…biomass plants nationwide [have] together have received at least $700 million in federal and state green-energy subsidies since 2009, a calculation by The Wall Street Journal shows.Yet of 107 U.S. biomass plants that the Journal could confirm were operating at the start of this year, the Journal analysis shows that 85 have been cited by state or federal regulators for violating air-pollution or water-pollution standards at some time during the past five years, including minor infractions.

Colt Summit Lynx Cumulative Effects: Let’s Hear Both Sides

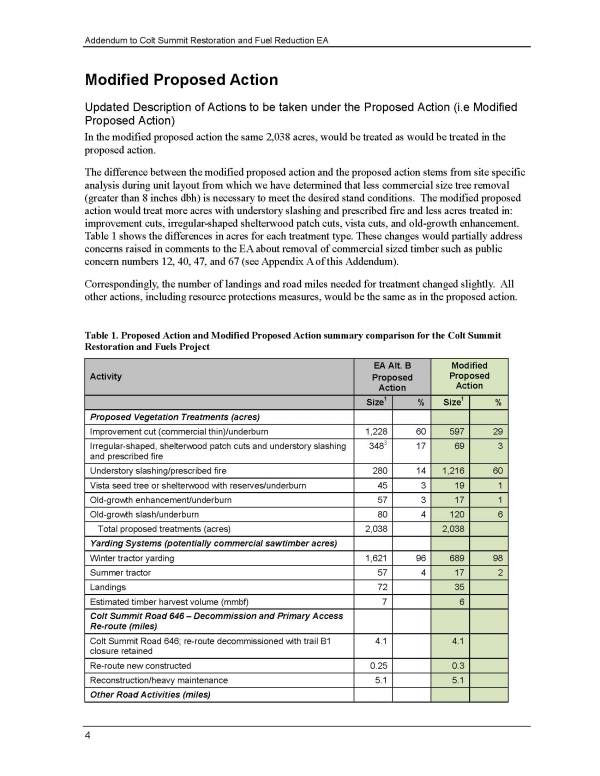

I think it would be interesting to investigate further exactly what the FS did right with the cumulative effects of other species, and apparently, according to Judge Molloy, did wrong with lynx.

It seems odd to me that the FS would do an adequate analysis for the other species, but not for lynx (look at past, present and reasonably foreseeable future actions). Below is a quote from Judge Molloy’s decision (italics in both below quotes are mine) :

Once an agency detemines the geographical scope of its cumulative-effects

analysis, it must analyze the incremental impact of the proposed project when

added to past, present, and reasonably foreseeable actions within the selected

geographical area. Ctr for Envtl. Law & Policy, 655 F.3d at 1007; 40 C.F.R. §

1508.7. The plaintiffs in this case insist the Forest Service’s cumulative effects

Cumulative effects on lynx analysis for lynx is inadequate. On this point they are correct. On remand the

Forest Service must prepare a supplemental EA that adequately addresses the

cumulative effects for lynx, and if necessary after that review, an EIS.

“Consideration of cumulative impacts requires some quantified or detailed

information that results in a useful analysis, even when the agency is preparing an

EA and not an BIS.” Id. “An EA’s analysis of cumulative impacts ‘must give a

sufficiently detailed catalogue of past, present, and future projects, and provide

adequate analysis about how these projects, and differences between the projects,

are thought to have impacted the environment.'” Te-Moak Tribe ofW. Shoshone of

Nev. v. U.S. Dept. ofInt., 608 F.3d 592, 603 (9th Cir. 2010) (quoting Lands

Council v. Powell, 395 F.3d 1019, 1028 (9th Cir. 2004)). “An agency may,

however, characterize the cumulative effects ofpast actions in the aggregate

without enumerating every past project that has affected an area.” Ctr for Envtl.

Law & Policy, 655 F.3d at 1007.

