This weekend an article ran in the UK titled “The bonfire of insanity: Woodland is shipped 3,800 miles and burned in Drax power.” The article was written by David Rose and provides an additional look into the issue of cutting down forests in North Carolina, chipping those forests into pellets and then shipping those pellets nearly 4,000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean to be burned in the United Kingdom. Some previous NCFP posts on the topic are here, here, here, here, here and here.

Snip:

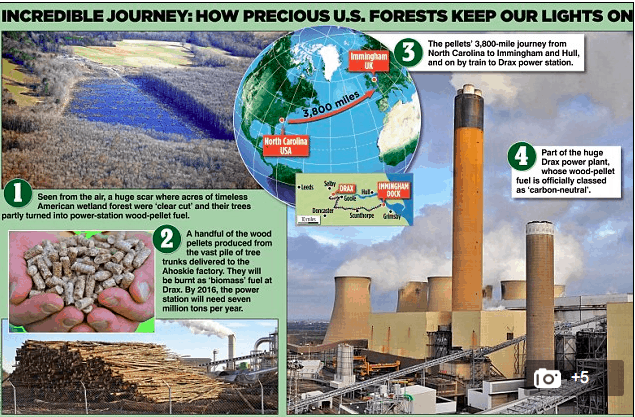

But North Carolina’s ‘bottomland’ forest is being cut down in swathes, and much of it pulped and turned into wood pellets – so Britain can keep its lights on.

The UK is committed by law to a radical shift to renewable energy. By 2020, the proportion of Britain’s electricity generated from ‘renewable’ sources is supposed to almost triple to 30 per cent, with more than a third of that from what is called ‘biomass’.

The only large-scale way to do this is by burning wood, man’s oldest fuel – because EU rules have determined it is ‘carbon-neutral’.

So our biggest power station, the leviathan Drax plant near Selby in North Yorkshire, is switching from dirty, non-renewable coal. Biomass is far more expensive, but the consumer helps the process by paying subsidies via levies on energy bills.

That’s where North Carolina’s forests come in. They are being reduced to pellets in a gargantuan pulping process at local factories, then shipped across the Atlantic from a purpose-built dock at Chesapeake Port, just across the state line in Virginia.

Those pellets are burnt by the billion at Drax. Each year, says Drax’s head of environment, Nigel Burdett, Drax buys more than a million metric tons of pellets from US firm Enviva, around two thirds of its total output. Most of them come not from fast-growing pine, but mixed, deciduous hardwood.

Drax and Enviva insist this practice is ‘sustainable’. But though it is entirely driven by the desire to curb greenhouse gas emissions, a broad alliance of US and international environmentalists argue it is increasing, not reducing them.

In fact, Burdett admits, Drax’s wood-fuelled furnaces actually produce three per cent more carbon dioxide (CO2) than coal – and well over twice as much as gas: 870g per megawatt hour (MW/hr) is belched out by wood, compared to just 400g for gas.

Then there’s the extra CO2 produced by manufacturing the pellets and transporting them 3,800 miles. According to Burdett [Drax’s Head of Environment], when all that is taken into account, using biomass for generating power produces 20 per cent more greenhouse gas emissions than coal.

And meanwhile, say the environmentalists, the forest’s precious wildlife habitat is being placed in jeopardy.

Drax concedes that ‘when biomass is burned, carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere’. Its defence is that trees – unlike coal or gas – are renewable because they can grow again, and that when they do, they will neutralise the carbon in the atmosphere by ‘breathing’ it in – or in technical parlance, ‘sequestering’ it.

So Drax claims that burning wood ‘significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions compared with coal-fired generation’ – by as much, Burdett says, as 80 per cent.

These claims are questionable. For one thing, some trees in the ‘bottomland’ woods can take more than 100 years to regrow. But for Drax, this argument has proven beneficial and lucrative.