The rusty-patched bumblebee and Franklin’s bumblebee have been listed under ESA and other species are being considered. The Xerces Society considers 11 species of bumblebee to be at-risk. The Forest Service and BLM allow special use permits for non-native honeybee apiaries on their lands based on categorical exclusions. Here is the one applicable to the Forest Service (36 CFR 220.6(d)(8)):

(8) Approval, modification, or continuation of minor, short-term (1 year or less) special uses of National Forest System lands. Examples include but are not limited to: (i) Approving, on an annual basis, the intermittent use and occupancy by a State licensed outfitter or guide; (ii) Approving the use of National Forest System land for apiaries; and (iii) Approving the gathering of forest products for personal use.

The science? According to this article:

Most scientists agree that honeybees are not native to the Americas. They were imported to the continent in the 1600s on cargo ships from Europe and arrived in Utah in the mid-1800s.

Honeybees tend to outcompete native bees for pollen. Tepedino said, “if you put enormous numbers of honeybees on public lands … the native bee population must, by necessity, be deprived.”

A study by Tepedino concludes that the honeybees in a single apiary can, in just four months, remove enough pollen to raise five to 13 million native bees.

O’Brien said that competition is also worsened by climate change. Because climate change leads to more drought and as a result fewer flowers, it is becoming more difficult for native bees to compete with honeybees, she said.

Mary O’Brien (a botanist) also said the CE was instituted in the 1980s, before scientists knew very much about native bees. She points to the western bumblebee, a species she said is “critically imperiled” in Utah. It is particularly threatened by diseases, including ones that are transmitted by honeybees.

Project Eleven Hundred was born about five years ago in response to a request for a permit to place 100 hives each at 49 sites in the Manti-La Sal National Forest. That permit was denied, but there is currently a permit on the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest that is up for renewal at the end of this year, which is being contested and may be litigated. Project 1100 has also petitioned to remove the CE.

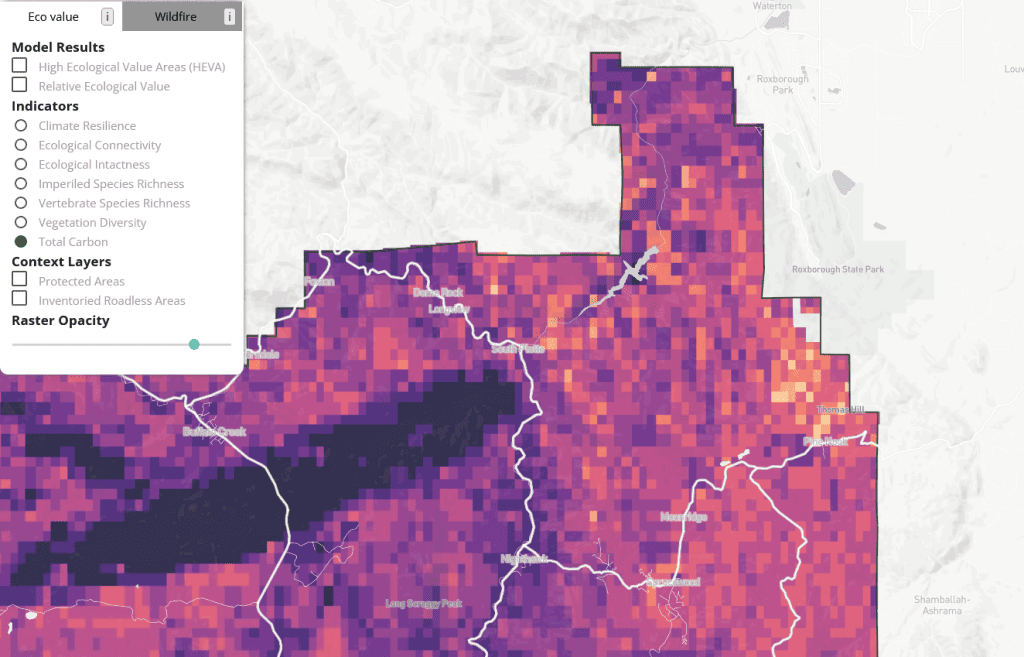

In forest planning under the 2012 Planning Rule, species of conservation concern are to be designated SCC if there is a risk to their persistence in the plan area. Both listed species and SCC must be addressed in forest planning to ensure that the plan decisions (components) adequately protect these species from threats. Since commercial non-native apiaries are a threat to these species, a forest plan should consider, and probably adopt standards that regulate or prohibit issuance of permits for honeybees. (I’m guessing wild honeybees are found on most national forests.)

The proposed revision of the Manti-La Sal National Forest Management Plan allows apiaries, subject to a standard stating that permits “shall not be issued for placement of hives within 5 miles of known insect-pollinated, at-risk plant species locations or at-risk insect populations.” It also states that a maximum of 20 hives can be issued for each apiary special use permit (which is arguably “not commercially viable”). O’Brien said this is an impossible precaution to enforce. “As if they know where [native bees] are,” she said. “…The western bumblebee would be considered at risk, and they don’t know where it flies.”

The western bumblebee was NOT designated as an SCC in the Manti-La Sal’s draft of its revised forest plan.