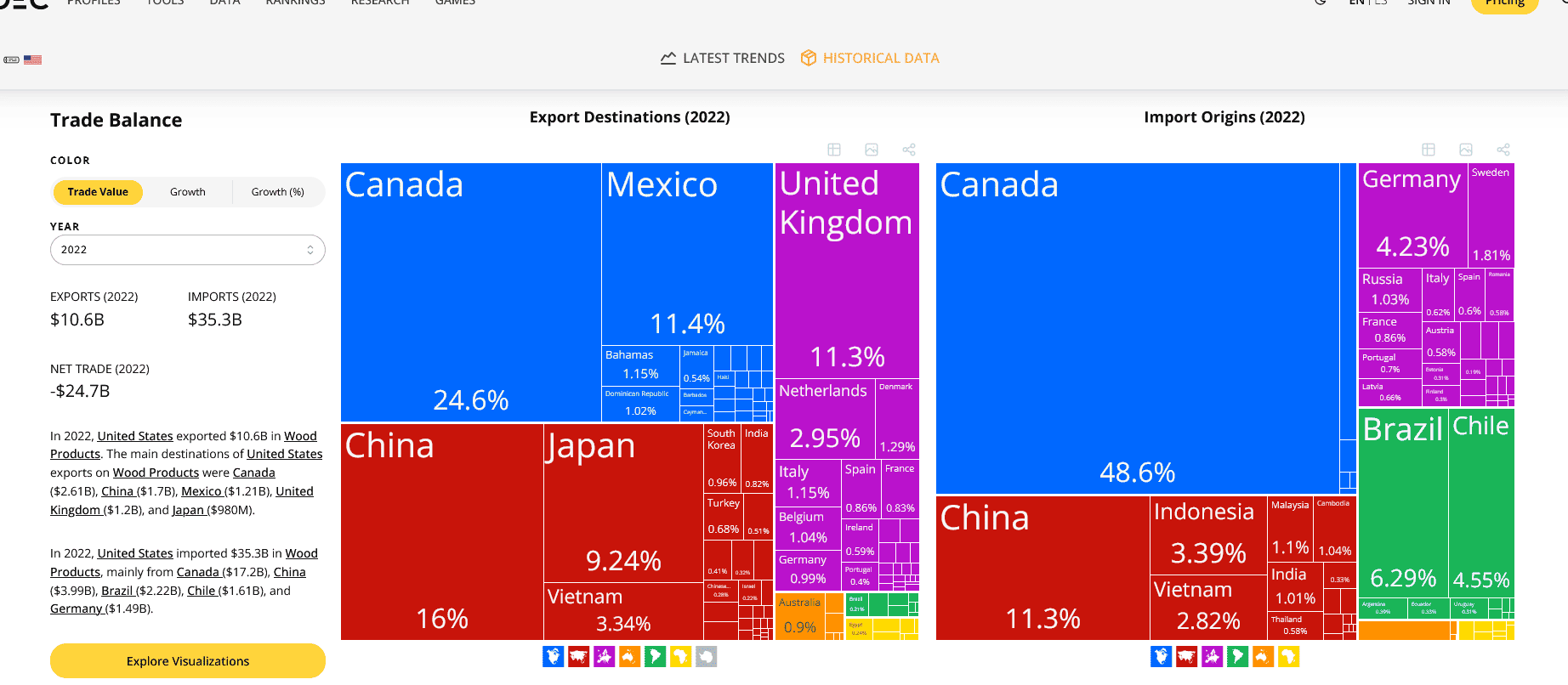

There were many interesting things to explore with the hearing on the Westerman Bill yesterday. As we saw in previous posts, it’s a compendium of many different ideas we can explore in greater depth. What I thought was one theme in Chris French’s testimony was what we might call another Wood Wide Web (broader than the mycological one discussed here a few weeks ago), this one of people, workers and organizations making useful products of wood.

