptions.”

Including the fact that we hear that due to climate change wildfires will burn everything up anyway, and our ancient forests will die from drought… Again, the only two honest answers IMHO are “we don’t know” and “it depends.”

Hi Guys

I had hoped that my effort would stir up some controversy but was was pleasantly shocked by numbers. Surprising to me was the fact that the comments were mostly about my interpretation of the charts. not a word about the graphics themselves. They are full of facts that deserve discussion. What are your thoughts on Figures 1 and 2? How do you interpret them?

The discussion of mortality in recent comments piqued my curiosity with the following results. 74% of total deaths occur after age 100. The table confirms Sharon’s feeling that age is a key factor in death (just like humans), especially for Lodgpole pine

.

Mortality for R-1 (Montana & Idaho) unreserved timber land

by century age classes

Stand age MM Ac. MMcf cf/Ac. % of MMcf

class

0 -100 13.5 313 23 26%

101 – 200 9.3 496 41 41

200-500 1.4 388 32 33

Totals 24.2 1197 100%

The several references to tree age and mortality in recent comments prompted some research with the following results. The key finding is that only 25% of deaths occur during the first 100 years of stand life.

Mortality for R-1 (Montana & Idaho), by century age classes

Age class MM Ac MMcf MMcf per Ac. % MMcf

0 -100 13.5 313 23 26

101-200 9.3 496 41 41

201-500 1.4 388 277 33

Totals 24.2 1197 100%