As the election campaign overheats, here are a couple critiques of current Biden and future Trump policies affecting the Forest Service.

WildEarth Guardians recently reviewed a FY 2022 Forest Service Report to Congress, which discusses “timber program performance.” (I’d note that the context was “the unexpected increase in demand for lumber during the recent period of quarantine and social distancing due to the coronavirus pandemic…”) WildEarth Guardians said,

The document outlines how the agency can increase logging in our national forests by at least 25 percent above current levels, to four billion board feet each year! The last time the Forest Service sold that much timber from our national forests was 1993, the year the agency started developing the Northwest Forest Plan to address habitat loss for the northern spotted owl caused by—that’s right—overlogging. That level of logging was not sustainable then and it isn’t sustainable now, especially in light of what we know now about the importance of protecting mature and old-growth forests to mitigate the effects of climate change. Nevertheless, the Forest Service wants to turn the clock back and actually spells out just how it wants to do that.

The remedy, according to the Forest Service, is not to stop proposing ecologically damaging timber sales that violate the law, but rather to ask Congress for “legislative fixes” that make it harder, if not impossible, to challenge ecologically damaging timber sales in court. Streamlining environmental reviews and limiting public input, the Forest Service says, “will help increase timber volume sold.”

We shouldn’t wonder why there is skepticism from these parts when the Forest Service says “trust us.” As WildEarth Guardians summarized (with their emphasis):

Such perverse incentives are a stark reminder that timber production remains the overarching priority for the Forest Service while all other values, like wildlife or climate mitigation, are a distant second. As the Forest Service seeks to push timber production levels even higher, those of us who care about our national forests must be ready to speak up and tell the agency and lawmakers that we cannot turn the clock back to a time when unsustainable logging pushed species like the northern spotted owl to the brink of extinction.

An article in the Huffington Post focused on the Department of Interior (but has implications for national forests), and indicates the incentives would be even more perverse for management of our public lands under Trump II, requiring even more public oversight (if they don’t take away the ability to do that):

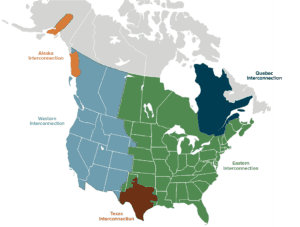

Pendley’s blueprint for Trump, if he should win in November, includes holding robust oil and gas lease sales on- and offshore, boosting drilling across northern Alaska, slashing the royalties that fossil fuel companies pay to drill on federal lands, expediting oil and gas permitting, and rescinding Biden-era rules aimed at protecting endangered species and limiting methane pollution from oil and gas operations.

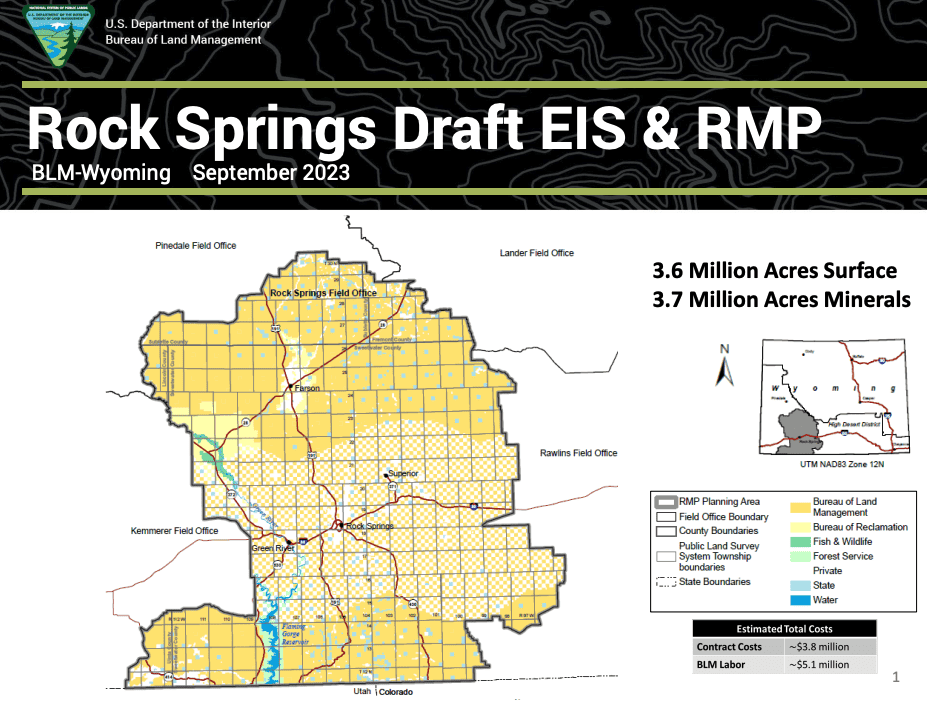

Along with a series of actions to boost drilling and mining across the federal estate, Pendley calls for a future Republican administration to not only dismantle existing protected landscapes but limit presidents’ ability to protect others in the future. He advocates for vacating Biden’s executive order establishing a goal of conserving 30% of federal lands and waters by 2030; rescinding the Biden administration’s drilling and mining moratoriums in Colorado, New Mexico and Minnesota; reviewing all Biden-era resource management plans, which cover millions of acres of federal lands; and repealing the Antiquities Act, the landmark 1906 law that 18 presidents have used to designate 161 national monuments.

If that reads like a fossil fuel industry wish list, it’s because it is. Rather than personally calling for the keys to America’s public lands to be turned over to America’s fossil fuel sector, Pendley let the head of a powerful industry group do it for him.

“Beyond posing an existential threat to democracy, Project 2025 puts special interests over everyday Americans,” said Tony Carrk, executive director of Accountable.US, a progressive watchdog group that shared its research on Project 2025 with HuffPost. “The dangerous initiative has handed off its policy proposals to the same industry players who have dumped millions into the project — and who will massively benefit from its industry-friendly policies.”

“They could have found any number of mainstream conservatives to write their agenda for them. They didn’t,” Weiss said. “They picked the notorious anti-public lands extremist, because that is at the end of the day what they want.