Certainly mycorrhizal fungi help trees. But also people help trees, at least around here, by thinning them and protecting them from fires, planting them and so on. And trees provide us with useful products, often more environmentally friendly than those produced from minerals of various kinds. So, in fact, we as humans have some mutualism going on here with trees. And within that mutualism, we have a complex interrelationship of businesses and workers (from sawmills to CLT to paneling to furniture to horse bedding to sawdust to biochar to bioenergy) that depend on each other. And people who depend on the products they produce, plus employment, plus taxes. So indeed people have their own Wood Wide Web, and while Chris didn’t talk about it in those words, he made the point that this Web is important to forests surviving and thriving into the future, come climate change, wildfires and a variety of other stressors. Or at least that’s how I heard it. We are, indeed, all in this together.

********************************************

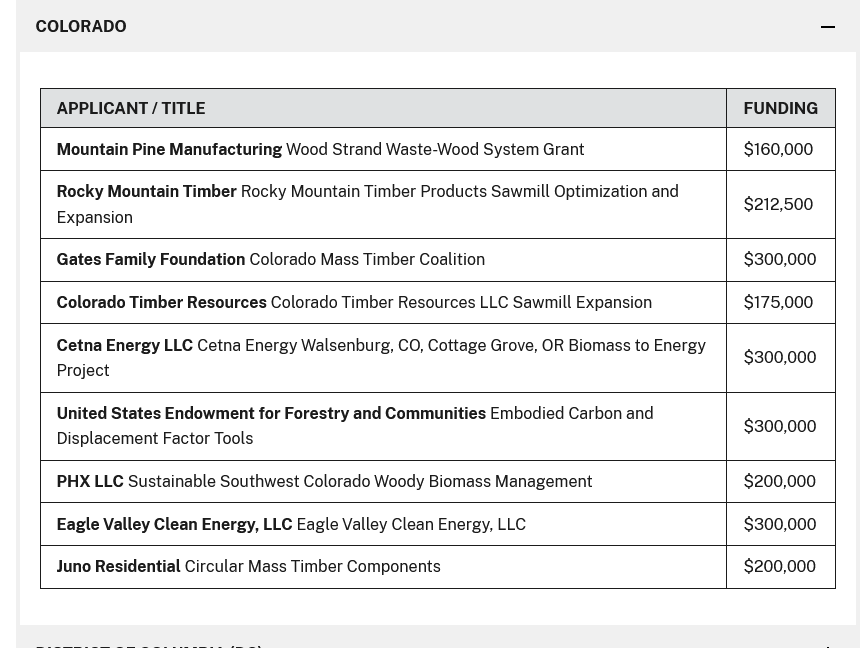

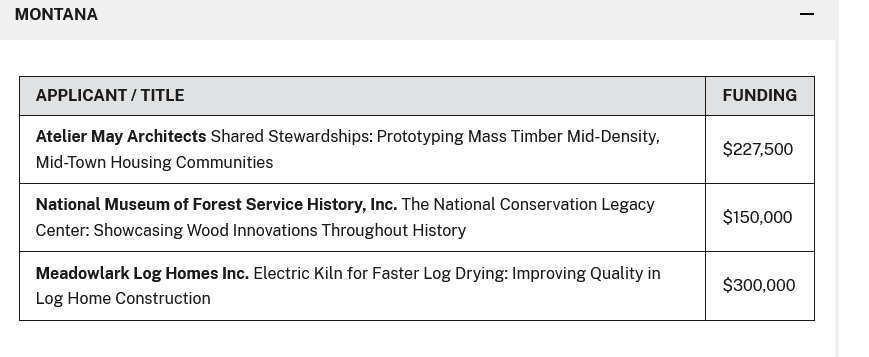

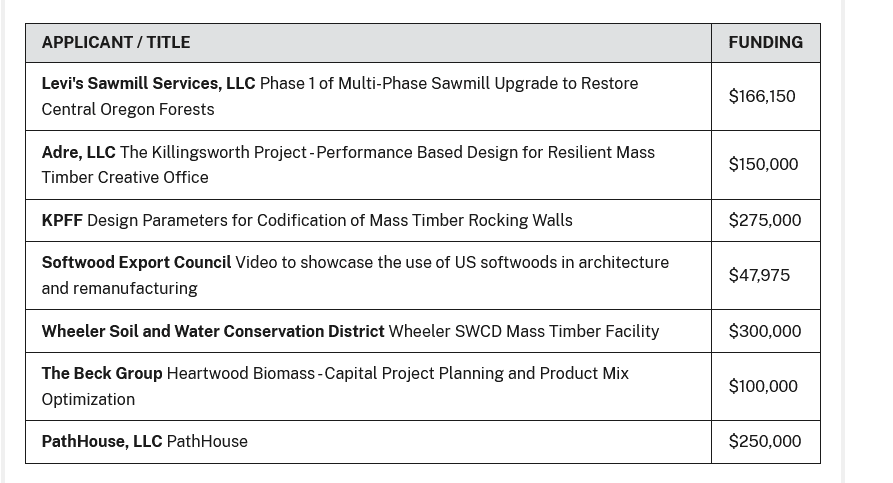

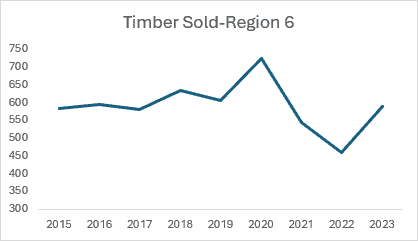

Housing is a crisis in many places in the US. And the US is allowing large numbers of migrants in (at least 2.5 million according to NPR) (not judging, just observing). It seems logical that we would need even more housing. Housing tends to be built using wood for various reasons, including cost. We have lots of extra wood from fuel treatment and restoration projects, but it tends to be small. Will new materials like CLT help us build our way out of the housing crisis? Certainly if we look at the Wood Utilization grants of USDA, there is much effort (and funding) going toward Mass Timber, CLT and other efforts. Maybe the future is small, local mills, with local employees scattered through the landscape. Which is kind of what we had, previously, except in the past they focused on larger dimension lumber.

