Awhile back, Rene Voss commented with regard to the question “is “leaving things alone” the best for climate mitigation?”:

“There are several scientific analyses that show that leaving the forests vs. various management schemes to reduce fuels & fire risk is the best approach to help mitigate climate change.”

Mitchell et al. (2009) describes tradeoffs for managing for carbon storage (a valid goal in any forest management action) versus fuels reduction. That study suggests that, with the exception of some xeric ecosystems, “fuel reduction treatments should be forgone if forest ecosystems are to provide maximal amelioration of atmospheric CO2 over the next 100 years.” Id. at 653.

Depro et al., 2007, found that eliminating logging would result in massive increases in Carbon sequestration. “Our analysis found that a “no timber harvest” scenario eliminating harvests on public lands would result in an annual increase of 17–29 million metric tons of carbon (MMTC) per year between 2010 and 2050—as much as a 43% increase over current sequestration levels on public timberlands and would offset up to 1.5% of total U.S. GHG emissions.” (Depro et al., 2007 abstract)

Moreover, Mitchell et al. (2009) found the amount of net carbon released into the atmosphere, on an acreage basis with small diameter thinning for fuel reduction (if used for biomass), puts more carbon into the atmosphere than an average fire, on an acreage basis:

“Our simulations indicate that fuel reduction treatments in these ecosystems consistently reduced fire severity. However, reducing the fraction by which C is lost in a wildfire requires the removal of a much greater amount of C, since most of the C stored in forest biomass (stem wood, branches, coarse woody debris) remains unconsumed even by high-severity wildfires. For this reason, all of the fuel reduction treatments simulated for the west Cascades and Coast Range ecosystems as well as most of the treatments simulated for the east Cascades resulted in a reduced mean stand C storage. One suggested method of compensating for such losses in C storage is to utilize C harvested in fuel reduction treatments as biofuels. Our analysis indicates that this will not be an effective strategy in the west Cascades and Coast Range over the next 100 years.”

(my bolds)

And yet, other studies (and visible evidence) show that not burning forests is better for carbon sequestration (see the one Steve linked to here). So I went back to look at Mitchell 2009, which can be found here.

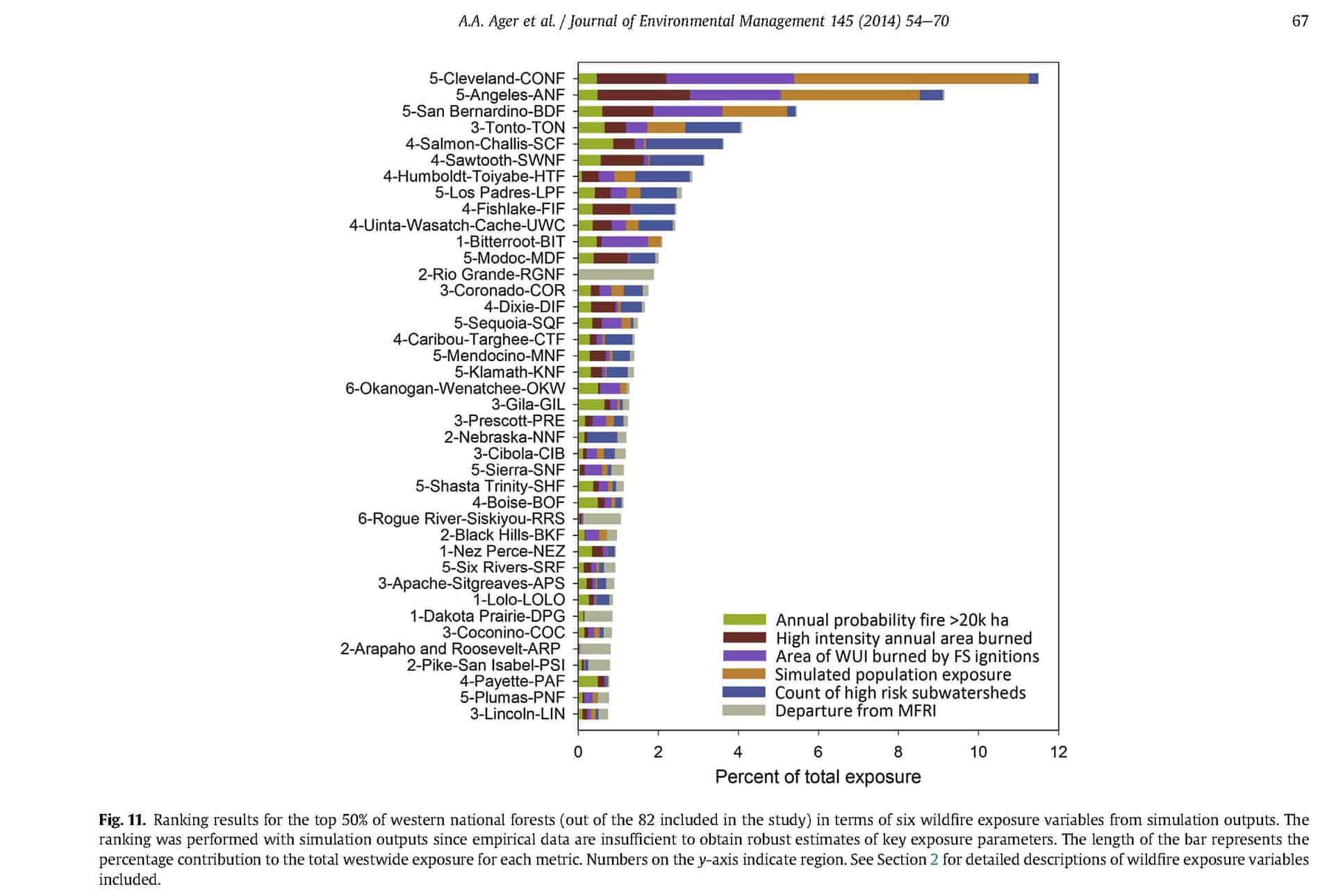

The authors picked three kinds of sites, the Coast Range, the west Cascades, and east of the Cascades (on the Deschutes). Now it may be just me, but I don’t think of fuel treatments in the Coast Range or the west Cascades. So I looked around a bit and found this interesting study by Ager et al. 2014, which indicates that no forests in the Coast Range, Western Oregon, or (surprisingly to me!) even the Deschutes are on the top 50% of areas where fires are likely to occur.

It seems likely that if an area doesn’t burn and keeps sequestering carbon that is a good carbon situation. Just like we have talked about before.. if you want to get a great deal of carbon sequestered, pick a place where trees and other plants grow well and there are no fires or bug outbreaks. On the other hand, some key questions for looking at fuel treatments are 1) is this area likely to burn and 2) are there critters or people and their stuff that need protection (despite whatever carbon impacts)? It looks like the Mitchell et al. authors selected two places unlikely to burn and said “fuel treatments will decrease carbon sequestration here.” That seems perfectly plausible. But most of us would ask “why would you even do that in the Coast Ranges and western Oregon?”. Another question is if fires are unprecedented due to cc, what do we really know about the fires of the future? Is it then “the best science” to use the past for input into models?” Or regionally downscaled climate models? Or just admit we really don’t have a clue? Or even “why do this study if the reason people do fuel treatments has very little to do with climate mitigation?”

A quick look at the Depro et al. paper that Rene also cites, shows that it is talking about timber harvests (across the country) and not fuel treatments in dry forests.

But back to Rene’s original point “several scientific analyses that show that leaving the forests vs. various management schemes to reduce fuels & fire risk is the best approach to help mitigate climate change.” To my mind that’s not what actually these studies show, and not exactly what the authors said in the papers.