I thought this storyin the Denver Post was interesting. It raises a question, though, we don’t really know why populations are declining, but the lawsuit from Western Watershed seems to be about grazing. This is not surprising, since that seems to be something WW doesn’t like. For whatever reason, WW doesn’t seem to have the point of view of many (at least in Colorado and Wyoming) that losing public lands ranchers also means losing the home ranch, and the home ranch then tends to become housing developments. And residential development is another threat to the sage grouse.

Grazing as a direct cause of the recent decline seems unlikely Grazers have been grazing maybe since the 1870’s and we can imagine that practices have improved through time. So apparently grazing and GSG have coexisted for the last 150 years. Here’s a story in the Crested Butte Journal about ranching in the valley. So why stop that if it’s not the cause?

If other things (known and unknown) are responsible for the decline (we are talking since the 70’s) why target grazing in the lawsuit? Will it actually help the bird? We don’t know, since we don’t know why it’s declining. For a while, as you can see, since 2005, the collaborative groups and ranchers seem to have made an impact.

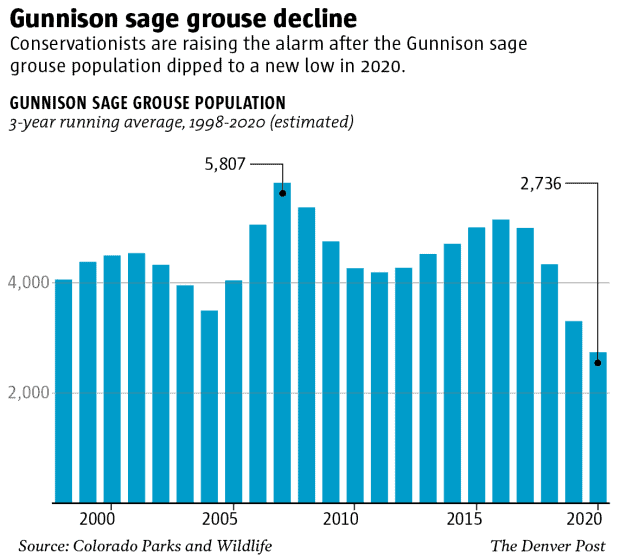

CPW provides these population estimates:

In the years after it was named a new species, millions of dollars were spent on conservation efforts. Gunnison County hired a sage-grouse coordinator in 2005. The federal government paid for aerial seeding to provide food for the grouse and changed their mowing practices to cater to the bird. In 2014, the species was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The Gunnison sage grouse numbers increased between 2004 and 2007, and annual counts of the males at the breeding grounds have shown the total population hovering between about 4,000 and 5,000 since then — until 2018, when the numbers began to plunge.

The total population was estimated at 3,500 in 2018, 2,100 in 2019 and 2,500 this year, according to data provided by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

It could be part of a cyclical decline, a temporary dip driven by drought and two tough winters, but with so few birds left and with their habitat continually shrinking, the drop has raised alarm bells for conservationists, and for Braun.

Still, efforts are underway to protect the birds, said Jessica Young, who pushed Braun to recognize the birds as a separate species when they worked together beginning in the 80s.

“Since I live in Gunnison and make my life in Gunnison, I see day in and day out how hard people are working on the issue,” she said. “What he sees from the outside is the numbers, and the decline and the small populations literally starting to wink out. So we see two different worlds. I’m deeply concerned about them. I absolutely consider them imperiled….but I might have a bit more hope because of how hard I’ve seen people try.”

It’s interesting how Jessica Young talks about “different worlds”; it’s something I’ve heard quite a bit with these kinds of controversies. We’ll be discussing this more when we get to The Battle for Yellowstone.

In early December, the Center for Biological Diversity and Western Watersheds Project filed a lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, alleging that the federal agencies have failed to do enough to protect the Gunnison sage grouse.

The lawsuit, one of many over the years, takes aim at the amount of grazing that is allowed on publicly owned sage grouse habitat, arguing that the grazing is harming the birds by destroying vegetation they rely on, limiting their ability to breed and hide from predators.

“Ultimately the bird is critically imperiled and something has to change,” said Talasi Brooks, staff attorney at Western Watersheds. “Maybe it’s taking cows off the land, maybe it is changing the season of use…but one way or another, any movement toward actually doing something about the threat of livestock grazing to the sage grouse would be a good thing.”

It sounds like ranchers and the BLM and other cooperators, have, indeed, been assiduously doing things.. and they seemed to be working, but took a sudden downturn associated with heavy snow years. It seems to me that it’s another case where we don’t really know why populations are declining, but litigators round up the usual suspects that they don’t want around. Using lawsuits as a policy tool in this case can 1) place the pain on certain groups that the litigatory groups don’t approve of, and 2) placing the power to place that pain outside the hands of local people (justice question), and 3) having policy with impacts on folks’ livelihoods determined in settlements behind closed doors, without knowledgeable on the ground people, nor the public involved (both a justice and “are you getting the best information to decide” question).