When there is no BIS containing a cumulative effects analysis, “[T]he scope

of the required analysis in the EA is correspondingly increased.” Kern, 284 F.3d at

1077. “Without such information, neither the court nor the public … can be

assured that the [agency] provided the hard look that it is required to provide.” Te

Moak Tribe ofW Shoshone ofNev. , 608 F.3d at 603 (citations and internal

Depending on what the cumulative effects analysis

shows, the Forest Service might be required to prepare an EIS for the Project. See

40 C.F.R. § 1508.27(b)(7).

Here, the Forest Service did not discuss or mention any past projects oractions in its cumulative effects analysis for lynx. (See EA, A-I FS000066.) In the

EA, the Forest Service discusses how it recently acquired 640 acres ofland owned

by Plum Creek Timber Company. (fd.) It discusses the impact of snowmobile

activity in the area. (Id.) But there is no discussion of past projects or activities.

Even assuming there are no past projects or activities that would have a

cumulative effect when considered along with the Colt Summit Project, the Forest

Service must still “characterize the cumulative effects of past actions in the

aggregate.”

“neither the court nor the public … can be assured that the [agency] provided the

hard look that it is required to provide.” Te-Moak Tribe ofW. Shoshone ofNev. ,

608 F.3d at 603 (citations and internal quotation marks omitted).

etr for Envtl. Law & Policy, 655 F.3d at 1007.

I thought it would be interesting to compare the Judge’s statements to the US Attorneys’ on the point of cumulative effects on lynx, but don’t have a PACER account, nor would I know exactly what document to look for. To me, it would be illuminating to hear both sides. Can someone help locate this document, so we can hear the other side?

I could easily find the appeal response here (worth looking at to examine the kitchen-sinkery that the plaintiffs started with during the appeal).

Issue 32. The appellants allege the significance of the cumulative effects of habitat

fragmentation and reduction due to logging, road building, fire suppression, and other

management activities in regards to their effects on population levels or viability was not

disclosed.

Response: The Wildlife Report (PF, Doc. A-20, Table 5, pp. 14 to 15) indicates the project may

impact some individuals of some species, but there is no indication of project effects on

population levels or species viability of any threatened, sensitive, or management indicator

species.

Fragmentation is discussed in the Wildlife Report (PF, Doc. A-20, pp. 93 to 96). It concludes

that the proposed action would have “no impact” on fragmentation, corridors, or linkages

because the vegetation would not be altered beyond patterns that occur naturally from fire and

other disturbance, and open road density would not increase.

Cumulative effects discussions are covered in the Wildlife Report’s affected environment

sections (PF, Doc. A-20). Effects for connectivity, fragmentation, and linkages are discussed

where that issue has been raised: lynx (pp. 27 to 31); grizzly bear (pp. 35 to 45), fisher (pp. 49 to

52), wolverine (pp. 53 to 54), northern bog lemming (pp. 55 to 56), Townsend’s big-eared bat

(pp. 57 to 58), black-backed woodpecker (pp. 60 to 65), flammulated owl (pp. 67 to 70), boreal

(western) toad (pp. 70 to 72), northern goshawk (pp. 76 to 81), elk (pp. 81 to 85), and pileated

woodpecker (pp. 87 to 91).

The Biological Assessment for lynx and grizzly bear (PF, Doc. A-25) and subsequent letters of

concurrence (PF, Doc. K-14) indicate the USFWS concurred with the determinations for these

species (which include analyses on linkage and corridors). The record discusses effects of

habitat fragmentation on population levels and viability and is in compliance with NEPA,

NFMA, and ESA.

Historical Vegetation Ecologists Duke it Out: Does It Matter?

I saw this study a couple of days ago but didn’t have time to do it justice. However a thoughtful reader suggested it so here goes..

Here’s a link to the AP story. Below are some excerpts:

Researchers at the University of Wyoming studied historical fire patterns across millions of acres of dry Western forests. Their findings challenge the current operating protocol of the U.S. Forest Service and other agencies that today’s fires are burning hotter and more frequently than in the past.

Combing through 13,000 firsthand descriptions of forests and retracing steps covering more than 250 miles in three states, where teams of government land surveyors first set out in the mid-1800s to map the nation’s wild lands, the researchers said they found evidence forests then were much denser than previously believed.