I’m not a fan of top-down industrial policy, but if the wildfire folks can have a Cohesive Strategy, I don’t see why, given the massive amounts of biomass to be otherwise burned, we can’t have a Coherent (and what the heck, let’s throw in Cohesive also) Strategy.

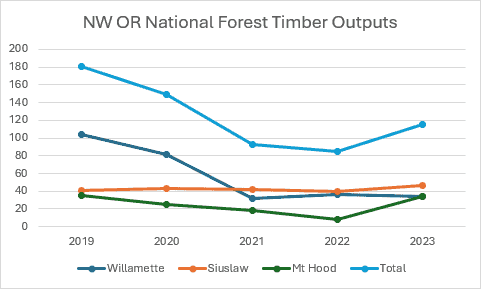

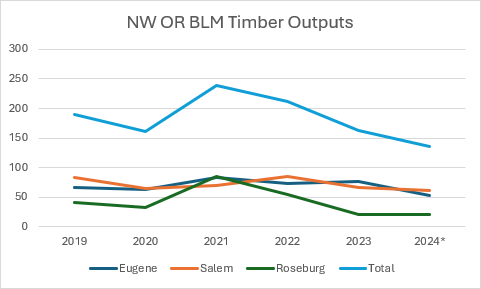

Current Dimensions Used (from AFRC)

I was curious about the size of material being used by current timber industry (including CLT mills). I know there are university and Forest Service experts out there, so hopefully they will add information here or you all can add good contacts.

AFRC generously provided me with their perspective on dimensions:

Log utilization is an ongoing point of contention between the federal agencies and AFRC. The Forest Service in Region 6 generally classifies minimum specifications for sawtimber as an 8-foot log with a small-end diameter of 5-6 inches for most conifer species. The only exception is ponderosa pine where they use a 16-foot log. AFRC has been advocating that the Forest Service use a 16-foot log for all conifer species for several years since most all of our members assert that 8-foot logs with 5-6 inch diameters do not get processed as saw material, but rather end up as pulp or chip material. Most of our members whose mills are designed to utilize small logs are capable of sawing or peeling down to 5-6 inches, but some minor variations exist. However, when delivered as an 8-foot piece, the economics of doing so becomes marginal—hence our advocacy to change that length.

The CLT facilities that I’m familiar with (Freres in Lyons and DR Johnson in Riddle) do not actually process raw logs—instead they secure veneer that has previously been peeled or boards that have previously been cut at other mills and then manufacture them into larger products by gluing them together. Generally speaking though, the products that are delivered to CLT facilities can be cut/peeled from small, medium, or large logs.

