Thanks to a TSW reader for this story. This fits into our ongoing theme of housing difficulties and the exodus of the working class in some Western communities. And if the economy is based on tourism, which doesn’t have high-paying jobs in general, it seems like these communities may be moving to a two-tier society. Perhaps with lower-end retirees and work-from-homers in the middle. Also there is the idea that at some point, with these kinds of pressures, the timber industry could go belly-up just when people are coming around to it being helpful in keeping fuel treatment material from being burned into the atmosphere. Meanwhile we have a housing crisis in many areas, more people are moving to these places (both migrants from other states and other countries), and wood is needed as a building material. And we don’t want new communities to “sprawl,” (get larger), so densification is cool, and yet ideas like Accessory Development Units don’t allow people to build equity via ownership. And many increases in density come with decreases in urban trees. Reminds me that old Thomas Sowell quote “there are no solutions, only trade-offs.” But is anyone looking at the big picture here?

It seems like a tangled ball of policy yarn, with no clear loose end to begin to unravel it.

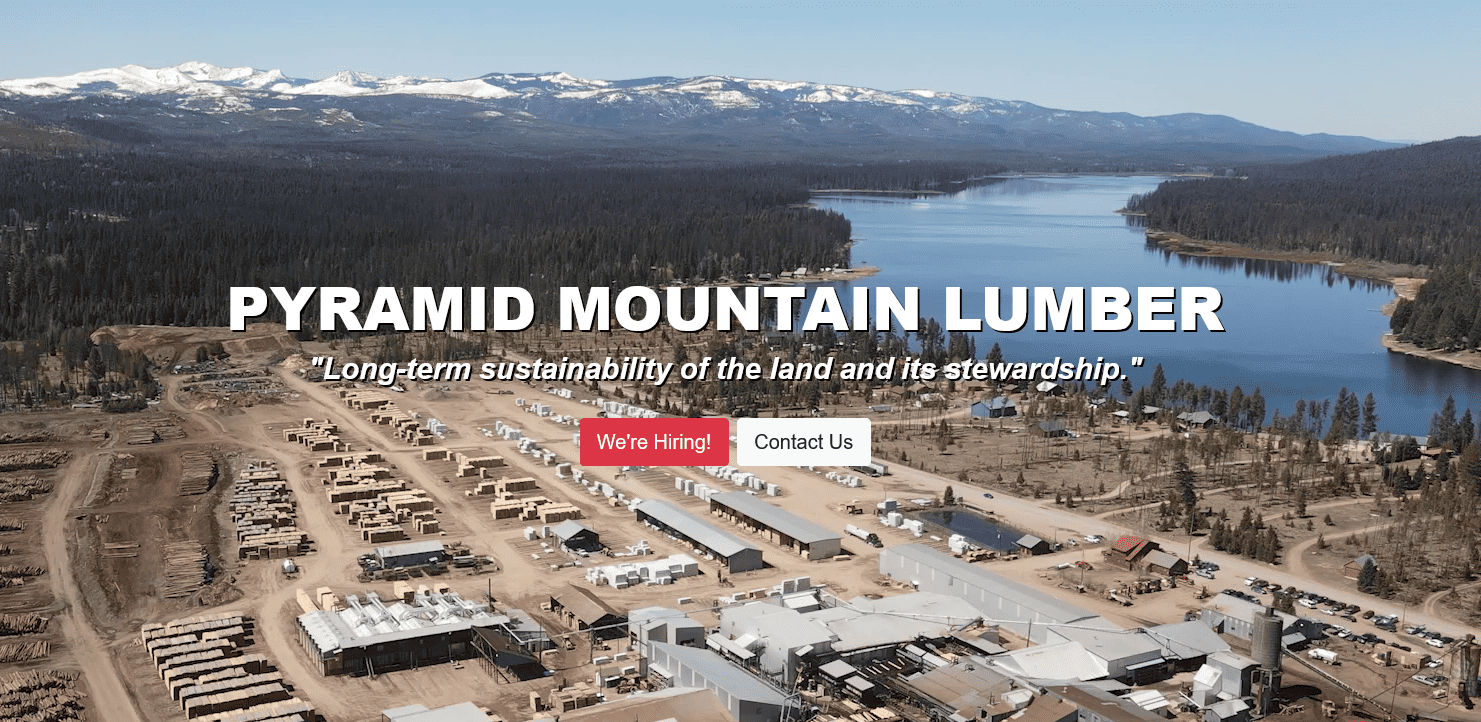

Over the last five years, a “Now Hiring” sign has been posted along U.S. Highway 83, and the starting wage at Pyramid has been creeping up, Browder said.

He said other workers will be affected as well, such as loggers who are independent contractors and brought raw mateerial to Pyramid.

But he said getting mill employees and finding them places to live is difficult.

Housing creates costly employee attrition, because the company might train a worker who only stays six or eight months, Browder said: “That person leaves because they’re living in some crappy little trailer.”

He said it’s a problem for smaller merchants and retailers, too.

“We just have a serious housing problem in Seeley Lake, and it doesn’t just affect them,” Browder said of Pyramid.

The “blue collar demographic” will take a hit as a result, and Browder said he isn’t sure what young mill workers or couples will do instead because there’s little else in western Montana for them.

“All the working class people are being squeezed out,” he said.

Tourism has become a larger part of the economy, and more retirees who don’t rely on a local job for their income are part of the change in Seeley Lake, Browder said. But he volunteers at the food bank, and he said he anticipates a spike in demand there.