“More highly intense fire is not occurring now than historically in dry forests,” said William Baker, who teaches fire ecology and landscape ecology in Laramie, Wyo., where he’s been doing research more than 20 years. “These forests were much more diverse and experienced a much wider mixture of fire than we thought in the past, including substantial amounts of high-severity fire.”

If he’s right, he and others say it means fuel-reduction programs aimed at removing trees and shrubs in the name of easing fire threats are creating artificial conditions that likely make dry forests less resilient.

“It means we need to rethink our management of Western dry forests,” said Baker, a member of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service working group that is developing plans to help bolster northern spotted owl populations in dry forests.

Baker’s conclusions have drawn sharp criticism from other longtime researchers who believe that decades of fire suppression have led to more densely tangled forests and more intense fires, the position advanced by the Forest Service.

“I have yet to hear any knowledgeable forest or fire ecologist or forest manager say they are convinced by the main interpretations in that (Wyoming) paper,” said Thomas Swetnam, a professor of dendrochronology and director of the Laboratory of Tree Ring Research at the University of Arizona. “I doubt it will gain much traction in the scientific or management communities.”

And..

Williams said the Wyoming studies have significant implications for wildlife that depends on post-fire habitat, such as the black-backed woodpecker, which has survived for millions of years by eating beetle larvae in burned trees.

Four conservation groups filed a petition with the U.S. Interior Department in May seeking Endangered Species Act protection for the bird in the Sierra Nevada, Oregon’s Eastern Cascades and the Black Hills of eastern Wyoming and western South Dakota.

The new studies provide the first “real, direct data'” showing that more forests burned historically, creating more post-fire forest habitat, said Chad Hanson, a forest ecologist and director of the John Muir Project who is helping lead the listing effort and suing the Forest Service to block post-fire logging in woodpecker habitat near Lake Tahoe.

“It indicates the woodpeckers had more habitat historically than they do now,'” Hanson said.

Note from Sharon: A couple of points

1. OK, so I have worked in central Oregon, the Sierra, and Colorado and Wyoming. I don’t think I would use data from one to make judgments about the other. In fact, the Blue Mountains were very different from the east side of the Cascades. Yes they all have “ponderosa pine” but to me that says more about the wondrousness and adaptability of PPine than it says about any similarity of environment. Just look at their co-trees in the overstory and the understory.

2. If climate change means more and larger fires (can’t remember if the researchers who said this also said said “more intense”) what relevance does the historical data possess? Are the authors saying that we should manage to keep fires smaller than we might expect given the climate change future, or should we manage for more acres than the fire suppression past? What is the goal for the amount of post-fire habitat (same as what, 900 AD? 1560?). Or perhaps more habitat than the past for the woodpecker is OK to woodpecker watchers, but what if that’s less habitat for everything else?

3. My favorite leap in this article is :

If he’s right, he and others say it means fuel-reduction programs aimed at removing trees and shrubs in the name of easing fire threats are creating artificial conditions that likely make dry forests less resilient.

“It means we need to rethink our management of Western dry forests,” said Baker, a member of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service working group that is developing plans to help bolster northern spotted owl populations in dry forests.

Unless you assume that historical data are “what we should manage for” why would thinning make a forest “less resilient”? Is there a proposed specific mechanism for that “less resilience”? We know that trees grow more slowly and lose vigor when they are dense and droughts occur. Are they saying that if fuel treatments are deemed to be “unnatural” then we shouldn’t do them? It’s all very confusing.

Then there’s

Now, he believes thinning and post-fire salvage operations should be re-examined and emphasis placed on maintaining high-density stands in certain circumstances that would not threaten people or homes.

“We shouldn’t be managing just for low-density forests,” he said. “We should not be unhappy with — or perhaps even manage for — higher severity fires in the forests.”

