Jon posted this quote from one person’s opinion about the George Washington National Forest and 30 x30. But I have seen this same concept stated in other places that I can’t locate right now.

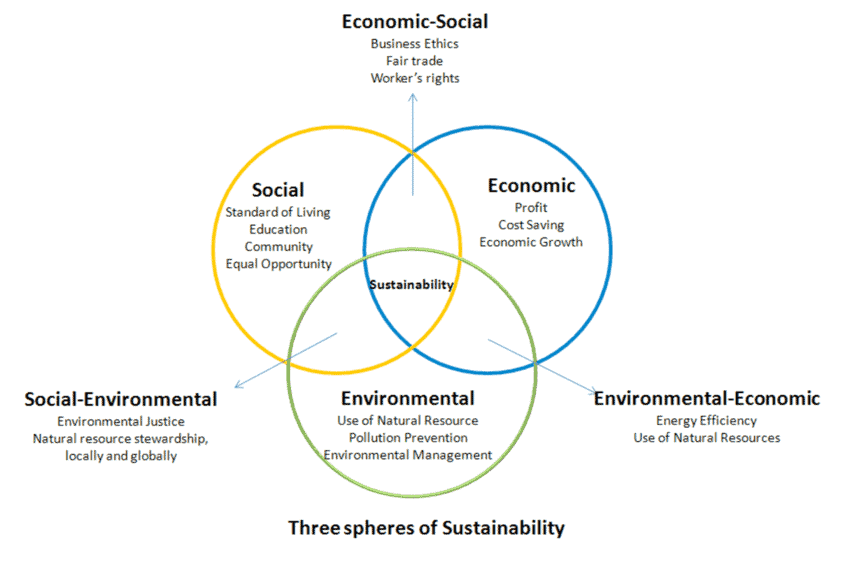

By protection, I mean minimizing human activity in order to allow for “as natural a state as possible”. This approach is termed proforestation, letting standing forests grow and develop in complexity to their natural old growth state; such restoration is also the most effective way to counter climate change.

I think it’s what was behind many of the 20th century federal lands debates (the LTA concept-leaving things alone, except for preferred forms of recreation, is best for the environment). Still, given the narrative that Anthropogenic Global Warming is the primary environmental problem of the day (crisis), reasonable people have to wonder whether this “LTA is best” remains a true statement. You’ll notice that in the Biden Admin press release on 30×30, it mentions the extinction crisis but doesn’t state that “protecting” areas (to be defined by DOI?) will help with climate change.

So it will be interesting to see how this plays out in various news stories, op-eds and so on. But we can think of various situations in which LTA does not seem to be the best for action on reducing GHGs.

1. Build-out of infrastructure for solar and wind, with accompanying transmission; also pipelines for carbon capture.

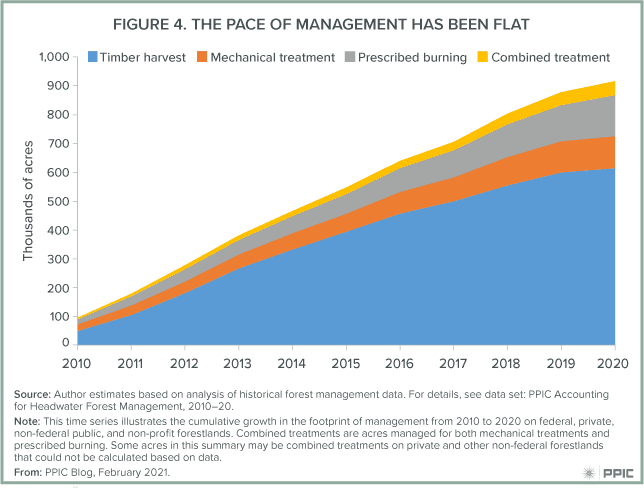

2. Leaving fires alone can lead to deforestation and less carbon being soaked up, see Hayman Fire for example. It’s possible that planting is OK in “protected” areas, but if you’re going for Wilderness, believe it or not, I recall at one time folks said you couldn’t plant disease-resistant whitebark pine in Wilderness because it was unnatural. Maybe it’s the breeding (so they survive) and not the planting that makes it unnatural? Would fuel treatments be OK in these protected areas, or just prescribed burning, or ?? Or maybe suppression shouldn’t occur either. So many questions and complexities, that are not ultimately not scientific in nature.- because protection is an abstraction, and abstractions are usually defined by … those with privilege.

