This book apparently goes into many topics of interest that have been frequently discussed by TSW readers. I found this review on The Society of Environmental Journalists page. Would anyone like to review the book for TSW readers? I have to wonder about how these concepts track with abstractions like “ecosystem integrity” or the more recent BLM idea “health of the landscape” (at least with reference to grazing rules) as Steve quoted here. I have to say it’s much easier for me to think about the question of “what is the appropriate level of intervention?”under the abstraction of “climate resilience.”

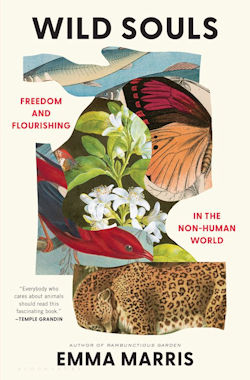

BookShelf: ‘Wild Souls’ Explores Paradox of Managing Species To Save Them

“Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World”

By Emma Marris

Bloomsbury, $28.00

Reviewed by Jennifer Weeks

A decade ago on a family trip to the Grand Canyon, my 7-year-old daughter spotted a signboard as we walked along the South Rim: “Condor presentation here at 3:00.”

“Look, a condor is coming!” she said.

We had mentioned that they were one of the region’s rarest species and were clawing their way back from the brink of extinction.

I started explaining that the sign meant a ranger was going to give a talk, not that he or she would bring a condor — they were wild and free-flying, not on display.

As I was in mid-sentence, a huge shadow fell across the sidewalk.

Everyone along the path looked up and started taking pictures of, yes, a California condor gliding overhead. Its massive wingspan and bright red head made it hard to miss.

“See, it’s here early!” my daughter announced.

What’s ‘wild’ when humans interfere?

This episode captured the complexity that journalist Emma Marris explores in “Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World,” a hard look at what it means for a species to be “wild” or “natural” on a planet where humans have radically altered it.

Condors were then and still are critically endangered: At the end of 2020 their wild free-flying population was 329, spread across parts of Arizona, Utah, California and Baja. The most dire threat they face is poisoning from consuming lead shot in animal carcasses they feed on.

And they’re present at the Grand Canyon because they were reintroduced there from a captive breeding program

We may value wild animals, but we interfere with their lives in all kinds of ways that call into question what “wild” means.

“The condors that have been released into the ‘wild’ are still tended to pretty closely by humans,” Marris writes. “They are routinely vaccinated against West Nile virus. When chicks are in the nest, they are visited monthly to make sure their parents aren’t feeding them plastic trash. If they are, the nestlings are whisked away for a quick surgery to remove the plastic. Every condor is assigned a ‘studbook number,’ which it wears prominently on a wing tag.”

Condors illustrate Marris’ central point: We may value wild animals and want to have good relationships with them, but we interfere with their lives in all kinds of ways that call into question what “wild” means.

Hybrid of wild nature and human management

Captive breeding programs are an example. Reintroductions, such as the planned return of gray wolves to Colorado that state voters endorsed in a 2020 ballot measure, are another. So is exterminating predators to protect at-risk species they hunt.

In one well-known example, the National Park Service killed thousands of feral pigs on California’s Channel Islands to save small endemic foxes. The program was so controversial that novelist T. Coraghessan Boyle novelized it in his 2011 book, “When the Killing’s Done.”

In her previous book, “Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World” (2013), Marris argued that the idea of preserving nature in a pristine, pre-human state was unrealistic, and that instead the goal should be a hybrid of wild nature and human management.

“Wild Souls” extends this line of thinking to wildlife, drawing on science, philosophy and literature for perspective.

Too often, Marris asserts, we divide the world into nature, which we view as good, and our domesticated world, which we blame ourselves for ruining. In her view, this either/or framing is too simple — and it also is harmful.

Acknowledging human influence

“Our concepts of ‘nature’ and ‘wilderness’ sadly limit the solutions that we can imagine,” she writes. “To make good environmental decisions, we must stop focusing on trying to remove or undo human influence. … We must instead acknowledge the extent to which we have influenced our current world and take some responsibility for its future trajectory.”

What does that mean in practice?

One example Marris raises is tolerating hybridization between some species — such as grizzlies and polar bears, or barred and spotted owls — if it expands the gene pool for a dwindling species.

Another might be deciding to let a hyper-specialized rare species go extinct, rather than inflicting mass suffering on its better-adapted predators.

A third is using genetic editing tools to help species that we want to protect adapt to a human-altered world.

“Imagine using a gene drive to remove horns from all rhinos so there would be no reason to poach them — and then using another gene drive 100 years later to put the horn back once the market has dried up,” she posits.

None of these interventions would be simple.

But with the Earth losing so many species now, “Wild Souls” is a heartfelt but practical guide through the tangled moral underbrush.

Jennifer Weeks is senior environment and energy editor at The Conversation US and a former board member of the Society of Environmental Journalists.