The Forest Service summaries are here: Litigation Weekly March 5, 2021_email

Links are provided for each case below. (There are some signs of a new administration.)

COURT DECISIONS

Apache Stronghold v. United States (D. Arizona.) – On February 12, 2021, the district court denied the Plaintiff’s motion for temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction regarding the conveyance of Oak Flat Parcel on the Tonto National Forest to developers of the Resolution Copper Mine because plaintiffs could not show immediate and irreparable injury based on their claims based on violations of the First Amendment Right to Free Exercise of Religion, Right to Petition and Remedy, Fifth Amendment Right to Due Process, and statutory rights guaranteed by the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Blogger’s update: On March 1, 2021, USDA directed the Forest Service to withdraw the Notice of Availability and rescind the FEIS and draft ROD.

Western Watersheds Project v. Bernhardt (D. Idaho) – On February 11, 2021, the district court vacated the BLM’s decision to cancel its previously proposed mineral withdrawal of 10 million acres of federal lands located in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming, which had previously been identified as Sagebrush Focal Area essential for the long-term health of sage-grouse. The court found that the BLM failed to provide a reasoned explanation for reversing its prior position that the mineral withdrawal was needed, including failing to address the fact that the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service had relied on that designation in its decision to not list the species under the Endangered Species Act. The court also held that the decision to cancel the withdrawal did not trigger NEPA requirements.

Cascade Forest Conservancy v. Hepler ((D. Or.) – On February 15, 2021, the district court issued a preliminary injunction against the Goat Mountain Hardrock Mineral Prospecting Permits on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest based on two NEPA claims, while upholding three other claims and ordering further briefing on whether an EIS is required instead of an EA. It also found no violations of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act (which was the source of funding used to purchase the parcels at issue).

Friends of the Clearwater v. Higgins (9th Cir.) – On February 23, 2021, the circuit court affirmed the District Court of Idaho’s decision denying plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction in their challenge to the Brebner Flats timber harvest and road construction project on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest regarding its effects on grizzly bears and elk.

Organized Village of Kake v. Shea (D. Alaska) – On February 25, 2021, the district court granted the government’s motion to stay the case for 120 days or until the Department of Agriculture takes action regarding the Alaska Roadless Rule, whichever occurs first. This involves the 2020 Exception that exempts the Tongass National Forest from the Roadless Area Conservation Rule, discussed previously here.

NEW CASE

Friends of the Columbia Gorge, Inc. v. USFS (D. Oregon) – On February 12, 2021, the plaintiff filed a complaint alleging that a 65-acre logging project on private forestland violates federal protections for the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

NOTICE OF INTENT

On February 22, 2021, Friends of the Clearwater sent a 60 day Notice of Intent to sue regarding the approval of the “End of the World” Project on the Nez Perce National Forest, alleging that the Forest Service violated ESA by failing to consult on the effects of the logging and road-building project on grizzly bears.

BLOGGER’S BONUS

Here’s a few other court-related activities that were going on around the same time.

Environmental Defense Fund v. EPA (D. Montana.) – On January 27, 2021, the federal district court for Montana held that the Environmental Protection Agency failed to justify its decision to make the Strengthening Transparency in Science Rule (sometimes called the “secret science rule”) take effect right after its publication in the Federal Register, instead of after 30 days, as is typical. The regulation would limit the EPA’s ability to write regulations that are unpinned by scientific research that can’t be reproduced or is based on underlying data that isn’t public. As suggested in this article, the Biden Administration has decided to reconsider the regulation.

While that regulation pertains to medical data, in a coincidence (but not an unrelated story), on the same day, the Biden Administration issued a memorandum to all federal agencies, the “Memorandum on Restoring Trust in Government Through Scientific Integrity and Evidence-Based Policymaking.” It requires federal agencies to, “conduct a thorough review of the effectiveness of agency scientific-integrity policies,” seeking to eliminate, “(i)mproper political interference in the work of Federal scientists or other scientists who support the work of the Federal Government and in the communication of scientific facts …”

(New case.) A Nevada rancher and a coalition of conservation groups have filed separate lawsuits against the BLM’s January 15th decision to allow the Thacker Pass lithium mine in northern Nevada. It could affect groundwater, sage-grouse and the federally listed Lahontan cutthroat trout, and Notices of Intent to Sue under ESA have also been filed. (The article contains links to both complaints.)

