The Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest has completed revising its forest plan. The final plan was released on February 16 and implementation began last week. The revision website is here, and the response to the objections is here.

Said Sam Evans, leader of the National Forests and Parks Program for the Southern Environmental Law Center (and Smokey Wire contributor) “A big disappointment for me here at the end of the process is that it is more of the same. It’s going to drive a wedge between stakeholders that had found consensus.” “We can sue over the plan,” Evans said. “We can oppose projects as they come up under the new plan. I would say the only thing that’s not an option for us is letting this plan roll out and be implemented in a way that continues to degrade those same resources — unroaded areas, healthy, intact forests like the state Natural Heritage Areas and existing old growth.” The ”stakeholders” would be the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Partnership of 20 interested organizations. This article continues to discuss these disappointments in more detail (though apparently not all of the stakeholders are unhappy).

The Partnership wanted to see various tier objectives tied together so that, for instance, the Forest Service couldn’t move on to Tier 2 timber harvest goals without first meeting Tier 1 goals in other areas, such as invasive species management and watershed protection. Additionally, the Partnership said, the plan should require ecological restoration treatments to be paired with any commercial timber harvest occurring on the forest landscape.

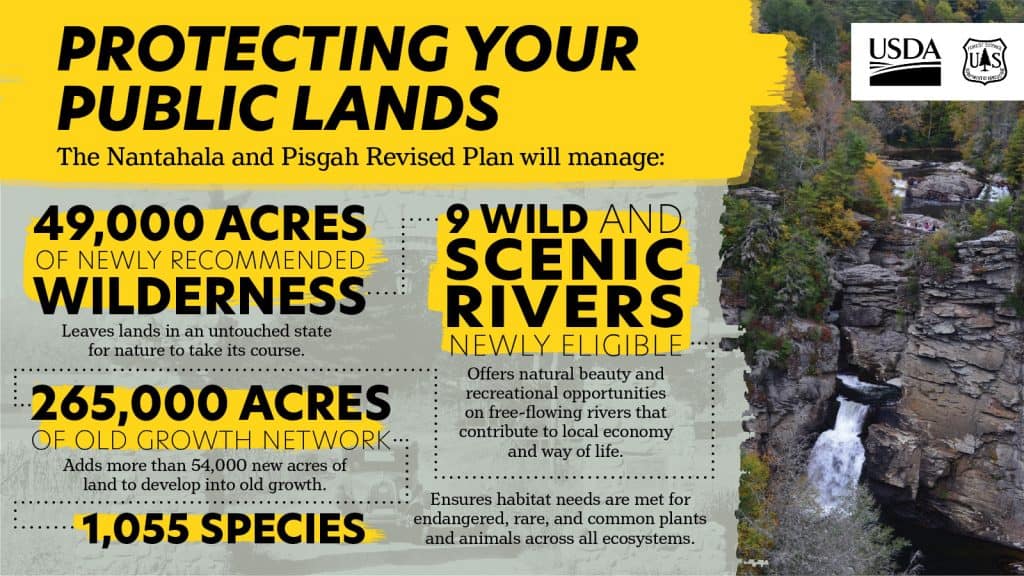

The group was also concerned that 54,000 acres of state Natural Heritage Natural Areas were placed in management areas open to commercial logging and road building, and that the plan didn’t allow for protection of old growth patches found during timber projects. The group wanted to see a “cap and trade” approach to the 265,000-acre Old Growth Network identified in the plan, so that lower-quality patches in the network could be swapped out for higher-quality patches encountered during projects.

According to Evans, only 30,000 acres of the 265,000 acres is at the minimum age level to qualify as old growth, and the remainder is middle-aged forest of 60-100 years. Meanwhile, known old growth stands were not included in the network. The Forest Service does not have a figure for the number of acres in the network that currently qualify as old growth. “We’re trading young forest that maybe will become older one day for existing old growth now,” Evans said, “and that isn’t a good trade for the species that live in old growth forests and don’t move around.”

The forest supervisor had an interesting response to this old growth issue: “Because of the complexity of the forest, there’s always going to be places that we might find a particular stand that is in that older forest type, and we can say, ‘You know what, that’s an area that’s special, and that we want to favor for those types, and that’s part of a larger project that’s holistic in a given area,’” he said. They CAN say that project-by-project, but by allowing that flexibility, does the PLAN comply with the requirements for it to affirmatively provide habitat for at-risk species?

There is also disagreement about whether it does what it should to address climate change. It apparently pits carbon storage (mitigation) vs “resilience” (adaptation). Shouldn’t carbon storage projections include any additional risk of having less “resilient” forests? There was a recent question on this blog about how forest plans are dealing with climate change. This article (which also highlights the criticisms of the plan) lists the Forest Service’s seven main goals for “dealing with the impacts of climate change” (which are about adaptation rather than mitigation)

- “Where there are species at risk that are susceptible to the effects of climate change, promote activities that support suitable habitat enhancement.

- “Consider and address future climate and potential species range shifts when planning restoration projects, facilitating species migration and adaptation when possible.

- “Monitor for new invasive species moving into areas where they were traditionally not found, especially in high-elevation communities. Utilize the monitoring information to assess threats and prioritize treating highly invasive infestations.

- “Restore native vegetation in streamside zones to help moderate changes in water temperature and stream flow and enhance habitat.

- “Anticipate and plan for changes in natural disturbance patterns.

- “Prepare for intense storms and fluctuations in base flow using methods that maintain forest health and diversity, including controlling soil erosion, relocating high risk roads and trails, and constructing appropriately sized culverts and stream crossings while retaining stream connectivity.

- “To maintain genetic resiliency, consider locally adapted genotypes for use in restoration projects.”

What’s next? Will Harlan, a scientist for the Center for Biological Diversity said (here) communities still not satisfied with the decision will “use every tool possible” including “public engagement, community involvement (and) litigation” to push back against what the plan could do to forests.

However, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians was “pleased.”