It can effectively cut local people and their knowledge out of the decision-making process, which has serious justice implications IMHO. It can also simply not work for the species, as the target groups may not be the cause of the problem, and these changes could possibly make things worse for the bird.

Hi Sharon. I work for Western Watersheds Project (WWP) but I’m not an attorney on this particular lawsuit. However, the complaint WWP filed clearly recognizes that residential development is one of the top threats to Gunnison sage-grouse. But the Fish and Wildlife Service has also acknowledged that livestock grazing adversely affects this particular species. Whether those adverse effects rise to the level of jeopardy to the species’ continued existence (operative language from the ESA) is at the heart of the lawsuit.

Here is a link to the complaint. You might have to copy/paste, I don’t know how to make URLs hyperlinks here.

https://www.westernwatersheds.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Compl._GUSG-CCA-BiOp.pdf

You note that domestic livestock grazing has existed on the landscape for 150 years, and likely at more intense levels in the past. But that is not really relevant to whether continued livestock grazing at current levels adversely affects (which FWS admits) or jeopardizes the species (as WWP contends in its complaint). The species has already lost a lot of its range, so any additional loss of occupied habitat or numbers pushes the bird closer to extinction.

It’s true that much of the remaining range of the Gunnison sage-grouse is on private land. But a greater amount is on Forest Service, BLM, and Park Service lands.

You can see the bird’s range at this link if you scroll down a bit from the top. It can take a while for layers to load.

https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/6040

You can see land ownership on this BLM Colorado interactive map. Again, it can take a while for layers to load:

https://blm-egis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=59bfb9b9406d4a409e2f510bda9e409f

Table 1 in the Federal Register notice of the bird’s 2014 listing as threatened breaks down land ownership in the species’ occupied habitat by population. Also note p. 69204 discussing the dramatic loss in range size, from 21,375 square miles historically to 1,822 square miles in 2014 at the time of listing:

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2014-11-20/pdf/2014-27109.pdf#page=1

You imply that restrictions on livestock grazing to protect Gunnison sage-grouse will cause private home ranches to be sold for housing subdivisions, thus we should not try to protect this imperiled species from one of its main threats on the majority of its range (public lands). I don’t think such direct causation can be made between sage-grouse protections on public lands and subdivisions on private lands. If you have more than anecdotal evidence of one leading to the other on specific private parcels, I’d be interested to read it.

There are tools and methods available to address residential development on private land in the Gunnison Valley. Gunnison County has a Land Use Resolution meant to consider Gunnison sage-grouse habitat. I have not researched how well it has worked to slow or prevent development of grouse habitat, but here is a link to it:

https://www.gunnisoncounty.org/DocumentCenter/View/3157/Gunnison-County-Land-Use-Resolution–Amended-August-2020?bidId=

WWP uses various available tools, including litigation when necessary, to urge federal agencies to fulfill their statutory mandates regarding wildlife and habitat on public lands. Should livestock grazing at levels that contribute to the Gunnison sage-grouse’s further decline be allowed to continue because any additional restrictions might be economically unfavorable for certain ranchers? That seems to be your perspective, but that’s not what Congress intended when it passed the ESA.

John, thanks so much for the links to the maps and to the county land development restrictions, which seem very impressive. (others, you can find them on these six pages) https://www.gunnisoncounty.org/DocumentCenter/View/1347/Development-in-Gunnison-Sage-Grouse-Habitat-Information-Sheet

My point was that ranchers have been there for a long time, conceivably with less grouse-friendly practices. The collaborative got started in 1997 apparently 24 years ago. https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/plan_documents/tcca/tcca_672.pdf

Something bad started happening in 2018. We don’t know why. Yes, apparently the law says to ratchet down everything that might impact the species, even if the problem (e.g., white-nose syndrome, climate change) is not related to those practices or activities. Or even if we have no clue what the problem is, or whether these changes will be successful at protecting the bird. It seems like certain people will suffer for a public good, when they have done their best (as Jill says above) and we’re not sure that it will work. I get that ESA says that.. it just seems like structural injustice to me. Maybe spread the pain by compensating these folks for the changes?

“Economically unfavorable” may mean they can’t survive. I know I don’t know, I think you don’t know, and I really doubt if the attorneys in the room for DOJ and WW will know.