Are these folks aware that most stands are (and have to be, it costs money to manage) things left alone? This goes back to Derek’s percentage of acres in treatment question.. if we are treating <5%, isn't 95% managed that way enough? Further, it is an odd world where there is plenty of bucks to go back and examine conditions two hundred years ago, but there doesn't seem to be any to answer Derek's question.

Just because high severity fires occurred in the past, doesn't seem to me that we would necessarily "manage for them" in the future, as they can have negative impacts to soils.

I guess I’m with Wally on this one..

Wallace Covington, the director of the Ecological Restoration Institute at Northern Arizona University, takes no issue with the Wyoming duo’s data collection or statistical analysis but said some of Baker’s conclusions don’t follow from his data. Covington first testified before Congress in 2002 about the urgent need to thin forests to guard against catastrophic wildfires and insists it’s still necessary.

House Bill Standardizing Fees for Recreation Residences

Here’s the link, below is an excerpt..

The House Natural Resources Committee last week reported the Cabin Fee Act of 2011 (H.R. 3397), which would standardize the fee structure. The committee approved the bill last November but waited till now to officially send it to the House floor for a vote.

Owners would only have to pay $100 a year “if access to a cabin is significantly impaired, either by natural causes or governmental actions, such that the cabin is rendered unsafe or unable to be occupied,” according to the committee report on the bill.

And when someone sells a cabin or transfers title, the government would collect a transfer fee.

The U.S. Forest Service has always collected fees from cabin owners but in a haphazard manner that did not accurately reflect their valuation – sometimes more than $10,000. And many owners couldn’t afford them.

The bill would set a structure of fees ranging from $500 to $4,500 per year.

The transfer fee would consist of $1,000 for all sales and transfers plus an additional five percent on prices between $250,000 and $500,000, and an additional 10 percent on sale amounts exceeding $500,000.

Companion legislation (S. 1906) is pending before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Subcommittee on Public Lands and Forests, which conducted a hearing in March. Here is a link to the bill.

Note from Sharon: I wonder about the causes of what the reporter (or the Congressfolk) terms “haphazard” .. there is a great deal of political pressure not to increase the fees by recreation residencers, but the FS is attempting to implement regulations, which are conceivably based on the intent of Congress and probably have some kind of deadline to collect the currently appropriate fees. I wonder if there is more to this story, and about the perspectives of people who contribute to this blog on recreation residences and fees?

Stewardship Contracting Authority – What Do You Think?

One of my colleagues (not FS) asked the question “what are the pros and cons of stewardship contracting in your opinion?” My story has been it’s a good idea but you need trees to have positive economic value, so we have problems with that in large parts of the interior West.

We are interested in your stories… seems like members of our community share a variety of (thankfully, non-partisan!) perspectives and have on-the-ground experience. What’s been your experience? Are there things you would like to change about the program?

Thanks in advance for your ideas.

The Impact of Catastrophic Forest Fires and Litigation on People and Endangered Species: Time for Rational Management of our Nation’s Forests

Thanks to Bob Berwyn for finding this in time for some of us to watch..here’s the link to the site.. they may post the video later.

Observing this, I think we need to move beyond partisan blathering, snarkiness and grandstanding to do good public policy. I’m simply embarrassed by our elected leadership on both sides. There really is middle and common ground- but the 4FRI people spent the time to figure it out. It looks like all national pols want to do is use the latest public problem to bash the “other side,” in my opinion simply defaulting on their true responsibilities as elected officials.

PS I can’t believe they asked Joe Romm to talk about climate bark beetles, forest and wildfire. If you follow the climate debates, you might want to check on some of what he says and of course, how careful he is about what he says. Here’s a link to one debate. We have people who actually spend their lives studying these things..I don’t agree always agree with their perspectives (and they disagree with each other), but at least they are studying our situation here.

What we should agree to do about the situation we’re in is a different question than what caused it..we may never know the percentage of the situation caused by fire suppression, non climate change droughts, and climate change. Markey seems to be arguing that westerners should not be concerned about what’s happening in their backyards, and how that is influenced by federal land policy, because other people have problems also..???

