I am going to go out on a limb here..I think the way some groups in tight with the Admin, or possibly the Admin itself (can’t easily tell), have chosen to classify federal lands for “counting” in 30 x 30 is messed up and potentially meaningless. To get started, I think it’s important to define terms. I’m going to capitalize Protection when I mean “protected areas as defined by various entities, that is, GAP 1 and 2, for the 30×30 effort.” In the next post, we’ll look at what’s in and what’s out based on the recent Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni — Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument (BNIK NM) declaration. It seems to me mostly like BAU for the BLM and FS, but requiring another planning process :(. I’m not sure that most of the reporters read the declaration itself and not just the press release.

The Center for American Progress (CAP) is a very powerful political entity and here are their policy recommendations.. it sounds like a laundry list of what the Biden Admin has been doing recently.

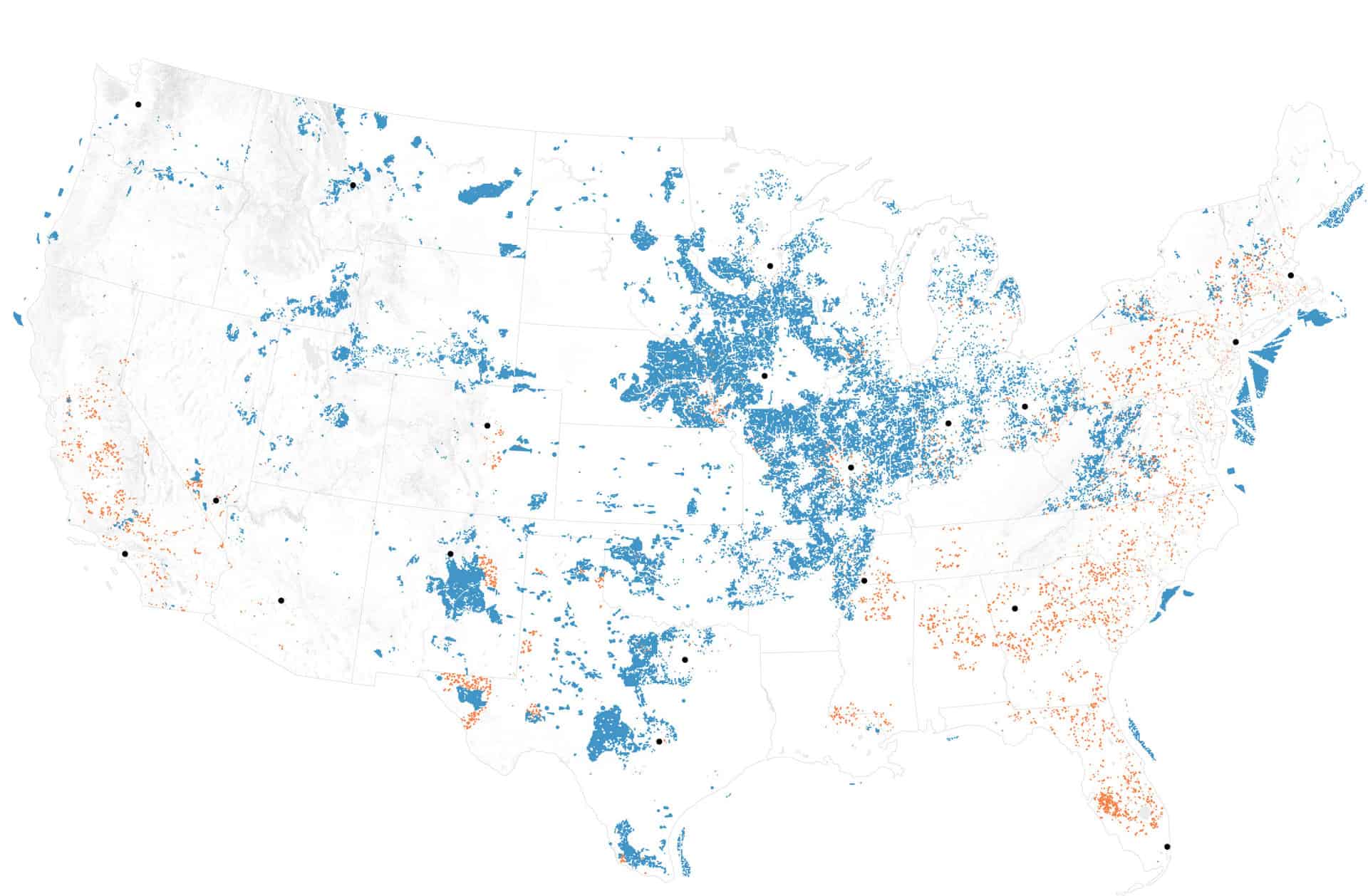

In a November 2022 report from its series on executive action to address the nature crisis, CAP took a deeper look at some of the most powerful conservation tools available to President Biden. In particular, the report identifies the top eight most impactful opportunities for near-term executive action. These include opportunities to designate new protected areas; expand national wildlife refuges; exclude sensitive and sacred places from drilling and mining; and establish national rules to guide conservation of U.S. Bureau of Management lands and the country’s oldest federally owned forests. In another publication from the same series, CAP highlights specific community and Tribally-led proposals for national monuments and marine sanctuaries already primed for executive action, from the proposed Avi Kwa Ame National Monument in Nevada to the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary in California. Enacting these recommendations will deliver real conservation benefits and should be prioritized.