It does seem, from the WW website, that your group think that “ranching is one of the primary causes of native species endangerment in the American West; it is also the most significant cause of non-point source water pollution and desertification.” It sounds like your group thinks that if you took off all the cows, native species would be fine.. and yet, there are other folks who claim that the greatest threat is recreation, climate change, or non-native species, residential development, or oil and gas or windfarms or….

“I don’t think such direct causation can be made between sage-grouse protections on public lands and subdivisions on private lands. ” Perhaps not for sage grouse, but there is a relationship

between public lands grazing and the viability of the home ranch, recognized in many quarters e.g….https://www.trcp.org/2019/06/05/public-land-grazing-important-american-west/

A couple further thoughts. The article notes that Dr. Braun estimated there were as many as 10,000 Gunnison sage-grouse in the 1970s. There are only 2,700 now. Dr. Braun indicates he knew even as he identified the separate species it would likely be considered threatened or endangered. So the “ranchers have been here a long time” argument doesn’t really offer evidence that livestock grazing has not contributed to the species’ decline. The 1970s are now nearly a half century in the past. The snapshot of data available in the chart does not absolve current grazing practices of any role in the bird’s long-term declining trend. Impacts accumulate over time. And the smaller the remaining populations get, the more quickly they can blink out in the face of on-going threats.

It sounds like you are saying that if addressing one piece of a complex problem does not solve the whole problem, and there might be negative economic consequences, we should not take action. Again, the ESA does not work that way, as you recognize, nor do we have the luxury of time to wait for only economically neutral or beneficial solutions to materialize when a species’ continued existence is in jeopardy.

Jessica Young is quoted in the article saying people have worked hard on the Gunnison sage-grouse issue. But the article does not describe any grazing practices that have changed to better protect habitat or prevent losses – season of use, stubble height requirements, etc. So it’s hard to gauge from this article whether ranchers or federal land managers have taken measures to address the adverse impacts grazing poses to the species.

Yes, Western Watersheds Project recognizes the science that shows livestock grazing degrades wildlife habitat and decreases native biodiversity, pollutes water, and leads to desertification in many instances. I do not believe our website states that “if you take off all the cows, native species would be fine.” We recognize other threats to native species, but livestock grazing is the most pervasive human use of public lands. Notably, livestock grazing impacts will likely exacerbate the negative effects of climate change, particularly if numbers and seasons of use are not adjusted as drought becomes the norm. Also, domestic livestock are one of the main vectors for the spread of non-native species. Many vegetation treatments also result in seeding of non-native species. So some of the other threats you identified are directly inter-connected with livestock grazing.

As for structural injustice, it should not be a surprise that the public lands ranching industry is generally quite well-connected and politically powerful. Livestock associations routinely intervene on behalf of ranchers in public lands and ESA litigation, often represented by non-profit legal foundations. The industry has also initiated litigation against regulation many times in the past.

There has been a rider inserted into omnibus spending bills for many years prohibiting the Fish and Wildlife Service from taking action on listing the greater sage-grouse pursuant to the ESA. FLPMA has been permanently amended to grant BLM and USFS vast discretion on when to undertake new NEPA analyses of grazing allotments, meaning ten-year permits can be renewed on their previous terms and conditions repeatedly without thoroughly addressing new data, science, or changing climate. The very modest protections for sage-grouse in the 2015 plan amendments were quickly set aside by the Trump administration. These actions were not taken in a vacuum – the livestock industry wanted them and got them. It is not yet known how the Biden administration will approach these matters.

Finally, regarding restrictions on public lands grazing and subdivisions, I am familiar with the talking point among “working landscapes” advocates that if public lands grazing becomes unviable, home ranches will be sold and turned into subdivisions. What I have not seen is evidence where this has happened, how often it happens, or what other factors besides environmental or wildlife protections were involved if it did happen. Perhaps that evidence exists. My Google searches have not turned up anything. Maybe I’m not choosing the right search terms.

The link to the TRCP webpage you provided does not describe any specific examples of this happening, it merely alludes to it as a “real and ominous threat” without further explanation of just how pervasive this wildlife-protections-lead-to-subdivisions situation really is. It strikes me as wrong to advocate against wildlife protections on our vast public lands based on an unknown chance that some relatively small private parcel of land might possibly be subdivided as a result.

Thanks, John for your thoughtful comments.

” But the article does not describe any grazing practices that have changed to better protect habitat or prevent losses – season of use, stubble height requirements, etc. So it’s hard to gauge from this article whether ranchers or federal land managers have taken measures to address the adverse impacts grazing poses to the species.”

I’ve been trying to gather some information on this. However, there is this story about one rancher..Greg Peterson here..https://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/rancher-greg-peterson-colorado/

Working with NRCS, Peterson experimented with a sagebrush management project over 16 years ago that removed decadent, old sagebrush to reinvigorate the understory vegetation. This work is good for grouse and livestock.

