From the News-Review, Roseburg, OR:

Lone Rock Timber Management Company has asked the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office for additional patrols in response to a threat made against the company by conservationists, according to the sheriff’s call logs.

The call, made just before 6 p.m. Thursday, said a group of conservationists are upset that Lone Rock is logging in the Susan Creek area, land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, and are threatening to burn Lone Rock “to the ground.”

Doesn’t mention the name of the group.

[ADDITIONAL INFORMATION BELOW, POSTED BY MK]

Posted on Facebook on May 7, 2018 by Francis Eatherington:

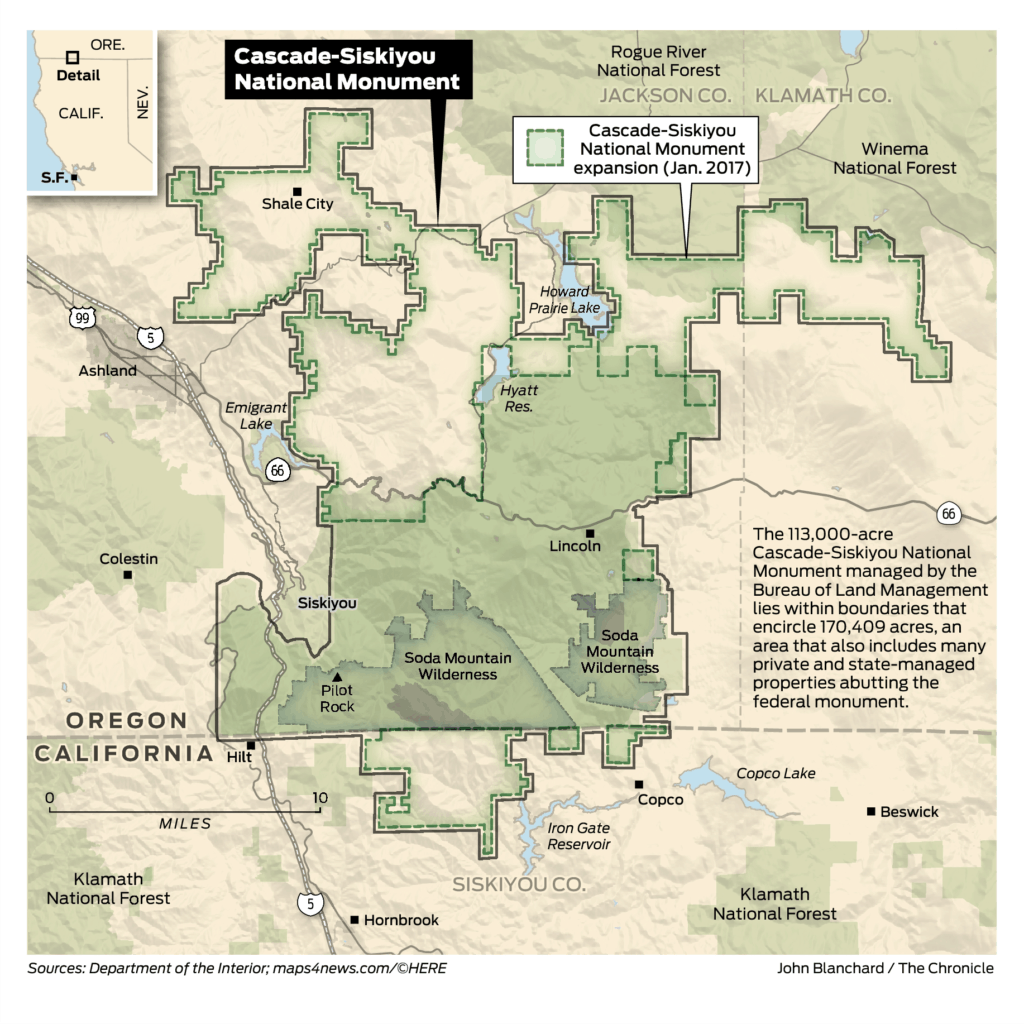

“Yesterday we hiked into the BLM forest that Lone Rock Timber had threatened to cut down for a new road, and we found it just cut down. Very sad. All the big trees were horizontal on the ground. We counted the rings on some stumps and found them to be 400 years old. On the hike in we went past LRT’s 19-acre plantation they had just cut and yarded, and we could see about an acre of tiny trees they had left to cut at the top of their unit. Even though it was clearcut 40-years ago, this time LRT insisted they had to cut this 70’-wide road through BLM land to get a mechanical harvester into that little acre they had left. They couldn’t cut it manually like they did before. This is an obvious scam by Lone Rock – they will get far more timber from our public old growth forest then they will access from their land. Not only are the old-growth trees gone, a new road bulldozed across this ancient forest will be a horrible scar, spreading it’s edge-effect far into the remaining old growth forest.”

