There’s a new paper by Morgan et al. out in Journal of Forestry in response to the Fleischman et al. paper we discussed here and here. Since I was one of the peer reviewers for this response paper, I’d like to give some of my meta-thoughts about how all this worked out- related to the biz of scientific paper publishing in general. I respect all the scientists here- we are all victims of the current system. There are some of the same solutions as in the fish disagreement I posted last Friday, even though there is no misconduct in this case.

- First, this would never have been published had some researchers not felt strongly enough about, had the time, and had access to the original data (thank you to the original authors!) to write another paper. How often does this happen? We have no clue. I’m thinking quite seldom.

- Second, much of this second paper IMHO was unnecessary and could have been resolved by the first set of reviewers simply saying “stick to the analyses you did, and don’t assert anything that isn’t a direct result of what you found.” Say, in this case, with statements about the FS budget.

- Third, an open pre-review process (even at the proposal stage) would have helped improve the first paper, and answered the questions raised in this response paper, making the original paper better, and saving us all lots of time. For example, data cleaning procedures might have been discussed, and based on that conversation, clearly documented. In any scientific field, there are only a few people who “get” the specifics of the data, how it was obtained, the lab or modelling protocols, statistics and so on. Certainly editors try to get those people for reviews, but they would be the first to say that’s not easy to do; and many heads are better than three.

- Fourth, either the Forest Service should do some sort of quality control on the PALS database, or people shouldn’t use it in research without a great many caveats. (It’s true I was involved in the development of PALS, so I do have a bias toward having it up-to-date and available to the public for our own queries.)

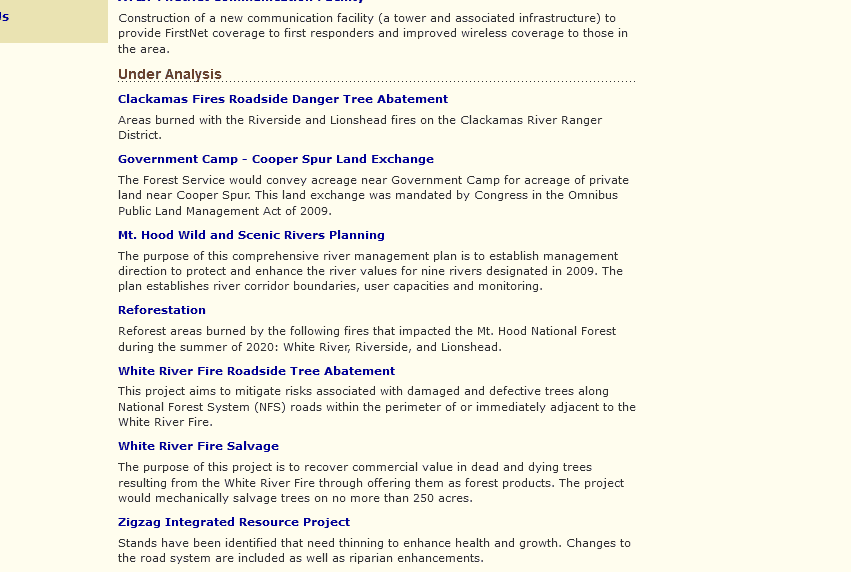

What most interested me about Morgan et al. were their observations about data in PALS and areas for improvement of PALS, as well as the need to make it easier to locate information on objections and litigation. Here’s just a brief example.

Our examination of the PALS-MYTR revealed very different elapsed days to completion for the three NEPA analysis types. Therefore, the type of NEPA analysis the agency uses for a proposed land management action should be a major determinant of the time it takes to complete that NEPA analysis. The agency was seeking, with the proposed rule changes, to increase the number of CEs it can use and to broaden some of the CE authorities. When a proposed action is suitable for a CE, its NEPA analysis is far more likely to take less time and far less likely to be litigated based on the litigation rates discussed below.

The PALS-MYTR contains 1,269 ongoing analyses, which Fleischman did not analyze. Of the ongoing analyses, 320 are identified as “complete”, 655 “in progress”, and 294 “on hold”. Many (505) of the ongoing and in progress analyses were initiated in FY 2016–2019, but there are over 400 ongoing analyses from FY 2005–2015. Presumably the on hold analyses are paused, but there were over 100 documents on hold as of April 2019 that were initiated between FY 2005 and 2013. This is a long time for a NEPA analysis to be “on hold.” This is another indication of a dataset that needs more complete documentation and checking and cleaning before it is used for policy analysis. Further, the number of elapsed days from initiation until April 1, 2019, for all ongoing analyses ranges from 101 to 5,203 days, with an average of 1,180 elapsed days (more than three years). There are more than 880 NEPA analyses ongoing and not marked complete that will have elapsed days greater than the five-month average the original authors portrayed as proof that NEPA is “fast.” By analysis type, 824 (65 %) of the ongoing analyses are CEs, followed by 331 EAs, and 114 EISs. The presence of 249 ongoing and in progress CEs and 187 ongoing and in progress EAs initiated from FY 2014–2018 does not indicate that NEPA is “fast.” These data may suggest that cleaning of the PALS-MYTR dataset should be completed before drawing conclusions about the timeliness or efficiency of NEPA.

I think it is useful to (1) have a relatively accurate database (2) have it available to the public (3) look at the database for information about managing and understanding how the FS does NEPA. Having said that, even the old GAO reports said that R-1 had more than its share of litigation. So in simple language, as I said in previous comments, you can’t just take perceived regional problems nationally and average them into not being important. I mean you can, but that’s a value, not necessarily “what the science says.”

If you want to read the whole paper (it’s a must-read for NEPA aficionados), you can ask for a e-reprint from the main author.