3. No drilling or mining of fossil fuels will likely lead to increased development on private lands and/or more imports (that’s what decreasing supply without changing demand has historically done. Thank you economists!). Now, logically, transporting imports from another country may lead to more use of fossil fuels in the act of transporting.

Can you think of other situations in which “leaving things alone except for currently preferred forms of recreation” is not best for climate?

Sidepoint: it is conceivable that any recreation form that requires gas-powered or electricity sourced from fossil fuel energy (a high proportion of most electric grids nowadays), is also not good for the climate. However, I don’t see anyone proposing a regulation that all skiers at FS permitted ski areas arrive only by certified carbon-free vehicles.

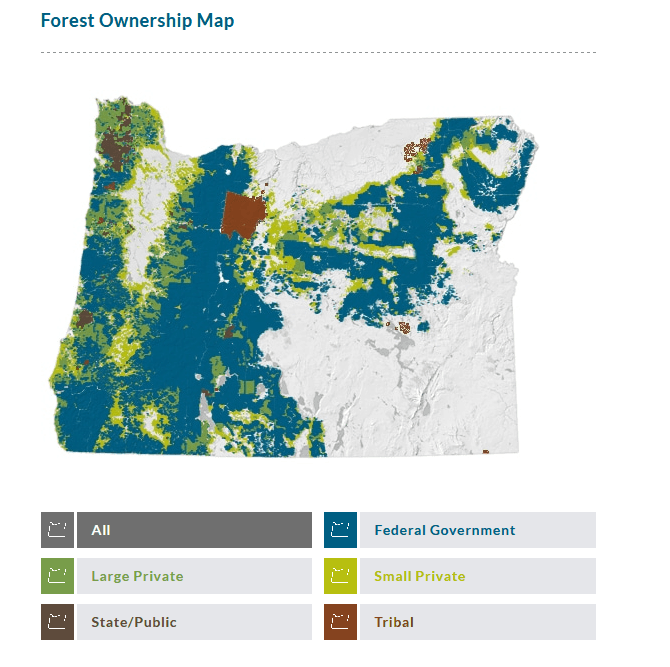

My other point about 30×30 is that if we can’t meet our own energy and minerals needs from our own land because we are “protecting” it.. are we merely exporting the impacts on biodiversity to somewhere else, whose biodiversity is just as desirable (or possibly more, for whatever reasons that specialists in the various kinds of biodiversity can think up) as our own?

And of course, there are arguments that for social justice toward our own working classes that we would not want to export jobs. Then there’s the same old forest products argument that asks if the other country’s labor and environmental protections are as good as ours? But we still import wood from Canada, a friendly and benign ally with similar rules. To say it gently, our relations with countries such as China, Russia, the Saudis and so on are more geopolitically complex. Not to speak of the concept of balance of trade being a thing worthy of consideration somewhere in all this.

The logical thing to do IMHO seem to be to start with the new infrastructure, and then see what’s left to put into protection. Otherwise, it seems a bit disorganized – especially for solutions to the #1 problem and crisis in the world, that we need to act on urgently. On the other hand, various scientists and folks like the TNC say that some places are more worth protecting that others. Hopefully, all these concerns will line up- but right now there doesn’t appear to be a mechanism to do that. Or maybe the Biden Admin will be more welcoming of nuclear because more land could be “protected?” Will be interesting to watch.

Another thought, if the US becomes a “park” country, at the expense of other countries becoming “industrial zone” countries, is that a good thing? For whom? What is the net impact on the environment?

Anyway, it seems to me that some people see 30 x 30 as just another opportunity to restate “LTA is best,” with “besides, it’s the best thing for climate” perhaps, as a rhetorical flourish more than a statement of reality.