By Martin Nie, University of Montana

(This is another post that tries to make some sense of the following place-based forest bills and agreements)

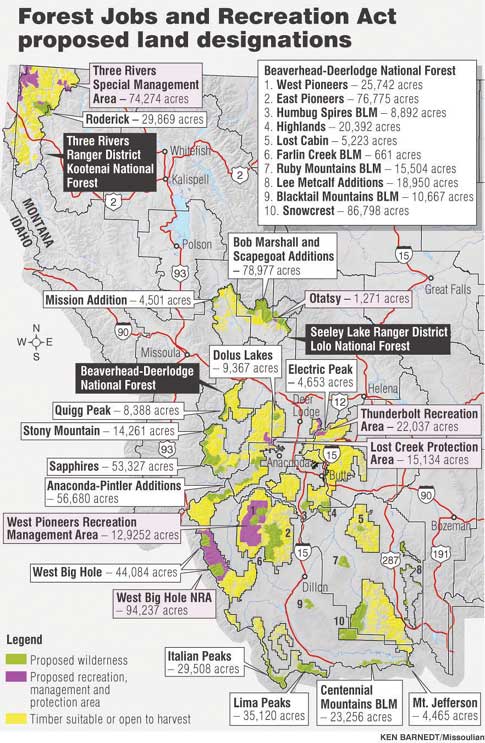

Nearly every place-based bill and initiative examined thus far focuses on the need for “landscape-scale” restoration. From a collaboration standpoint, restoration is a common zone of agreement among several of these groups. The scale is sometimes defined by reference to (sub)watersheds or acreage (e.g., 25,000 to 50,000 acres) for which restoration projects should be planned and implemented.

Though the term “landscape-scale” is now fashionable, it is often used with some imprecision. (Just how, for example, does this differ from yesterday’s focus on ecosystem management?). These cases give the term additional meaning, by occasionally making reference to other ownerships and by focusing on restoration goals that are transboundary in nature (e.g., water flow, wildlife, natural disturbances, etc.).

The place-based bills and initiatives also adopt a more ecologically-centered definition of restoration than has sometimes been used by lawmakers and the agency in the past. To be sure, all identify a clear need to mechanically treat some forests in order to reduce risks associated with uncharacteristic wildfire effects. But these initiatives go beyond this limited view and focus on additional restoration needs, such as habitat improvement, water quality, management of exotics, and road decommissioning.

Sideboards for restoration are also provided in most of these initiatives. This most often takes the form of prohibitions on new road building and road density standards. As discussed in an earlier post, these groups have also worked hard to identify areas in which restoration projects should be prioritized and areas that should be more or less left alone in some protected (roadless) status.

Many of these initiatives also adopt a landscape-level view of restoration because of economics and agency budgets. Almost all make linkages between restoration and rural economies. They operate on the principal that a viable wood products industry is necessary for the attainment and financing of various restoration goals. This explains why most of them rely so heavily upon stewardship contracting authority. Some are also premised on the economic use of restoration byproducts. Take, for example, the interest in biomass and small wood utilization: in some cases “landscape-scale” is defined by accessibility to wood products infrastructure that is at an appropriate scale to use woody biomass.

So What?

On a more general level, we should recognize that the term “restoration” is obviously open to multiple political interpretations. And that is certainly one reason why it is so popular. As a policy professor, my level of suspicion raises in proportion to the amount of agreement about something. That skepticism is warranted in cases where the agreement centers on rather ill-defined, malleable concepts like “restoration,” “forest health,” “collaboration,” “resilience,” etc. Like Congress, interest groups and the agency compromise and/or postpone future conflict by using vagueness—the ultimate political lubricant.

So what I find potentially useful about all these place-based bills and agreements is how they have negotiated the term—they have moved from the abstract and malleable to the concrete and more specific.