Joe Romm and applied silviculture assessments in HFRA in the same hearing… Gaia must be smiling somewhere at our antics!

Mary Wagner is a class act, IMHO.

Just wanted to point out that Massachusetts got $41.5 million in 2010 to deal with Asian Longhorned Beetle, which I believe was more than the new money all of Region 2 (Wyoming, Colorado, S. Dakota, Nebraska) received to deal with bark beetle. Here’s the link. But perhaps ALB is not affected by climate change, so that’s OK.

Even More Praise of the Dead

When I read Wuerthner’s contribution I was struck by how it could be perceived as “kingdomist”, that is animal “kingdom”-o-centric. Actually “kingdom” is sexist so we should probably pick another word. So I rewrote it from a less “queendomist” perspective… with apologies in advance to anyone who is offended ;)..

Dead. Death. These are words that we don’t often use to describe anything positive. We hear phases like the walking dead. Death warmed over. Nothing is certain but death and taxes. The Grateful Dead. These are words that do not engender smiles, except among Grateful Dead fans. We bring these pejorative perspectives to our thinking about forests. In particular, some tend to view dead animals as a missed opportunity for a meal. But this really represents an economic value, not a biological value.

From an ecological perspective dead animals are the biological capital critical to the long-term health of the forest ecosystem. It may seem counter-intuitive, but in many ways the health of a forest is measured more by its dead animals than live ones. Dead animals are a necessary component of present forests and an investment in the future forest.

I once visited a District Ranger who went on and on about his plans for an fall elk-hunting trip. Maybe he didn’t realize the importance of dead elk remaining exactly where they should be so that the ecosystem can flourish, instead of the vital nutrients being wasted in a municipal sewage system. Or perhaps a septic tank, depending on where he lives.

I had a good lesson in the value of dead animals a few summers ago when I was taking a class in carnivores. We learned how many different species feed on elk and bison carcasses, from grizzlies and wolves to crows to various invertebrates. And of course, bones and other pieces of animals leach into the soil, nurturing plants.

Dead animals are a biological legacy passed on to the next generation of forest dwellers including future generations of wildflowers and trees..

Dead animals have many other important roles to play in the forest ecosystem. They provide homes for invertebrates.

Dead animals are the biological capital for the forest. Just as floods rejuvenate the river floodplain’s plant communities with periodic deposits of sediment, episodic events like major freezing, starvation or disease events are the only way a forest can recruit the massive amounts of dead animals required for a healthy forest ecosystem. Such infrequent, but periodic events may provide the bulk of a forest’s input of nutrients for a hundred years or more.

All of the above benefits of dead animals are reduced or eliminated by our common forest management practices. Hunting removes these all important nutrients to where they are unavailable to plants. Creation and recruitment of dead animals is not a loss, rather it is an investment in future forests.

If you love birds, you have to love dead animals. If you love fishing, you have to love dead animals. If you want grizzlies to persist for another hundred years, you have to love dead animals.So when you get a whiff of a particularly ripe carcass, try to view these events in a different light-praise the dead: the forest will be pleased by your change of heart.

Will Peace Break Out in the US/Canada Softwood “Wars”?

I like peace and deals, in general, as opposed to litigation…I like the optimism of this article from the Vancouver Sun. Thanks to Craig Rawlings, Forest Business Network, for this! Note the quote below: “we’re learning to work together rather than fight over litigation.”

Here’s an excerpt:

Although there’s little doubt U.S. agitators will continue to pursue these kinds of actions, the threat to U.S. producers from Canadian lumber exports is not what it was. The recession and U.S. housing crisis altered the dynamics of the market, as both lumber production and prices fell. Canada’s share of the U.S. market dropped to barely 25 per cent — exports of softwood lumber fell from $9.6 billion in 2004 to $2.6 billion in 2009. Many analysts now expect Canada’s average market share will not return to previous levels but rather hover around 27 per cent for years to come.

As Canada’s exports of softwood lumber to the U.S. declined, so too did Canada’s dependence on the U.S. market. In 2004, 81.1 per cent of Canada’s lumber exports were destined for the U.S; by 2010, the proportion was 58.7 per cent.