They also indicated that to them, talking about “what counts” is beside the point.

However, heated arguments about “what counts” can miss the much bigger point behind this national “30×30” conservation goal. The ambitious 30×30 target can, and really must, be an inclusive call to action—a promise to jointly address the climate and biodiversity crises by accelerating the pace at which the country is protecting nature.

As a scientist, I see two problems with CAP’s formulation. First, if you are indeed thinking about climate and biodiversity, then to make progress you would absolutely need to define what you want specifically, and various risks, and identify tradeoffs. Second is that, of course, just Protecting something does not actually address both climate and biodiversity. Not a burned tree nor a cheatgrass seed cares much about lines on maps (back to the BLM sage grouse habitat paper).

A simple example is this Oregon Public Broadcasting story about the Bootleg Fire and carbon credits (which is a good article to read anyway). If you take out the cap’n’trade carbon credits part of the story, you have “adios, carbon we thought we had” from the area. You can say that somehow this wouldn’t have happened if it had been in a Protected area, or somehow wouldn’t have had negative effects on biodiversity and carbon simply by drawing a line! How cool is that? But not actually real in terms of biology.

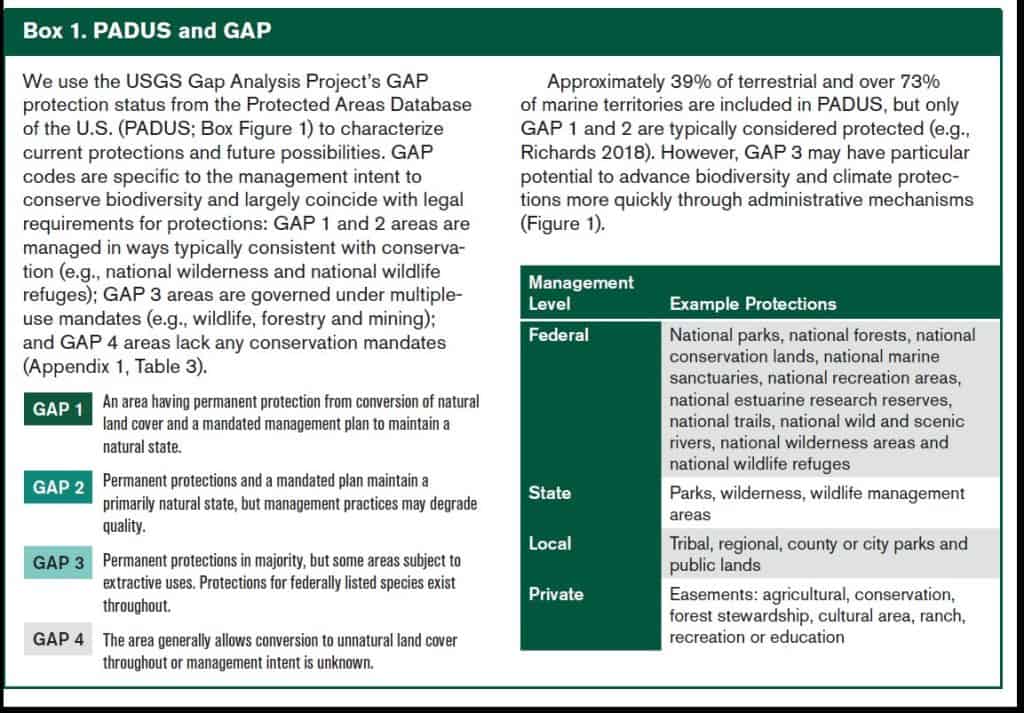

So the question that CAP raised is actually pretty important.. what’s in and out for 30 x 30? Defenders of Wildlife, for example, and the State of California, think it should only include Gap 1 and 2 acres.