Generally, he said, attendance at community council meetings is low, and he hopes the news will at least bring more people with new ideas to the discussions.

**********

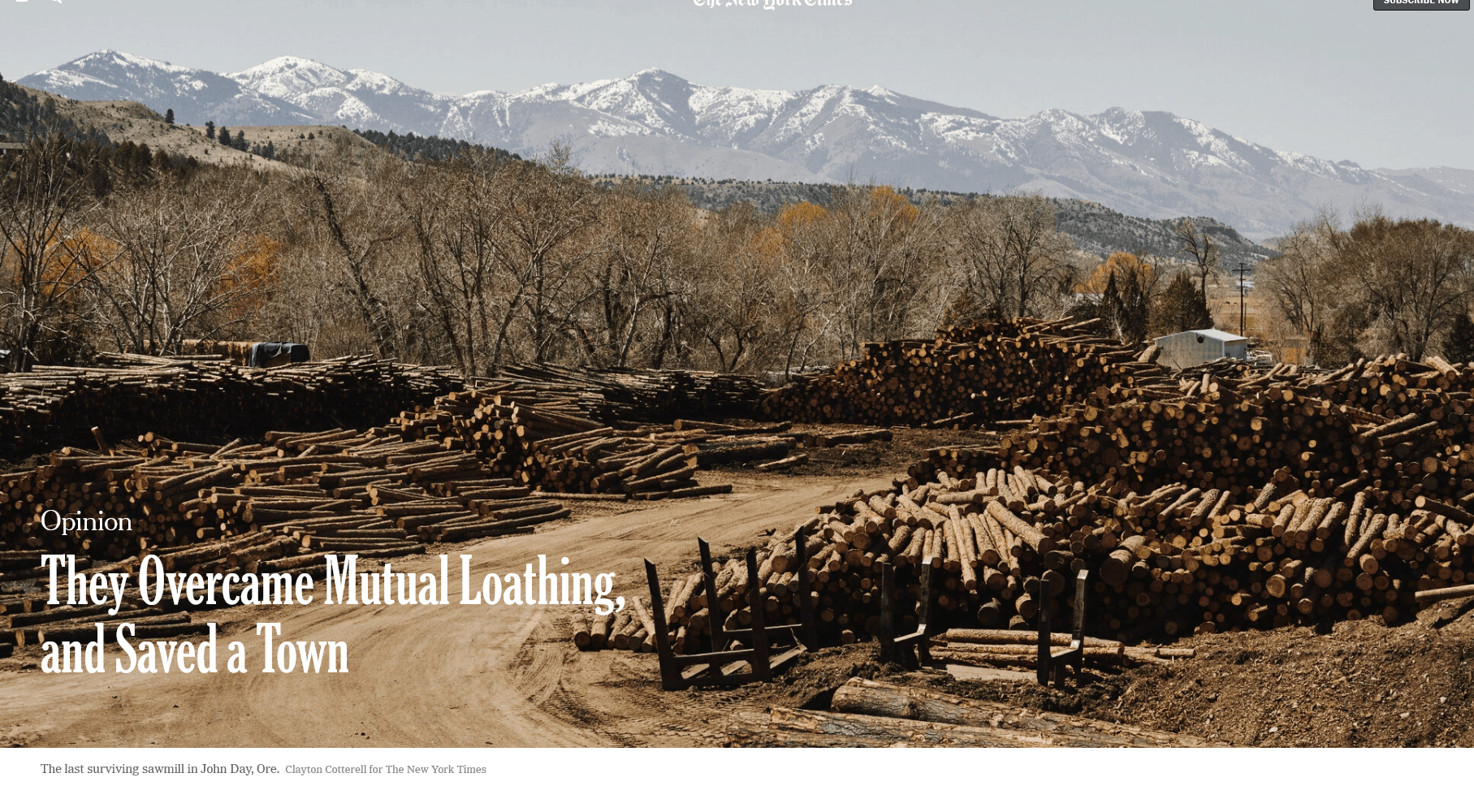

Kier, with the Missoula Economic Partnership, said if the mill closes, it will have ripple effects on the wood products and forest industry. He said he believes the Seeley Lake mill is one of the few that takes Ponderosa logs, which are plentiful in the region.

A couple of other businesses in Montana depend on byproducts from the mill, he said, including Roseburg in Missoula, which produces particleboard, and Weyerhaeuser in Kalispell, which offers plywood panels, among other products.

“Having adequate supply is important for those large manufacturers in terms of a regional system,” Kier said. “So it’s a really fragile system right now.”

He said it’s clear Pyramid intends to shut down, but a lot of people are emerging “by the hour” and talking about whether options exist for others to keep the facility open given it’s an important part of managing healthy forests. But Kier said it’s “premature to suggest there’s any real solution.”

“I hope that the folks who are in Seeley and the folks who are working at the mill know a lot of people care about what is happening to them,” Kier said.

In their closure announcement, Pyramid said “there’s no better solution” for the owners than to shut down the mill permanently. They were advised to close it in 2007 and didn’t, but this time, they said, the financial crisis is worse.

“The owners would like to thank our employees, both past and present, for their hard work and professionalism over the years,” Pyramid said.

“Their dedication has truly been the difference between Pyramid and its competitors. The owners would also like to thank Seeley Lake and the surrounding communities for their support over the years.”