What happened is that Canada — and, for the most part, we’re talking about British Columbia, which accounts for nearly 60 per cent of Canada’s lumber exports — found a voracious new market in China.

Since 2003, B.C.’s softwood lumber exports to China have risen by 1,500 per cent; and the value of exports was up 60 per cent in 2011 alone, surpassing the $1-billion mark for the first time. Lumber sales to China have grown from $900 million in 2006 to $3.2 billion in 2011, representing growth in the share of exports from 6.6 per cent to 28.8 per cent.

John Allan, president of the B.C. Lumber Trade Council, explained that China is drawn by the attributes of wood — namely seismic performance, carbon sequestration and energy efficiency, adding that B.C. producers are unlikely to abandon the Chinese market no matter what happens south of the border.

“We learned a lesson in diversifying our markets to China and ignore that lesson at our peril,” he said. “We’ll need to keep an eye on the U.S. recovery and housing starts and that will dictate where negotiations go toward a new agreement.”

Another sea-change that will affect future negotiations is the warming relationship between Canadian and U.S. producers. They have found common cause in the promotion of wood and have joined forces to market it globally. The so-called checkoff system, developed over the last three years by the Binational Softwood Council (established by the Canadian and U.S. governments under the Softwood Lumber Agreement) and overseen by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, imposes a charge on all lumber producers to fund a marketing scheme to promote the use of wood. “We’re learning how to work together versus fighting over litigation,” Allan said.

The reduced threat from exports, more diversified markets and a new spirit of cooperation will change the tenor of negotiations and their outcome.

It may even come to pass that no treaty with restrictions, quotas, tariffs and taxes will be necessary. Perhaps the risks and rewards of free trade will finally be extended to lumber, not only giving Canada access to the U.S. market but spreading the benefits of building with wood to the rest of the world.

Praise the Dead: The Ecological Value of Dead Trees

The following is a guest post from George Wuerthner.

Dead. Death. These are words that we don’t often use to describe anything positive. We hear phases like the walking dead. Death warmed over. Nothing is certain but death and taxes. The Grateful Dead. These are words that do not engender smiles, except among Grateful Dead fans. We bring these pejorative perspectives to our thinking about forests. In particular, some tend to view dead trees as a missed opportunity to make lumber. But this really represents an economic value, not a biological value.

From an ecological perspective dead trees are the biological capital critical to the long-term health of the forest ecosystem. It may seem counter-intuitive, but in many ways the health of a forest is measured more by its dead trees than live ones. Dead trees are a necessary component of present forests and an investment in the future forest.

I had a good lesson in the value of dead trees last summer while hiking in Yellowstone. I was walking along a trail that passes through a forest dominated by even-aged lodgepole pine. Judging by the size of the trees, I would estimate the forest stand had its start in a stand-replacement blaze, perhaps 60-70 years before. Strewn along the forest floor were numerous large logs that had fallen since the last fire. Fallen logs are an important home for forest-dwelling ants. Pull apart any of those old pulpy rotted logs and you would find them loaded with ants. Nearly every log I pass along the trail had been clawed apart by a grizzly feasting on ants. It may be difficult to believe that something as small as ants could feed an animal as large as a grizzly. Yet one study in British Columbia found that ants were a major part of the grizzly’s diet in summer, especially in years when berry crop fails.

Who could have foreseen immediately after the forest had burned 60 years before that the dead trees created by the wildfire would someday be feeding grizzly bears? But dead trees are a biological legacy passed on to the next generation of forest dwellers including future generations of ants and grizzly bears.

Dead trees have many other important roles to play in the forest ecosystem. It is obvious to many people that woodpeckers depend on dead trees for food and shelter. In fact, black-backed woodpeckers absolutely require forests that have burned. Yet woodpeckers are just the tip of the iceberg so to speak. In total 45% of all bird species depend on dead trees for some important part of their life cycle. Whether it’s the wood duck that nests in a tree cavity; the eagle that constructs a nest in a broken top snag; or the nuthatch that forages for insects on the bark, dead trees and birds go together like peanut butter and jelly. Birds aren’t the only animals that depend on dead trees. Many bats roost in the flaky bark of old dead snags and/or in cavities.

