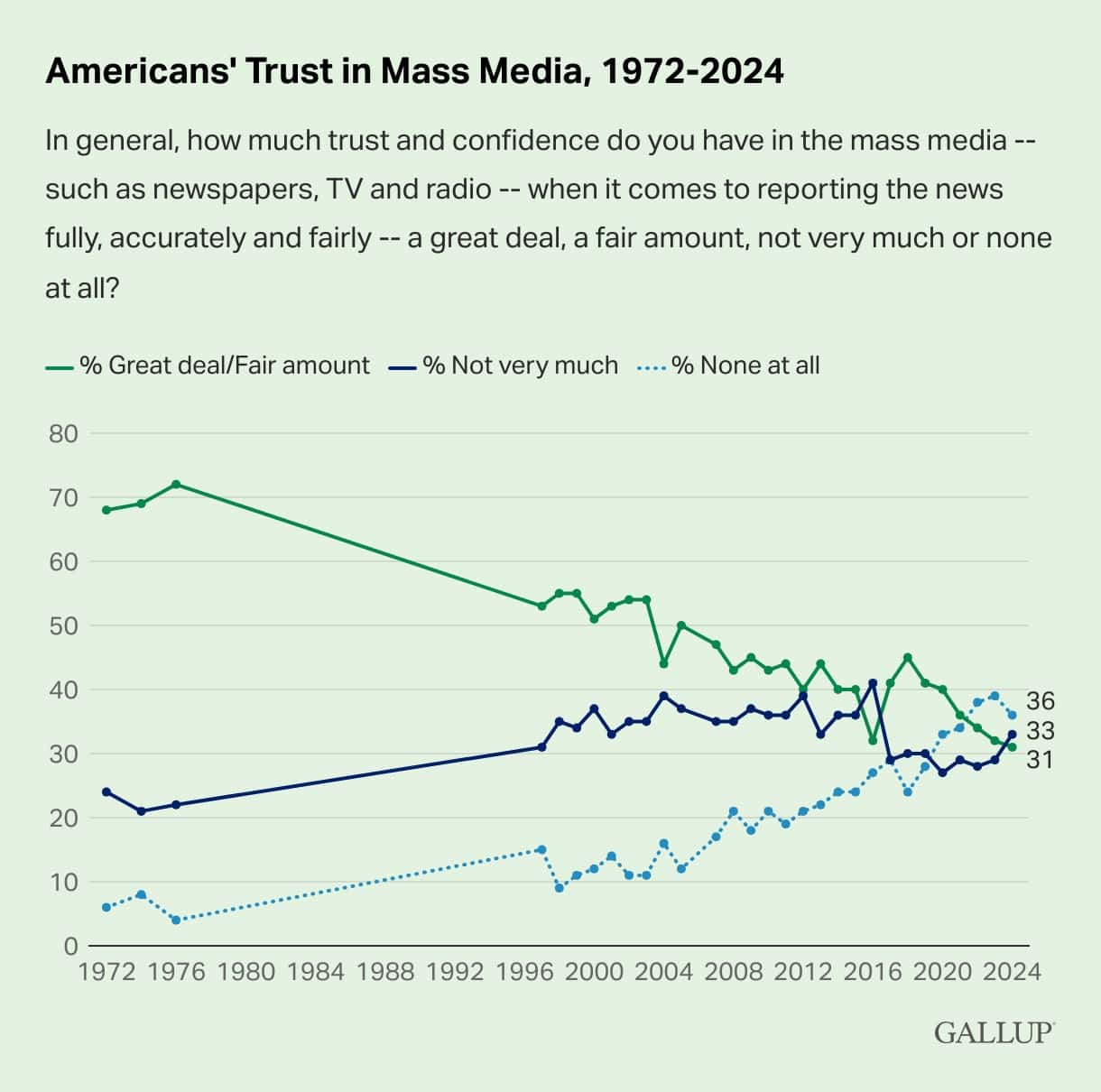

In case you aren’t following media news, there was a recent Gallup poll on confidence in various institutions. There was much wailing and gnashing of teeth in that sector.

The news media is the least trusted group among 10 U.S. civic and political institutions involved in the democratic process. The legislative branch of the federal government, consisting of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, is rated about as poorly as the media, with 34% trusting it.

In contrast, majorities of U.S. adults express at least a fair amount of trust in their local government to handle local problems (67%), their state government to address state problems (55%), and the American people as a whole when it comes to making judgments under our democratic system about the issues facing the country (54%).

But perhaps this is simply a transition, and more trustworthy sources of information will replace the media as we know it.

I see folks like The Hotshot Wakeup as a vanguard of a new and better media ecosystem. For one thing, he knows the territory, knows the people, and has been around for awhile. Trust is something that develops over time, when he turns out to be correct and when he acknowledges that he got it wrong. So it makes more sense to trust humans rather than institutions. We can trust District Ranger X and not “the Forest Service.”