From loggers to end users – all of whom are currently involved in a complex exchange of material and value. Fiddling with a part may cause a series of consequences throughout the web. And 16 foot logs with 5-6 inch diameters are pretty small. With, no doubt, transportation costs being a big thing. Again, the web. Again, the need for a Double C (cohesive and coherent) strategy.

Academic Horsepower and Successful Industry-Chicken or Egg?

If your state has a prominent forest industry, generally (but not always) universities hire experts to help them, and conceivably the rest of us who use wood or want to get rid of biomass. But if your state doesn’t, then they probably don’t have experts. Which could be a problem if you want to support new industries, in that there are no/few experts to help entrepreneurs.

As I was writing the above on transportation costs, I received an announcement of a webinar by Drs. McConnell and Tanger who seem to be forest economics/wood utilization/operations experts.

Wood-using sawmills prioritize availability of raw materials, their accessibility, and associated transportation costs as the main drivers of new mill constructions and financial viability of existing mill operations. One of the major hurdles faced by the forest sector is hauling costs. Hauling costs have commonly been cited as comprising 35 to 45% of the delivered cost of round wood. Join us to learn how road network repairs could benefit both the forest sector and the broader Mississippi economy.

California’s Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force Market Development Program

I don’t know how many economics and utilization professors California has (I know there’s some in Extension) but they have a market development program that’s interesting. They have five pilot programs:

to establish reliable access to forest biomass through a variety of feedstock aggregation mechanisms and organizational innovations. The pilots will develop plans to improve feedstock supply chain logistics within each target region through the deployment of a special district with the authority and resources to aggregate biomass and facilitate long-term feedstock contracts. Each pilot will assess market conditions, evaluate infrastructure needs, and work to enhance economic opportunities for biomass businesses in their project regions. The pilots are distributed across 17 counties in the Central Sierra, Lake Tahoe Basin, Northeast California, North Coast and Marin County.

Their rationale is:

Diverting forest residues for productive use can help increase the pace and scale of forest restoration efforts in California, reducing vulnerability to wildfire, supporting rural economic development, and promoting carbon storage. The Wildfire and Forest Resilience Action Plan identifies the development of, and access to, markets for these residues as a key barrier to conducting necessary treatment activities across priority landscapes in the state. The development of such a market for residues has been hampered by the lack of any centralized broker capable of entering into long-term feedstock supply contracts.

Washoe Sawmill Opens

I posted about this last year, The Tahoe Fund, Tahoe Forest Products LLC, and the Washoe Development Corporation worked together to build a new mill. Here’s a link to a Bloomberg story. Region 5 has a good story about it opening, with some interviews and a historical perspective. Shout out to writer Andrew Avitt!

“The truth is, the forest, it needs our help,” said Serrell Smokey, Tribal chairman for the Washoe Tribe of Nevada & California, at the Tahoe Forest Products sawmill opening Dec. 18, 2023, “Our people have intervened in these areas since the beginning of time, because otherwise, if we don’t take care of it, it will take care of itself.”

********

There is a mutually beneficial relationship here – land management agencies need to treat landscapes and the timber industry needs timber. There used to be an old saying of “trees paying their way out of the woods.” That meant the value of the timber would help offset the cost of treating an area. While that’s not the reality on the eastern side of the Sierras, having a mill infrastructure in proximity drastically improves the economics of the type of work that’s needed to restore landscapes in the West.

When timber business makes assessments about when and where to take on a contract, they look at a number of factors — fuel and labor costs, and market prices for timber. But there is one factor that tends to be the most prohibitive — distance.

The further a log has to travel to arrive at the nearest mill increases fuel and labor costs and decreases a business’s profit. Depending on all the variables, the breakeven distance is about 50-80 miles from forest to mill.

Before the opening of Tahoe Forest Products mill in Carson City, the closest mill was in Quincy, California. That’s more than 100 miles from many of the areas that need work on the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest.

“Since the mill has opened the conversation has definitely changed,” said Monti, “Now contractors are calling and saying, ‘hey, I heard this new mill went in. I’m really interested in doing work on this side of the mountain.’… We have not had that option for the last several decades.”

Note the transportation costs, and the shimmering of the beginning of a new working-wood-wide-web. I always wonder why California seems to be different from Oregon in its appreciation of the Web- maybe the Timber Wars are still resonating.

*************