Posted on Facebook on May 7, 2018 by Doug Heiken:

“The reason that Lone Rock Timber gave for needing access through this stand of ancient trees, was they needed to get a mechanical harvester (tree killing robot) into the area so they could log a stand of small trees on their own land. However, before the road even got built Lone Rock was able to log all but about 1 acre of their land. Which means these ancient trees fell just so they could bring their robot in to fell an acre of second growth. This is SO wrong! I smell a scam. The timber industry is to blame and BLM is complicit.”

[ADDITIONAL INFORMATION BELOW, POSTED BY SF]

Here seens a fair-minded piece that looks at (and talks to) both sides (and explains the O&C rights of way). But be careful, as there are a couple of interesting stories and you only get five free ones.

In this case they claim that BLM has embarked on a ‘back-room deal with Lone Rock Timber to log ancient forests,’ when the truth of the matter is that Lone Rock Timber has the legal right under our reciprocal right-of-way agreement with the BLM to construct the road to gain access to our property,” Luther said, adding some of the trees in the posted photos are outside of the proposed logging area.

If I lived in the area, I would be tempted to go see for myself (and share the photos here).

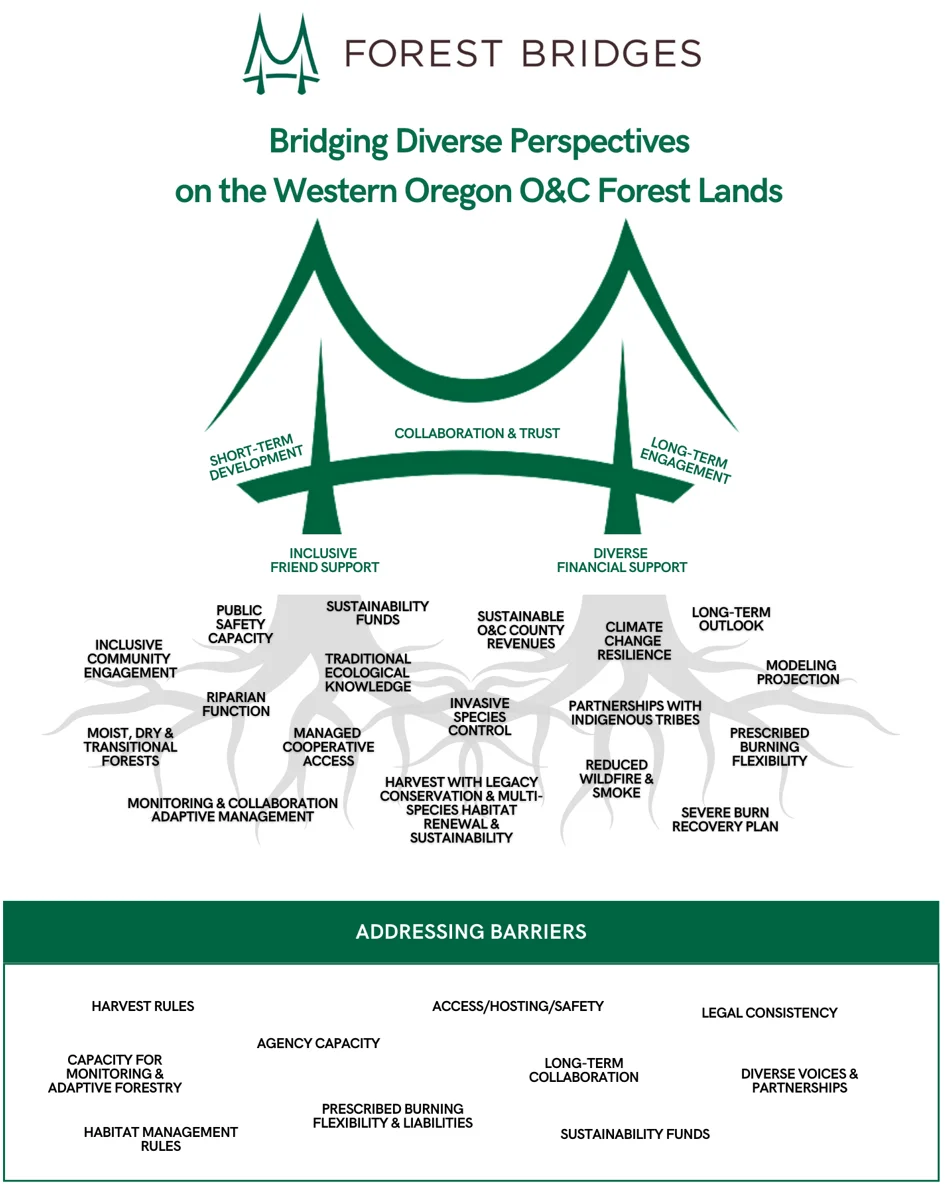

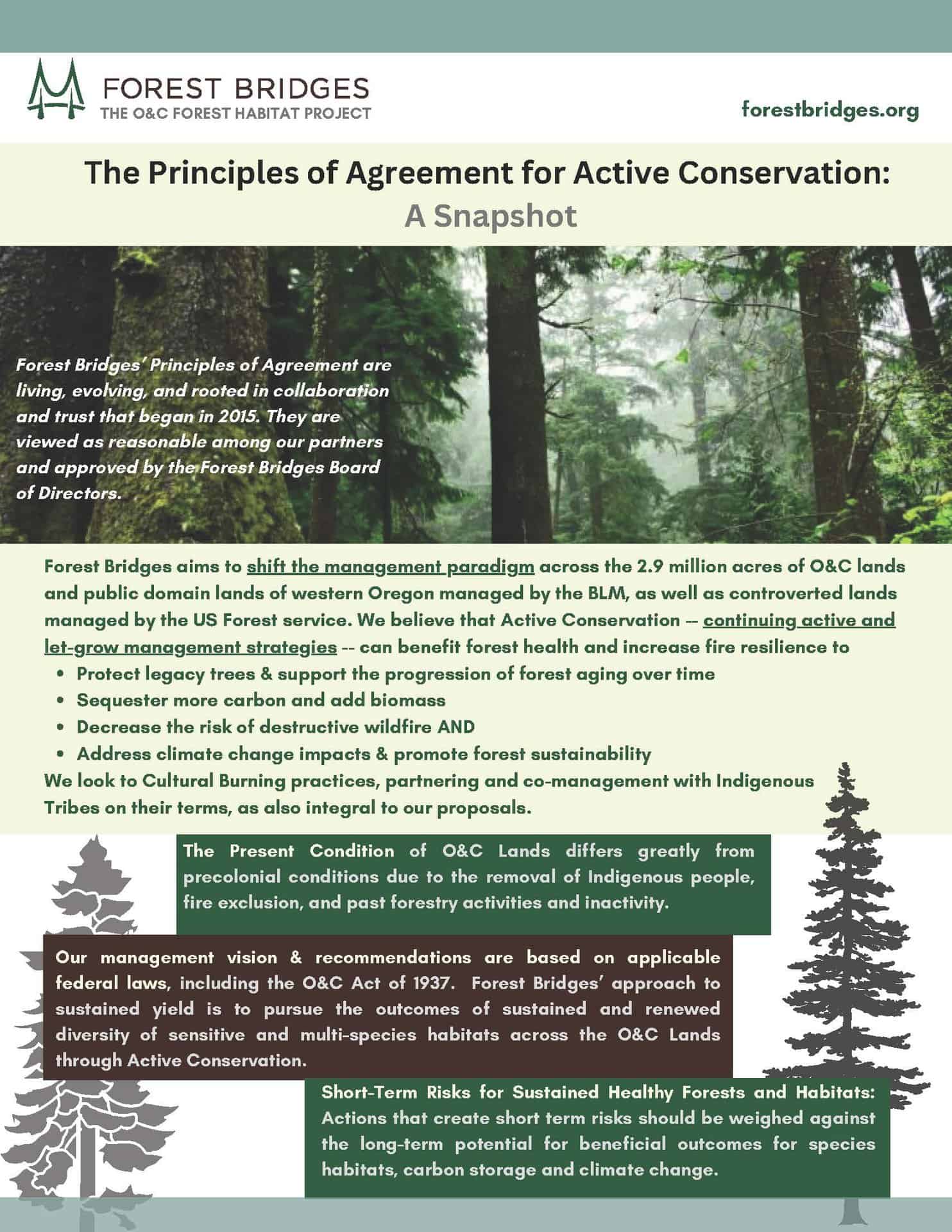

I’m always interested in people seeking agreement about forest issues, and Oregon seems to be a long-time source of ongoing controversy. Thanks to Nick Smith for this one.

I’m always interested in people seeking agreement about forest issues, and Oregon seems to be a long-time source of ongoing controversy. Thanks to Nick Smith for this one.

Below is a snapshot of their principles of agreement. Feel free to discuss anything on the website in the comments.

Below is a snapshot of their principles of agreement. Feel free to discuss anything on the website in the comments.