This table is from Reilly, et al. I think this way of divvying up causes is helpful. I wonder if this is standardized anywhere?

This table is from Reilly, et al. I think this way of divvying up causes is helpful. I wonder if this is standardized anywhere?

I’ve often asked “how can we afford to fund studies that model wildfires in 2100 under different climate scenarios, but can’t afford the social science to help reduce human ignitions?”

Anyway, a big shout-out to Reilly et al. for their 2023 paper “The Influence of Socioeconomic Factors in Wildfire Ignitions in the Pacific Northwest USA”

On pages 2, 3 and 4, they have a roundup of other studies on the topic around the world, with links. I think it will be fairly interesting to Oregonians, especially how they talk about how different areas have different relationships between socioeconomic and physical factors and human-caused (as well as natural) ignitions.

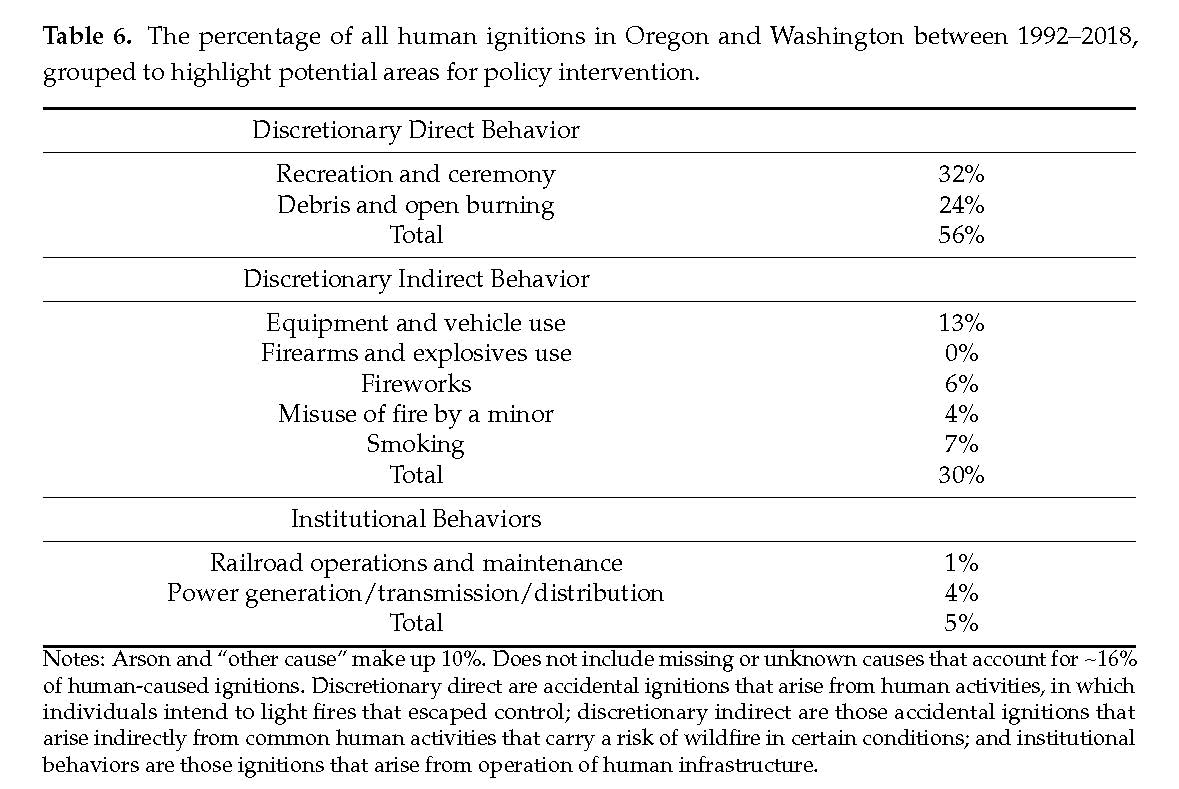

Maps of ignitions density (Figure 7) suggest that specific ignition causes exhibit unique spatial patterns. Higher densities of recreation caused ignitions were found along the west-side of Cascade mountain range and outside of urban centers such as Portland, Oregon,and Seattle, Washington, where recreation use is high (Figure 7a), and concentrations of ignitions attributable to debris and open burning were clustered in more rural areas immediately surrounding major cities and in the northeast region of Washington (Figure 7b).Ignitions caused by equipment and vehicle use (Figure 7c) were concentrated in the south-west of Oregon, where forestry and agriculture activity intersected with the areas of higher wildfire hazard potential. These patterns were further explored with spatial hotspot analysis, which indicated that these clusters of county subdivisions with high human ignition density were statistically significant (Appendix B, Figures A1 and A2).From a policy and management perspective, it may be useful to consider how interventions might be designed and deployed to address behaviors that lead to ignitions of unintended human-caused wildfires (Table 6). Given that discretionary direct behaviors(recreation and open burning) generated over half of the known causes of human ignitions(56 percent) in Oregon and Washington over the past quarter century, it may be prudent to develop more tailored information and outreach programs that guide risk assessment of these activities under high risk fire weather conditions geared towards recreationists or for those applying for burn permits and to target interventions to the most relevant areas. Similarly, the development of tailored information regarding wildfire risk of common discretionary indirect activities could help reduce the number of ignitions resulting from activities such as vehicle and equipment use, the third largest known cause of human ignitions in the region

**********************

Last year, Axios San Diego had an interesting story on human caused fires in California

By the numbers: About 86% of wildfires in California between 1992 and 2020 were spurred by human activity, burning 63 acres on average, U.S. Forest Service analysis of wildfire data found.

- Meanwhile, Cal Fire officials say 95% of fires are human-caused currently.

Of note: Lightning strikes accounted for the other fires with known causes, mostly in the northeastern and mountainous parts of the state that border Nevada.

