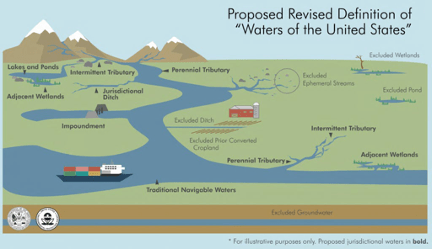

Not long ago we were discussing EPA’s new regulations redefining WOTUS to exclude areas that were not obviously connected to navigable waters, as summarized in the graphic above. It was the latest iteration of a political dispute over the scope of the Clean Water Act. Now the U. S. Supreme Court has, in a 6-3 decision, stepped in to apparently invalidate the recent “bright line” rule established by the EPA to again make point source permit requirements contingent on the actual risk of pollutants getting into navigable waters. This somewhat splits the difference between the Obama and Trump interpretations, but clearly rejects the latter’s new absolute position. “Significant nexus” has now become “functional equivalent.”

On April 23, 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the addition of pollutants to groundwater which travels a half mile to enter navigable waters is the functional equivalent of a direct discharge, and subject to the protections and requirements of the Clean Water Act (“CWA”). The decision in County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, 590 U.S. (2020), represents a sea change in CWA interpretation, and may spell the end of the Navigable Waters Protection Rule issued by EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers only two days earlier. That rule (colloquially known as the 2020 WOTUS Rule) specifically excluded groundwater from the protections of the CWA under a new definition of “Waters of the United States.”

In determining that the CWA requires a permit when there is a functional equivalent of a direct discharge from a point source to navigable waters, the Supreme Court acknowledged that application of the statute will be highly fact dependent, with time and distance being critical issues in most cases.

In addition, a federal district court has stopped the Keystone Pipeline because its Clean Water Act permit for stream crossings is invalid. This is significant because the permit was kind of the Clean Water Act equivalent of a NEPA categorical exclusion, a nation-wide blanket permit requiring limited environmental review that could be used for certain kinds of projects. The court said that when the permit was renewed in 2017, the Army Corps of Engineers failed to adequately consider effects on species listed under the Endangered Species Act. Since then the permit has been used 37,000 times. So here’s what’s happening ….

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has suspended a nationwide program used to approve oil and gas pipelines, power lines and other utility work, spurred by a court ruling that industry representatives warn could slow or halt numerous infrastructure projects over environmental concerns.

The Trump administration is expected to challenge the ruling in coming days. For now, officials have put on hold about 360 pending notifications to entities approving their use of the permit, Army Corps spokesman Doug Garman said Thursday.

Pipeline and electric utility industry representatives said the effects could be widespread if the suspension lasts, affecting both construction and maintenance on potentially thousands of projects. That includes major pipelines like TC Energy’s Keystone XL crude oil line from Canada to the U.S. Midwest, the Mountain Valley natural gas pipeline in Virginia and power lines from wind turbines and generating stations in many parts of the U.S.

The Forest Service is involved with litigation of the Mountain Valley Pipeline as discussed most recently here.

Jon, can you explain how the Court decided that 1/2 mile was the critical number? Not 1/4 not 3/4..??

“Highly fact dependent” sounds like a full employment program for attorneys.. no wonder people like farmers (who may not have money to pay attorneys) are concerned.

1/2 mile was the distance in this case. Here’s what the Court said about future cases:

“Time and distance are obviously important. Where a pipe ends a few feet from navigable waters and the pipe emits pollutants that travel those few feet through groundwater (or over the beach), the permitting requirement clearly applies. If the pipe ends 50 miles from navigable waters and the pipe emits pollutants that travel with groundwater, mix with much other material, and end up in navigable waters only many years later, the permitting requirements likely do not apply.”

I would say it’s a full employment program for hydrologists, but I agree it leaves a legal question of how far and fast is within the scope of the law. I agree that this structure does not make it easy for permittees, but it is what the Supreme Court says it is. (If legislation is the answer, I could see a compromise featuring a relatively expansive interpretation that includes more specific criteria that make application easier.)