I’m not following the Northwest Forest Plan update.. fortunately many members of the TSW community are tracking it and hopefully will provide us with updates. But when I read this paper (open access), it made so much sense to me that I thought it was worth sharing. It’s about how the Bureau of Reclamation, one of the Forest Service’s many cousin DOI agencies, deals with the complex world of uncertain futures, climate change being one of many. Not only that, but even if we could project future microclimates accurately (which we can’t), we don’t know how climate changes will cause different interactions with hydrology, temperature, plants, animals, the rhizosphere, insects, diseases, etc. So there are different ways of planning based on acknowledging uncertainties. And yet at some point, the modeling and scenario-building with acknowledged uncertainties could get so complex that no single person could possible understand it. And how can the public effectively be involved in that case?

I’m not following the Northwest Forest Plan update.. fortunately many members of the TSW community are tracking it and hopefully will provide us with updates. But when I read this paper (open access), it made so much sense to me that I thought it was worth sharing. It’s about how the Bureau of Reclamation, one of the Forest Service’s many cousin DOI agencies, deals with the complex world of uncertain futures, climate change being one of many. Not only that, but even if we could project future microclimates accurately (which we can’t), we don’t know how climate changes will cause different interactions with hydrology, temperature, plants, animals, the rhizosphere, insects, diseases, etc. So there are different ways of planning based on acknowledging uncertainties. And yet at some point, the modeling and scenario-building with acknowledged uncertainties could get so complex that no single person could possible understand it. And how can the public effectively be involved in that case?

The Forest Service is legally required via NFMA to do long-range planning (although the RPA Program seems to have fallen by the wayside). The question is “what is the variety with which agencies approach the use of climate as well as other uncertainties in decision-making?” Are they consistent (even within a department)? Should they be? Are some approaches better than others? Based on what criteria?

I kind of like this approach; at least it might be worth a try in a pilot. Or perhaps the Northwest Forest Plan revision?

Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty

A focus on vulnerability, robustness, and adaptation necessitates an expansion of analytical methods beyond those traditionally used in long-term water resources planning. Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty (DMDU) is a subfield of decision science that focuses on developing and applying the frameworks, tools and techniques necessary to produce actionable information while appropriately accounting for deep uncertainty (Marchau et al. 2019). Models have long been used to answer “what-if” questions (Bankes et al. 2013) and have been widely adopted in many planning contexts, including in the Colorado River Basin. DMDU builds on this model-informed decision making by helping planners strategically design the “what ifs” and offering new quantitative tools to drive models and analyze output. Since the early 2000s, a dedicated and rapidly growing community of researchers and practitioners forming the Society for DMDU (http://www.deepuncertainty.org) has been applying and refining DMDU methods in a wide range of domains including national security (Dixon et al. 2008), energy planning (Toman et al. 2008), and water resources management (Lempert and Groves 2010; Means et al. 2010; Basdekas 2014; Raucher and Raucher 2015; Groves et al. 2019).DMDU techniques share a common underlying philosophy of designing iterative planning processes and analyses to identify actions that reduce a system’s vulnerability to uncertain future conditions. Robust Decision Making (RDM) (Lempert 2002) is described here as an example because Reclamation has used components of it in the past and is continuing to explore and develop related methods.

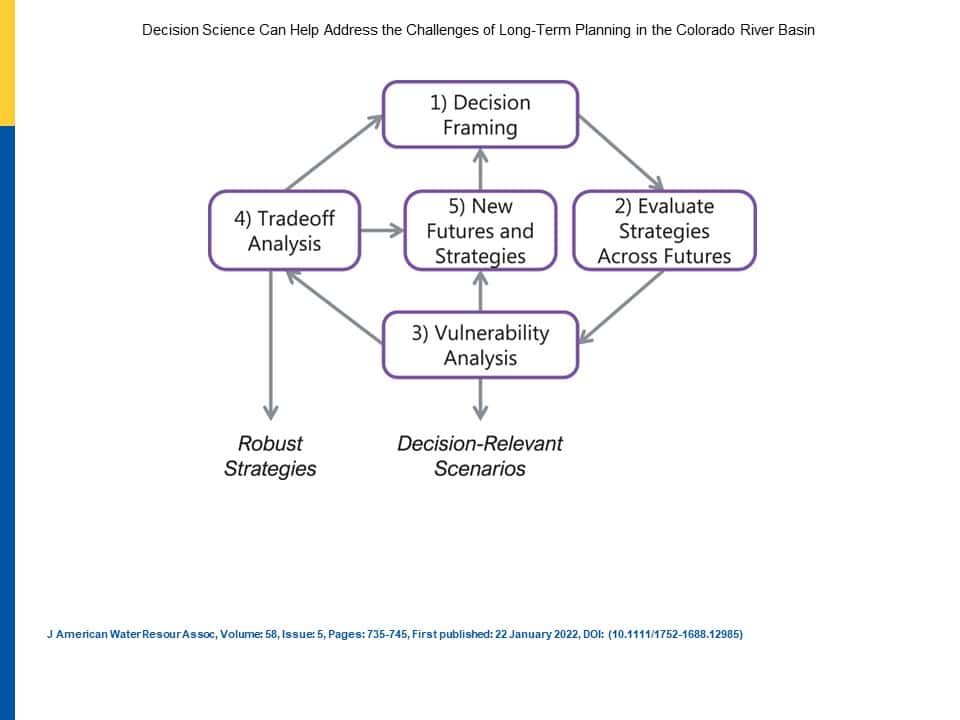

RDM is designed to facilitate a “deliberation with analysis” process through which parties can systematically integrate a large amount of information and wide-ranging positions about possible future conditions, important performance objectives, and appropriate actions to address challenges. The ultimate goals of RDM are to develop shared understanding of a system and identify a broadly acceptable plan or policy that is robust to a range of futures. The steps of RDM are depicted in Figure 3 and summarized below. Note that although the steps are numbered here and described in order, in practice the relationships between the components of RDM are flexible.

In Step 1, stakeholders define key components of the analysis: performance objectives and criteria; the sets of possible actions, or strategies, that could be undertaken in pursuit of the objectives; ranges of values for uncertain future conditions; and a model that simulates relationships between objectives, actions, and uncertainties. In Step 2, a proposed strategy is tested in a wide range of future conditions to generate a thorough representation of performance variability. In Step 3, the performance information is analyzed with statistical data mining techniques that seek to “discover” decision-relevant scenarios, or those combinations of uncertain conditions that cause the strategy to perform poorly. (This is a departure from traditional analysis in that the scenarios themselves are not dictated in advance of the procedure.) In Step 4, tradeoffs with respect to robustness, vulnerabilities, and costs among different strategies are analyzed, and a single strategy may be agreed upon. If insights from Step 3 or Step 4 warrant it, Step 5 may be necessary to reframe the decision and develop new strategies, at which point the RDM process repeats.