“Greg has been an excellent partner in allowing us to experiment with ecological succession. With the removal of historic fire regimes, we’ve lost a lot of the diversity and hydrologic function in these systems resulting in older, more decadent sagebrush,” said With. “By setting back the successional clock, we can increase the grass and forb production. This helps not only the birds, but other wildlife species and cattle, as well.”

In addition, Peterson has implemented a rest/rotational grazing system that boosts grass and forb production. He has also experimented with grazing timing and duration, as well as installation of irrigation structures and using fencing to improve riparian areas on the ranch.

More importantly, all the private acres on his ranch have been placed in a conservation easement ensuring that key grouse – and livestock – habitat will never be lost. With his successes, these various conservation practices have branched out to other ranches across the basin.”

I’m not sure about “We recognize other threats to native species, but livestock grazing is the most pervasive human use of public lands.” I’ve seen recreationists (including hunting) everywhere (especially nowadays with GPS), but there are not cows everywhere. And they are not there year round, where clearly people are.

“As for structural injustice, it should not be a surprise that the public lands ranching industry is generally quite well-connected and politically powerful.” I’m aware of that. Where I worked in Lakeview, Oregon, ranchers were invited to Ronald Reagan’s inauguration. My point being that some people depend for their income from ranches (not all, there are the rich folks who also have them for their own reasons). In addition to owners, there are also workers and the suppliers and livestock truck drivers and so on. It is an act of privilege to say “you need to lose your job for the betterment of the world” but and while ESA is the law, the fact that “you need to lose your job but we’re not sure it will help better the world” certainly enters into thinking about the justness of it. But we can discuss that more in talking about Farrell’s book and views about ranching.

The story of sage grouse was a bit more complicated than “set aside by the Trump admin”- folks felt like they had been mistreated by the previous Admin by last-minute changes, as I documented here, and was corroborated by others involved. https://forestpolicypub.com/2019/08/07/the-sage-grouse-story-a-more-complete-view-ii-no-enemies-here-one-sources-perspective/

Yes I was simply thinking that the more difficult it is to make a go of ranching, the more folks may subdivide, not directly related to losing federal grazing permits. I’ve reached out to some folks to get more information.

Congress is the proper forum to say “you need to lose your job for the betterment of the world.” And it did that with ESA, so I read all this as arguments to amend the Endangered Species Act. I agree that someone should also be monitoring the actual costs and benefits of our laws, and considering changes where necessary, but I’m not seeing changes in the cards for ESA (beyond regulatory changes).

If the federal agencies would commit to doing what rancher Peterson did, maybe that would satisfy the plaintiffs.

But do the lawyers for the plaintiffs and for DOJ have enough expertise to make the determination of which of these changes are the best ones to try? Shouldn’t experts such as wildlife specialists (and grazing specialists) if they’re not participating in policy making? And the public, of course.

The framing of this comment doesn’t represent the lawyer-client relationship or this lawsuit accurately.

Lawyers advocate on behalf of clients and advise them about the law. Clients drive litigation and negotiation decisions. Those clients often are experts. DOJ’s clients are federal agencies that include the specialists you mention. The plaintiff conservation organizations are made up of members and employees who have extensive scientific expertise as well.

A biological opinion, like the one at issue here, must be produced using the best available science according to the ESA. Biological opinions are generally not produced with sideboards for public participation, unlike NEPA analyses. It might be nice if the public could comment on biological opinions before they are finalized, but the best available science still must drive the outcome of a biological opinion.

The comment also misunderstands what this litigation (and most public lands litigation) would do. It would not “determine which of these changes are the best ones to try.” Read the relief requested on the last page of the complaint. It asks for an injunction against grazing until proper ESA consultation is completed. If plaintiffs win, a longer term resolution would then result from following the normal process and responsibilities of the agencies.

Are there any updates to this case?

Nora Duren

College of Science and Mathematics | Biological Sciences

North Dakota State University

The litigation remains ongoing. The Gunnison County Board of Commissioners and Gunnison County Stockgrowers’ Association intervened in the case on the side of the federal defendants. The conservation plaintiffs just filed their opening brief on the merits on April 8. If you’d like me to send you that brief, let me know. The federal defendants’ and intervenors’ response briefs are due in late May. Once briefing is complete, the Court may decide to schedule an oral argument hearing. It could be many more months before the Court issues a decision on the merits of the plaintiffs’ claims.

If you could forward me the brief, that would be great. Thank you so much.

Nora Duren

College of Science and Mathematics | Biological Sciences

North Dakota State University

[email protected]