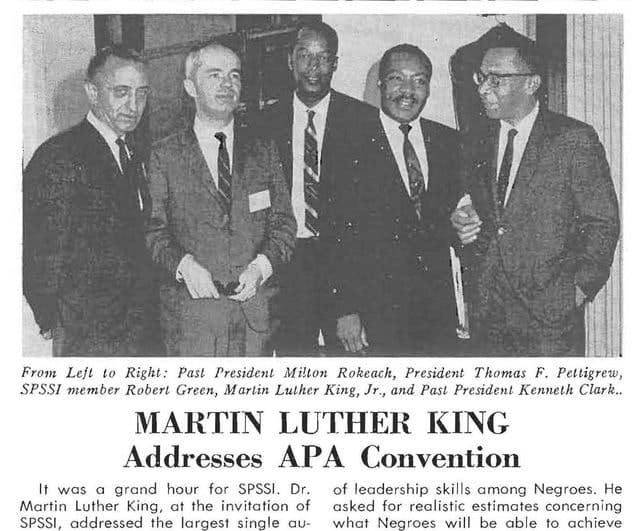

Dr. King observed, astutely, that the social sciences often deal in uncomfortable knowledge: “These are often difficult things to say but I have come to see more and more that it is necessary to utter the truth in order to deal with the great problems that we face in our society.”

In a clear understatement, he noted that there were many opportunities for social science research “to assist the civil rights movement.” Three examples he cited were research on leadership in the Black community, the effectiveness of political action of the civil rights movement, and psychological and ideological changes within the Black community as societal change occurs.

Ultimately, Dr. King asked social scientists to help gauge progress, including assessments of direction and pace: “Are we moving away, not from integration, but from the society which made it a problem in the first place? How deep and at what rate of speed is this process occurring? These are some vital questions to be answered if we are to have a clear sense of our direction.”

Roger adds “Such questions are fundamental to all policy research.”

If we thought that justice for disadvantaged communities is one of the most important needs of our country, what would that budget and research priorities look like? What would it take to make sure that research is co-designed and co-produced with representatives of those communities?”

It’s not that hard to imagine. When I worked on the Fund for Rural America, we gave a research grant to a rural community group to do exactly that. This was highly unpopular with the Science Establishment and the universities. Can we imagine, say 100 million to start, each for representatives of Black, Native American, Latino/Hispanic and Asian-Americans to co-design and co-produce social science research? I’d think we could afford it, simply by establishing coordinating groups for policy-relevant research that would ride herd on duplication across agencies and downright “not all that useful for policy but claim to be” proposals.

Fifty years ago, perhaps we thought “if we just hired more diverse people, the research would naturally change to their interests.” Well, it seems to have been harder than we had thought to hire more diverse people, and federal research priorities and budget have their own momentum and vested interests.

While the social sciences have diversified significantly since the 1960s in terms of both scholars and scholarship, the various disciplines that comprise the social sciences still have a long way still to go. For instance, top university social science departments continue to be overwhelmingly populated by white males, and Black and Latino students continue to be under-represented on our leading campuses.

And while we can look at the Forest Service and see that females are heavily represented among researchers and practicing social scientists, this study from 2019 says:

Most faculty are male, although there appear to be critical masses of women in political science and sociology. Blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented among faculty relative to their shares of the population. Within each racial-ethnic group examined, there are more male than female faculty members, with a smaller gender gap for Blacks than for other racial-ethnic groups. In general, the higher the rank, the greater the proportion of males than females, especially for Whites and Asians.

According to this January 16 AP Story, President Biden announced his appointment of a Science Advisor and others.

The president-elect noted the team’s diversity and repeated his promise that his administration’s science policy and investments would target historically disadvantaged and underserved communities.

I hope President-Elect Biden means “co-create” a new body of scientific information with underserved communities as full partners in funding, design, and production, with open peer review and open access to research results.