When a dead tree falls to the ground, the trunk is important habitat for many mammal species. For instance, one study in Wyoming found that without big dead trees, you don’t have marten. Why? Marten are thin animals and as a consequence lose a lot of heat to the environment, especially when it’s cold. They can’t survive extended periods with temperatures below freezing without some shelter. In frigid weather, marten dig out burrows in the pulpy interiors of large fallen trees to provide thermal protection. They may only need such trees once a winter, but if there are no dead fallen trees in its territory, there may not be any marten.

Many amphibians depend on dead trees. Several studies have documented the close association between abundance of dead fallen logs and salamanders. Eliminate dead trees by logging and you eliminate salamanders. Even fish depend on dead trees. As any fisherman can tell you, a log sticking out into the water is a sure place to find a trout lying in wait to grab insects. If you talk to fish biologists they will tell you there is no amount of fallen woody debris or logs in a stream that is too much. The more logs, the more fish.

Even lichens and fungi are dependent on dead trees. Some 40% of all lichen species in the Pacific Northwest are dependent on dead trees and many are dead tree obligates, meaning they don’t grow anyplace else.

Dead trees fill other physical roles as well. As long as they are standing, they create “snow fences” that slows wind-driven snow. The snow that is trapped, melts in place, and helps to saturate the ground providing additional moisture to regrowing trees. Dead trees that fall into streams stabilize and armor the bank, slowing water, and reducing erosion. Dead trees create hiding cover and thermal cover for big game as well.

I was once on a tour with a Forest Service District Ranger who wanted to conduct a post fire logging operation. We were standing near the open barren landscape of a recent clearcut that was adjacent to the newly burnt forest. I pointed out to him that the black snags still had value. He couldn’t see anything but snags waiting to be turned into lumber. I said the snags were still valuable for big game hiding cover. He dismissed my idea out of hand. So I challenged him. I said I have a rifle and you have two minutes to get away from me. Where are you going to run? He didn’t have to ponder the point very long.

Even more counter-intuitive is that dead trees may reduce fire hazard. Once the small twigs and needles fall off in winter storms their flammability is greatly reduced. By contrast, green trees, due to the flammable resins contained in their needles and bark, are actually more likely to burn than snags under conditions of extreme drought, high winds and low humidity. Under such extreme fire-weather conditions, I have seen trees like subalpine fir explode into flame as if they contained gasoline. Fine fuels are what drive fires, not large tree trunks. Anyone who has fiddled around trying to get campfire going knows you gather small twigs, and fine fuels. You don’t try light a twenty inch log on fire.

Dead trees are the biological capital for the forest. Just as floods rejuvenate the river floodplain’s plant communities with periodic deposits of sediment, episodic events like major beetle kill and wildfire are the only way a forest can recruit the massive amounts of dead wood required for a healthy forest ecosystem. Such infrequent, but periodic events may provide the bulk of a forest’s dead wood for a hundred years or more.

All of the above benefits of dead trees are reduced or eliminated by our common forest management practices. Sanitizing a forest by “thinning” to promote so-called “forest health”, post-fire logging of burnt trees , or removal of beetle-killed tree bankrupts the forest ecosystem. And even our mostly ineffective efforts to suppress wildfires and/or feeble attempts to halt beetle-kill reduce the future production of dead wood and leads to biological impoverishment of the forest ecosystem. Creation and recruitment of dead trees is not a loss, rather it is an investment in future forests.

If you love birds, you have to love dead trees. If you love fishing, you have to love dead trees. If you want grizzlies to persist for another hundred years, you have to love dead trees.

More importantly you have to love or at least tolerate the ecological processes like beetle-kill or wildfire. These are the major factors that contribute dead trees to the forest.