*************

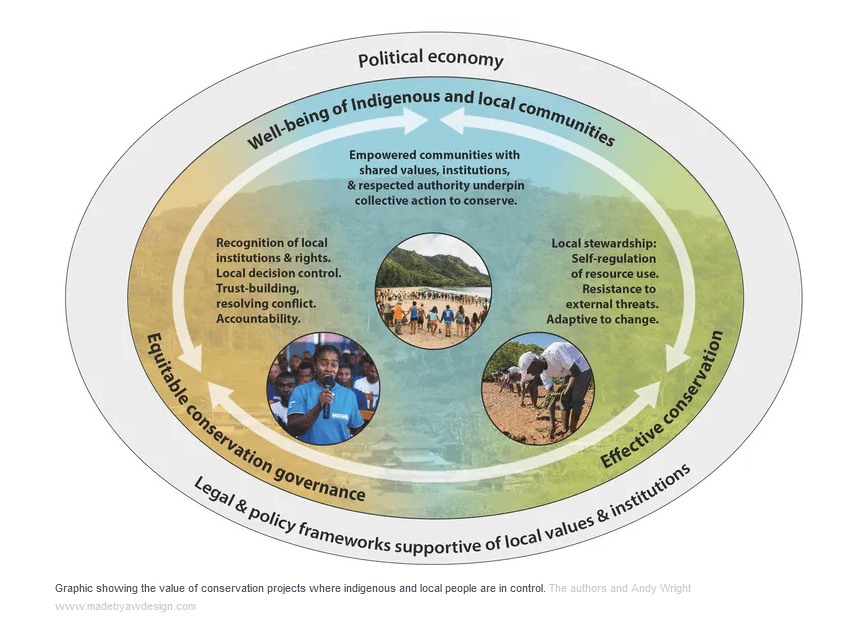

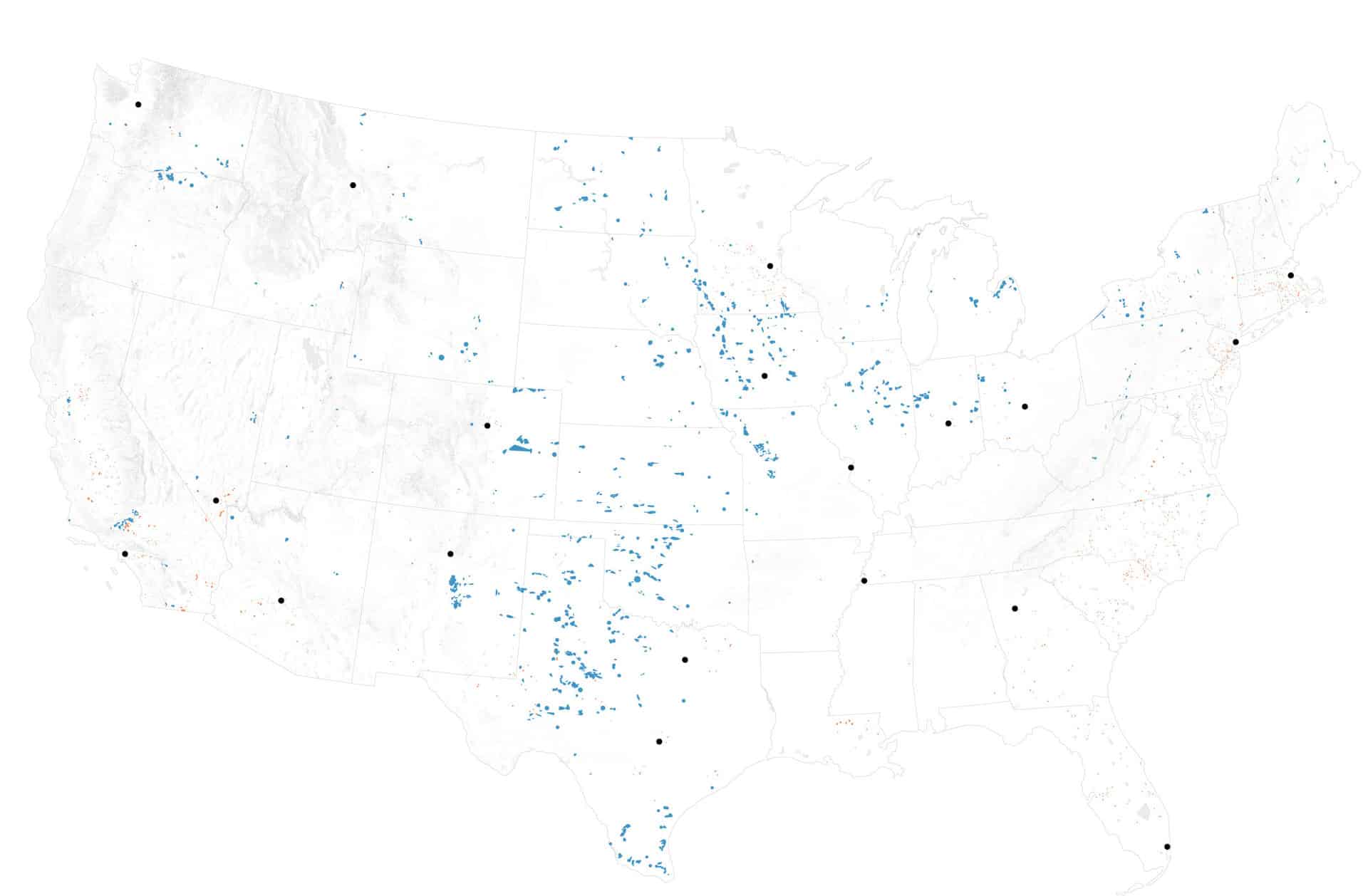

I couldn’t find a place where the Biden Admin says what counts to them toward 30 x 30. I did find that CEQ, Interior, USDA and Commerce wrote an interesting paper on how to achieve 30 x30 that leads with “Pursue a collaborative and inclusive approach to conservation” (see table of contents above). There were also statements by the Admin about how working lands should count.

The interesting thing about using Gap 1 and 2, as per Defenders and others, is that, say Forest Service Roadless Areas are not included, as they are not “permanent,” but places like the San Gabriel National Monument are included as Protected. Having worked for years on Roadless, they seem pretty permanent to me. I’m sure if you tried to measure “intactness” they would beat the SG National Monument or even parts of Yellowstone (Gap 1) by a mile. It seems like a serious general flaw that these definitions consider recreation-even industrial scale- as no barrier to Protection. And in GAP1 all you need is a “management plan” to maintain a natural state.. not actually a.. “natural state” whatever that is.

Which as far as I’m concerned from any biological point of view, is pretty meaningless. So let’s move on to the new National Monument.

Here’s a link to the Monument Proclamation- now remember that all these acres were managed by BLM and the Forest Service under their multiple- use mandate. But GAP- wise, just the President’s signature on a piece of paper transforms them into Protected.

There’s lots of verbiage about how declaring the area a Monument will “address the legacy of dispossession and exclusion” but the actual actions in the Monument sound like BLM and FS current policy.

