We’ve looked at two scientific papers in the last week, last Friday Siirila-Woodburn et al. “low to no snow future and water resources” as we discussed here. Then yesterday we took a look at Ager et al. 2021. as part of a discussion about the Forest Service 10 year wildfire risk reduction plan. Today I’d like to look at a recent paper by Law et al. that Steve brought up in a comment yesterday. It’s interesting for many reasons, not the least of which is that the journal, Communications Earth and Environment publishes the review comments and responses, and is open access. Apologies for the length of this post, but there’s lots of interesting stuff around this paper.

The first question is “what is the point of the paper?” In the discussion, the authors say

“We developed and applied a geospatial framework to explicitly identify forestlands that could be strategically preserved to help meet these targets. We propose that Strategic Forest Reserves could be established on federal and state public lands where much of the high priority forests occur, while private entities and tribal nations could be incentivized to preserve other high priority forests. We further find that preserving high priority forests would help protect (1) ecosystem carbon stocks and accumulation for climate mitigation, (2) animal and tree species’ habitat to stem further biodiversity loss, and (3) surface drinking water for water security. Progress has been made, but much work needs to be done to reach the 30 × 30 or 50 × 50 targets in the western US.”

Basically, to put words in their mouths, they used geospatial data from various sources to help figure out how to meet 30×30 and 50×50 goals. It seems to me that they equate “preervation” to “conditions that are good for carbon stocks, biodiversity, and drinking water.” This is perhaps fine in a non-fire environment (and we can all make assumptions about future fires on the West Side, but if we were perfectly honest we’d admit that “fires may well occur on the west side as well and possibly increase” but “no one knows for sure.”

Now if we were to raise our sights from the details of the geospatial framework, we might see that 30 x 30 is a current policy discussion about how much conservation versus protection and what practices count. So they might have taken the same tack as Siirila-Woodburn and Ager’s coauthors.. “let’s ask the people who know about these practices and are working in the area what they would like to know that would help them. Keeping in mind that these systems are so complex, we can’t really predict and need to be open about uncertainties.” There’s also a substantial literature about these national or international priority setting analyses, and their tendencies to disempower local people. No reviewers of this paper that I could tell were social scientists.

Nevertheless, it seems like they ran some numbers, and then had a long discussion in a mode of an op-ed with citations.

Differences in fire regimes among ecoregions are important parts of the decision-making process. For example, forests in parts of Montana and Idaho are projected to be highly vulnerable to future wildfire but not drought, thus fire-adapted forests climatically buffered from drought may be good candidates for preservation. Moist carbon rich forests in the Pacific Coast Range and West Cascades ecoregions are projected to be the least vulnerable to either drought or fire in the future25, though extreme hot, dry, and windy conditions led to fires in the West Cascades in 2020. It is important to recognize that forest thinning to reduce fire risk has a low probability of success in the western US73, results in greater carbon losses than fire itself, and is generally not needed in moist forests79,80,81,82.

Biodiversity- wise, though, you don’t need a PhD in wildife ecology to think.. protecting more west-side Doug-fir isn’t as good for biodiversity as protecting some of that and some of Montana or New Mexico.. so really carbon and biodiversity don’t always lead us to the same places. It’s interesting that the reviewers didn’t catch the claim that “forest thinning has a low probability of success” What is paper 73, you might ask? It’s a perspective piece in PNAS (so another op-ed with citations) by our geography friends at University of Colorado. And “results in greater losses than fire itself?” See our California versus Oregon wildfire carbon post here.

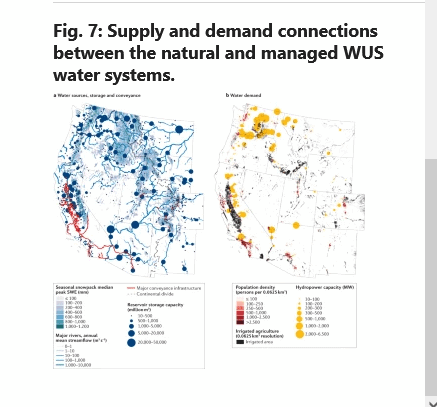

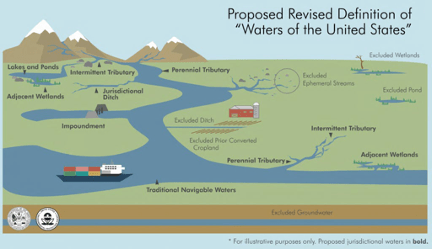

Forests help ensure surface drinking water quality63,64 and thus meeting the preservation targets would provide co-benefits for water security in an era of growing need.

This was an interesting claim for “protected” forests, as our hydrology colleagues (who perhaps are more expert in this area?) wrote in their review..

Changes in wildfire frequency, severity and timing are particularly catastrophic consequences of a low- to- no snow future. Indeed, alongside continued warming, a shift towards a no- snow future is anticipated to exacerbate wildfire activity, as observed169,170. However, in the longer term, drier conditions can also slow post- fire vegetation regrowth, even reducing fire size and severity by reducing fuels. The hydrologic (and broader) impacts of fire are substantial, and include: shifts in snowpack accumulation, snowpack ablation and snowmelt timing171; increased probability of flash flooding and debris flows172,173; enhanced overland flow; deleterious impacts on water quality 174,175; and increased sediment fluxes176,177. Notably, even small increases in turbidity can directly impact water supply infrastructure178,179. Vegetation recovery within the first few years following fire rapidly diminishes these effects, but some longer term effects do occur, as evidenced with stream chemistry180 and above and below ground water partitioning both within and outside of burn scars181.

There’s even a drive-by (so to speak) on our OHV friends..

Recreation can be compatible with permanent protection so long as it does not include use of off-highway vehicles that have done considerable damage to ecosystems, fragmented habitat, and severely impacted animals including threatened and endangered species37

Here’s a link to the review comments. The authors did not include fragmentation in their analysis as one reviewer pointed out, so they added

Nevertheless, our current analysis did not incorporate metrics of forest connectivity39 or fragmentation48, thus isolated forest “patches” (i.e., one or several gird cells) were not ranked lower for preservation priority than forests that were part of large continuous corridors.

To circle back to handling uncertainty and where the discussion of these uncertainties takes place (with practitioners and inhabitants or not), another review comment on uncertainty and the reply:

The underlying datasets that we used in this analysis did not include uncertainty estimates and thus it is not readily possible for us to characterize cumulative uncertainty by propagating uncertainty and error through our analysis. We recognize the importance of characterizing uncertainty in geospatial analyses and acknowledge this is an inherent limitation in our current study. To better acknowledge this limitation and the need for future refinements, we added the following text to the end of the Discussion (lines 445-447): Next steps are to apply this framework across countries, include non-forest ecosystems, and account for how preservation prioritization is affected by uncertainty in underlying geospatial datasets.

It makes me hanker for old timey economists, who put uncertainties front and center. Remember sensitivity analysis?

But the reviewers never addressed the gaps that I perceive between what the authors claim in their discussion and what the data show. I suspect that’s because “generating studies using geospatial data” is a subfield, and the reviewers are experts in that, but the points in the discussion (what’s an IRA, what’s the state of the art on fuel treatments) not so much. I think that that’s an inevitable part of peer review being hard unpaid work- at some point reviewers will use the “sounds plausible from here” criterion. And so it goes..