- Lightning strikes were behind California’s largest fires, which took place in August 2020, burning more than 2 million acres combined — that’s about three-quarters of the size of San Diego County.

Details: The top three human activities known to have led to these blazes were from equipment and vehicles, arson and debris burning, the data shows.

- That includes accidental incidents and neglect, such as leaving a campfire unattended or a malfunctioning catalytic converter spitting a molten substance out of an exhaust pipe.

Between the lines: While firearms and explosives caused 0.2% of wildfires, they led to the largest human-caused blazes, at 380 acres on average.

*******************************

The Hotshot Wakeup reported that Arizona folks are beginning to investigate and address human-caused wildfire ignitions. The ones in Pinal County seem to be focused on using equipment in the wildland-urban interface in areas with greater fuel loadings than people are used to.

“Our last seven starts have been human-caused and they have actually been construction companies starting these,” Scottsdale Fire Capt. Dave Folio said.

The department is asking those construction crews to create a 10 to 15-foot defensible space around their work areas.

Folio says we have seen how dangerous not taking these precautions can be.

Last June, the Diamond Fire, which was caused by a construction crew cutting rebar, forced 1,000 people to leave their north Scottsdale homes as the flames got within feet of properties.

“Construction crews choose a place to cut the rebar that isn’t in the middle of the desert,” Folio said. “Move the combustibles off your construction site. Help us eliminate one spark and that’s all we’re asking for.”

Meanwhile, the Tonto NF reported human-caused fires from recreational uses.

In many cases, human-caused fires could originate from target shooting, fireworks, Off-Highway Vehicle (OHV) use or other vehicle fire, escaped campfire, accidentally or intentionally set. Human-caused fires outnumber natural starts by 3 to 1 on the Tonto, with several already this season such as the Spring Fire, related to target shooting, and Wildcat fire, related to OHV use.

****************

For many areas, it’s the beginning of the fire season, but please add links where you find local concerns about human-caused fires and what the locality is doing to reduce them. Smokey’s back!

I found it interesting after the Forest Fire Districts in SW Oregon starting putting automated smoke detection cameras on their existing lookouts that they caught a lot of un-permitted burning going on. Hopefully that has led to fewer human-caused fires where those cameras have been installed!

Thanks, A! Do you know if they reported that un-permitted burning and some kind of action was taken?

Maybe they’ll have to add a category for YouTube stunts.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/youtuber-alex-chois-wacko-lamborghini-stunt-ends-in-federal-charges

Almost all major fires in SW Oregon since the 1987 Silver Complex — with the notable exception of the deadly 2020 Almeda Drive Fire — were started by either lightning or USFS backfires. For the 500,000-acre 2002 Biscuit Fire, for example, I’ve been informed that as few as 20,000 acres were set by USFS, but also told that more than 200,000 acres were the result of backfires. Not sure if there is a straight answer, but the problems are lightning and federal wildfire management, not local people burning brush or having bonfires. Mostly a result of poor fuel management practices since the Kalmiopsis was created in the 60s.