Conserving lands that stretch beyond Grand Canyon National Park through an abiding partnership between the United States and the region’s Tribal Nations will ensure that current and future generations can learn from and experience the compelling and abundant historic and scientific objects found there, and will also serve as an important next step in understanding and addressing past injustices.

Then they make the case for historic and scientific significance that they need to make for the Antiquities Act and to argue that 1.1 mill acres is the least amount of acres necessary I do see this as heading to the Supreme Court if some people with lawyers care enough.

If you read through the paragraphs, it sounds like the BLM and the FS have been doing a swell job. You could also get the impression that almost any area could equally qualify with historic habitation by Native people, early Euro-American history, biodiversity and scientific interest. Here’s an example:

Protecting the areas to the northeast, northwest, and south of the Grand Canyon will preserve an important spiritual, cultural, prehistoric, and historic legacy; maintain a diverse array of natural and scientific resources; and help ensure that the prehistoric, historic, and scientific value of the areas endures for the benefit of all Americans. As described above, the areas contain numerous objects of historic and scientific interest, and they provide exceptional outdoor recreational opportunities, including hiking, hunting, fishing, biking, horseback riding, backpacking, scenic driving, and wildlife-viewing, all of which are important to the travel- and tourism-based economy of the region.

Yup, sounds like the point is to keep protecting what the BLM and FS already protected..

Next post: let’s see what is going to continue, and what will change, at BNIK NM.