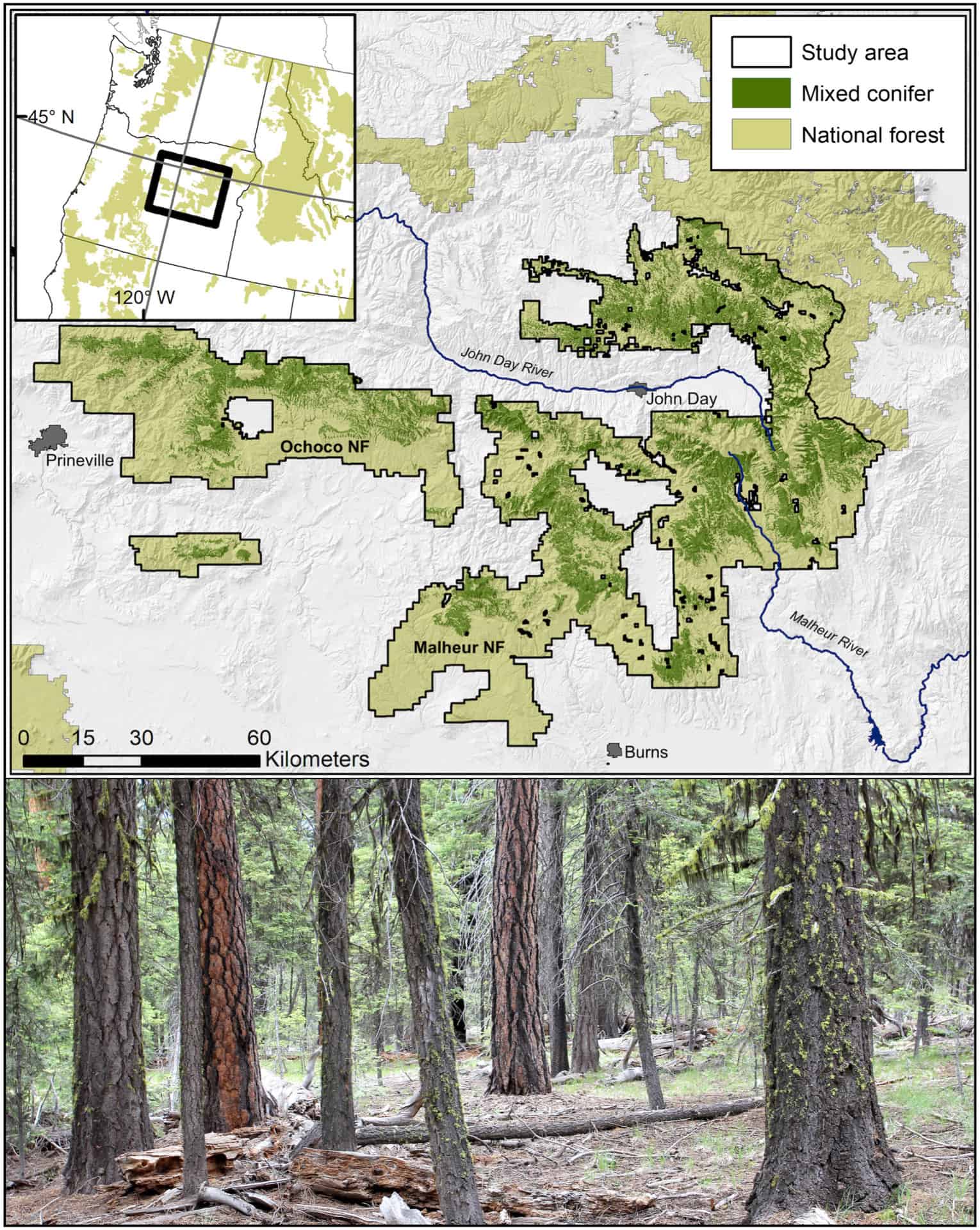

(New case.) A decision by the Ochoco National Forest to conduct a sanitation harvest of grand fir and Douglas-fir trees on 35 acres and tree thinning on 143 acres to manage root rot around Walton Lake, a popular recreation site, is being challenged again in federal district court.