Here’s a little more (added to this) on the Nez Perce-Clearwater revised forest plan. Mostly I wanted to share this graphic of how they are “reaching out” to the public. They ask an important question: “What can you do?” The obvious meaning seems to be what can you do about the forest plan, and the answer for most people is “nothing.” They say that the plan is in the objection period, but don’t tell us that the only people who can participate are those who have already done so. They invite us to “learn more,” about this nearly-done deal, which they misleading label as a “draft Forest Management Plan.” (At the draft EIS stage, the Planning Rule refers to it as the “proposed plan,” and at the objection stage it is just the “plan.) While they have must have included similar outreach at earlier stages in the process, for those encountering this for the first time, it’s almost disingenuous.

But while I’m at it , there was also another article recently that focused on the State Line Trail, which runs through the Hoodoo Recommended Wilderness Area in the Great Burn between Idaho and Montana. (I’ve been there but haven’t been directly involved in the planning, so know only what I read.)

“It used to be a marquee backcountry ride for mountain bikers, too. That ended in 2012 when the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest, which controls the Idaho side of the trail, approved a new travel management plan that barred bicycles from its portion of the trail. On the Montana side, the Lolo National Forest has long allowed bicycles on the trail.”

A new revised forest plan for the Nez Perce-Clearwater could change that, by determining that bicycles are an appropriate use in the portions of Idaho around the trail, which would mirror access on the Montana side. If the changes in the plan are finalized, possibly later this year, that would set the stage for the Nez Perce-Clearwater to revisit and alter its 2012 travel plan to formally re-allow bicycles on the trail.”

The rationale behind these changes, according to the forest supervisor, don’t seem to include consistency (more on that later): “We have these types of very primitive, amazing, out in the middle of nowhere experiences that you can get to no matter what your matter of conveyance is.” No apparent agency recognition that the conveyance is part of the experience for those who encounter it, and for some it makes it feel unpleasantly more like “somewhere.”

One of the supporters added, “It’s a small segment of the sport that this is going to appeal to,” he said. “It’s not that close to Missoula. It’s hard. The trail’s in deteriorating condition. But this opportunity is, for certain people, something they really, really want.” That small segment of certain people (who apparently want to deteriorate the trail even more) must be pretty special to get this kind of personalized attention.

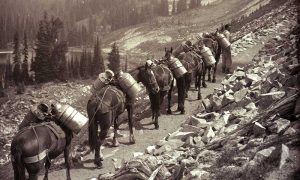

“Some mountain bikers are drawn to remote, rugged, and challenging backcountry trail experiences on wild and raw landscapes,” a group of supporters commented. “These are places where it is uncommon to see other trail users, and where riding requires a high level of physical fitness and technical skill — in many cases it involves pushing a bike instead of riding at all.” That would be like hiking, wouldn’t it? So, it’s not like closing the area to this use would exclude these physically fit people from these wild and raw landscapes. I’ll admit that I don’t understand the rationale of wanting to experience a “wild and raw landscape” on a machine, which (to me) reduces the rawness and wildness of the experience.

The aura of personal opinion and politics behind these wilderness debates is why I focus my energy on other things. Here there is also talk about snowmobiles and mountain goats, and why mountain goats are treated differently in adjacent national forests.

As for the effects of snowmobiles on mountain goats, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game blamed them for disappearance from one part of this area, but the founder of the Backcountry Sled Patriots says otherwise (citing other research). The Lolo National Forest cited the negative effect of motorized over-snow machines as reason for designating them a species of conservation concern. The Nez Perce-Clearwater is not concerned about mountain goats. The Forest Service minimizes the importance of the areas at issue to mountain goats (though they apparently used to be some places they are not found now).

About the Lolo, Marten, the regional forester, who determines which species are SCC, wrote:

“Compared to other ungulates, the species appears particularly sensitive to human disturbance. Motorized and non-motorized recreation, as well as aerial vehicles, are well documented to affect the species, particularly during winter and kid-rearing season, with impacts ranging from permanent or seasonal (displacement), to changes in behavior and productivity.”

The regional director for ecosystem planning said that she didn’t see the different listing decisions as being in conflict with each other. Rather, she said, they reflect that mountains goats are doing better overall on one forest than the other. This may be technically/legally possible since SCC are based on persistence in an individual forest plan area. However, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to me to manage one national forest to increase the risk to, and to contribute to SCC designation on, another forest. Moreover, the Planning Handbook states that “species of conservation concern in adjoining National Forest System plan areas” should be considered by the regional forester in making this designation. This all has kind of an arbitrary ring to it.

As for consistent management across national forest boundaries, The Nez Perce-Clearwater plans to change the shape of the Hoodoo RWA to remove the key snowmobile areas from it, so that boundary between the national forests becomes a boundary for the RWA. The Forest Service points out that the plan revision process in the hands of forest supervisors, not the regional office. The forest supervisors disclaim any obligation for consistency, and even suggest that travel planning may produce a different result, and “forest plans and travel management plans are continually updated and amended” so they could change again. That doesn’t square well with history. The every-third-of-a-century Forest plan revision should be the time to get it right. Even if the regional forester doesn’t want to say what the plans must do, that person could simply order them to be consistent along this boundary.