So let’s look at some THW stories and how other media covered the same stories.

- Arrested burn boss.

MM (mainstream media) “remember Bundys” “employees will be afraid to conduct prescribed burns.”

THW “things got out of control, probably a one off.”

2. North Carolina FEMA threats

MM repeats rumor (?) of large group, focused on FS being called off.

THW reports in real time that FS folks were called back the next day, turned out to be one person threatening.

3. Oregon Department of Forestry

Apparently there were articles in the MSM about ODF. Three managers called THW to share their side of the story.

They also all agreed that this was a major distraction from the real issues with ODF right now. They are coming off a record wildfire season in Oregon and have major budgetary issues. Last month, they had to ask the state for emergency funds to continue funding the agency for a total of $42 million. Their employees just finished a rammer season, and the first week back in the office, they are all being bombarded with this story instead of focusing on close out, end of season duties, and decompression.

They saw this as an opportunity for media folks on both sides of the political aisle to use this story as ammo during a very contentious election cycle, and they were not very happy about that. Quite frankly, the timing couldn’t have been worse for the agency and their employees.

And that’s it. That’s the story from three managers inside ODF who feel like the agency they love and have spent their lives working for has been dragged into the mainstream media for political gain on both sides. So much so that they reached out and asked me to tell their story.

4. Bridger Aerospace

MM- Here’s a link to the Wall Street Journal op-ed on how political forces are trying to take down a fire aviation company,

Yet the closer Mr. Sheehy came to winning the nomination, the more hostile the environment became for Bridger. Late last year the company started getting strange inquiries from lenders and regulators—leading some managers to suspect that people were lodging accusations against it in hope of triggering lenders to pull loans or provoking a public regulatory rebuke.

After Bridger weathered that storm, the assault went public. In early August, NBC and the Washington Post ran negative articles a day apart making strikingly similar suggestions of a coming Bridger financial collapse, based in part on the anything-can-happen disclaimers that public companies are required to file. NBC also quoted Marc Cohodes—a short seller who has praised Sen. Elizabeth Warren as “great” and who routinely bashes Mr. Sheehy and Donald Trump—accusing Bridger of existing “for insiders and the Park Avenue billionaires at Blackstone.”

Mr. Cohodes, who owns a Montana home, then made public a letter he’d sent demanding the federal government probe Bridger over “false statements” on a federal form, and asking Gallatin County commissioners to investigate Bridger’s use of local bonds it received. The letter was signed by seven other Montana businesspeople, most donors to Democrats and to Mr. Tester. “The bottom line is [Bridger’s] going to go broke,” Mr. Cohodes told a Montana outlet.

The negative headlines mostly failed to explain that a Bridger employee had accidentally ticked the “SDB” (socially disadvantaged business) box, instead of the “SDVOSB” (service-disabled veteran-owned business) box on a federal form that tracks demographics. Or that the Gallatin Commission issued a statement that it had received a “politically motivated” inquiry that seemed to “stem from a misunderstanding of conduit private activity bonds.

********************

The Tester campaign has amplified the attacks and has an ad claiming the company is “failing.” This is appalling, given the attacks are a huge hit on employees, some of whom are veterans and all of whom were issued stock. Local residents who invested in a hometown company have also been harmed.

Planes are capital-intensive and Bridger does have debt; it’s also growing and has posted record revenue and contract awards. Bridger Chairman Jeffrey Kelter says in an interview that Bridger “is a Montana company with 200 employees and a mission to protect lives and property, whose growth trajectory has been consistently great.” He points to a board of directors with heavy hitters from banking and investment, and notes this has been a “very, very good year for Bridger.” After decades in executive roles, he finds “for a small company to get this level of negative attention is unprecedented.”

Mr. Sheehy stepped away from Bridger in July to minimize any conflicts and focus on his campaign. But he’s unhappy that Bridger employees are bearing the fallout of these attacks. “Certain things should be out of bounds in politics,” he says, “A sitting senator trying to destroy a business in the state he is supposed to represent is one of them.”

THW reached out to both sides, Sheehy spoke to him and none of the many Tester offices answered his requests for comments.

I totally understand the political angle, and that Montana is important for the whole country because of the Senate and so on. I guess political entities have bought into the idea that “the ends justify the means”. If we circle back to the media, it means that we basically can’t trust them to achieve escape velocity from any politically convenient narrative.

***********

As THW shows, it’s not really that difficult to listen to both sides, be even-handed and let the chips (so to speak) fall where they may. It may be a tough business model, though, as in our world there are many foundations and not-for-profits seeding MSM with stories that support their worldview.

And yet, reporters’ knowledge and experience over time can provide essential context for our understanding, plus are closer to people on the ground observing situations in real time. Bottom line: I see a much more vibrant, diverse and trustworthy news ecosystem struggling to be born.