So when you see fire-blackened trees or the red needles associated with a beetle kill, try to view these events in a different light-praise the dead: the forests, the wildlife, the fish– all will be pleased by your change of heart.

Wilkinson on 4FRI

I thought it was interesting that High Country News published this piece, by Charles Wilkinson, a law professor at University of Colorado. Here’s a link to his bio. Historical note: yes, the same person who was on the Committee of “Scientists” for the 2000 Planning Rule, so he’s been following these issues for some time.

Below is an excerpt of the piece. You can also find it at here at the Summit Daily News (thanks, Bob Berwyn) and other papers where Writers on the Range is syndicated. Because HCN and the syndication reach many readers who are not following this issue, I think it’s important to take a look at what Wilkinson says- what most people (outside the area) will read about what’s going on. The stakes are high for a landscape scale collaboration, so it is interesting to follow this, even for those of us far removed. What is interesting to me is the continuing story/question that the FS is screwing up with its choice of contractor, or about to screw up (before the EIS is released..??). Do people really think that the FS would go back on the general agreements that they worked so hard, for so many years, to get?? Or is this about something else entirely?

This blog is one of the few places that we could actually have this discussion with the details and knowledgeable people involved, so I am hoping when the EIS comes out we can track it here. Also, I think it’s the proposed action we’re interested in and not the EIS, but I guess I’m being pedantic again. I like to keep those separate in my head because I think it helps clarity.

We have discussed the 4FRI selection of contractor before here on this blog. including here, here and here.

The first link discusses the FS reasons for selecting the contractor. Like I said in that post, there is plenty of wood around the SW and Interior West, if folks have a good business plan maybe they could take it and develop 4FRI II elsewhere?

But a red flag has gone up: On May 18, the Forest Service announced its choice of contractor for the 4FRI process — Pioneer Associates, whose representative for the project just recently worked for the Forest Service. This was the largest stewardship contract awarded in the agency’s history, and yet the agency bypassed the contractor most deeply involved in 4FRI, the one whose business plan was closely tied to the project’s unique provisions.

Several 4FRI organizations have strongly criticized the choice of Pioneer Associates, citing the inadequacy of its business plan. The Eastern Arizona Counties Organization, for example, detailed “glaring deficiencies” in Pioneer’s bid and concluded that the award was “not based on either economic or ecological merit.” What’s troubling to many observers is that the choice of contractor may indicate that traditional attitudes are tearing away at the agency’s support of 4FRI.

The Forest Service, with its long and rich history, has run into trouble with the public and Congress in modern times over two main issues: Its timber harvests for far too long were set way too high, and far too often the agency insisted on doing things its own way. This approach — “we are the experts” — persisted in spite of contrary public opinion.

Both problems have been alleviated over the past decade or so. The timber cut is way down. The Forest Service now touts its commitment to collaboration with citizen groups, an approach that is widely agreed to be preferable to litigation and top-down, federal decision-making.

Doubters in Arizona, however, see the recent selection of Pioneer Associates as a bad sign. Tommie Cline Martin, a Gila County supervisor, predicts that, given the chosen contractor, the Forest Service will follow the same path as in the past, and that means “cutting big trees before getting to the small stuff, which is the threat to our remaining sickly forests.”

In the next few months, the Forest Service will face a major test on 4FRI, perhaps the agency’s most ambitious and carefully prepared collaboration effort. The regional office in Albuquerque will release — probably in July or August — the draft environmental impact statement for the collaborative effort. Does the choice of contractor suggest a lesser Forest Service commitment to 4FRI? Will the draft EIS weaken 4FRI’s environmental safeguards?

An immediate sign of trouble ahead is the news that Pioneer failed to include in its bid any funding for the regular monitoring of restoration efforts, an essential activity for good public land management. Will the draft EIS insist upon monitoring that will meet the standard set by the collaborative effort? Another hallmark of 4FRI’s approach is its commitment to thinning small-diameter trees because they, and not the large-growth trees, constitute the fire hazard. Will the draft EIS continue that emphasis?