Before we dig into the timber details I talked about last week, and some examples of what I like to call “Post Timber War Convergence” (like my agreeing with Andy Kerr on something), I’d like take a look at the situation from the 30,000 foot level (as my former boss, Richard Stem, would say).

There have been many stories in the past few weeks about mills closing in Montana. Here’s an excellent one, thanks to a TSW reader.

Within the span of six days, both Pyramid Mountain Lumber in Seeley Lake and Roseburg Forest Products’ Missoula particleboard plant had announced they were shutting down permanently and eliminating a combined 250 jobs. The closures mark the final knockout punch locally to an industry that helped build Missoula and put food on tables here for over 150 years.

To put it another way: Sawmills were once as ubiquitous in Missoula as marijuana dispensaries are now.

There are smaller businesses in the area that still make wood products, there are still lumber mills operating in Montana, logging will still continue in the region and Pyramid Mountain Lumber’s facility could still be purchased and operated again in the future. But to many industry watchers, last week’s news was the final nail in the wooden coffin of the sector that’s paid the wages of tens of thousands of workers over the last century and a half.

“I mean, it’s huge, what’s happened to the wood products industry in Montana in the last five years,” said Zach Bashoor, the chair of the Missoula Area Chamber of Commerce, when asked how big of a deal last week’s news was. “Pyramid was the last sawmill in Missoula County and Roseburg was the last wood products manufacturing facility here.”

Bashoor has actually worked for both Roseburg and Pyramid in the past.“When a mill closes there’s a whole contractor base built around those mills that’s going to be affected, too,” he explained. “There’s a contractor out of Seeley that told me he thinks he’s going to hang up his hat.”

By contractors, Bashoor is referring to loggers who have a contract to sell logs to Pyramid. Oftentimes, they’re doing forest thinning for wildfire risk management or forest ecology restoration projects that require thinning. “They make a living out of selling timber to the mill, that’s how the system was built,” he said. “The demand of land management has changed to much more of a restoration aspect.” Bashoor owns a company called Montana Forest Consultants that services landowners and agencies doing forest management work.

“Without those (loggers), there’s no way to get our work done,” he said. “If they’re not around we can’t do things like watershed restoration projects or thinning small trees for hazardous fuels

reduction.”

In places in the West, say with Blue Mountains Forest Partners, or the Yosemite Stanislaus Solutions folks, sawmills and their downstream ilk are thought to be useful partners. In my own neck of the woods, an entirely private fuelbreak project is being supported by landowner donations, state grants and .. selling logs.

Without forest products industry around, we can expect fewer fuel projects to be done on federal land, they will cost more to the taxpayer, and less private mitigation is likely to be done. That’s just the cost element. What else will be done with the material removed? Will it be burned in piles, giving off smoke and carbon? And perhaps the old “fuel treatments and creating openings for species diversity are just an excuse for logging” argument will be at rest (as it currently is in places without mills). How would that change the litigation environment?

Meanwhile, the Congress/USDA/Biden Admin (wherever bucks come from) is giving out funding to help:

Today, the Biden-Harris Administration announced the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service is making nearly $50 million in grant funding available for proposals that support crucial links between resilient, healthy forests, strong rural economies and jobs in the forestry sector. Made possible by President Biden’s Investing in America agenda, a key pillar of Bidenomics, this funding will spark innovation, create new markets for wood products and renewable wood energy, expand processing capacity, and help tackle the climate crisis.

“A strong forest products economy contributes to healthier forests, vibrant communities and jobs in rural areas,” said Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. “Thanks to President Biden’s Investing in America agenda, we are investing in rural economies by growing markets for forest products through sustainable forest management while reducing wildfire risk, fighting climate change, and accelerating economic development.”

This announcement is part of President Biden’s Investing in America agenda to generate economic opportunity and build a clean energy economy nationwide. The grants are made possible by President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, the largest climate investment in history and a core pillar of Bidenomics, as well as President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, an historic investment to rebuild America’s aging infrastructure.

The above paragraph may take the prize for number of mentions of President Biden per word.

The open funding opportunity comes through the Forest Service’s three key grant programs to support the forest products economy: Wood Innovations Grant, Community Wood Grant, and Wood Products Infrastructure Assistance Grant Programs. The agency is seeking proposals that support innovative uses of wood in the construction of low carbon buildings, as a renewable energy source, and in manufacturing and processing products. These programs also provide direct support to expand and retrofit wood energy systems and wood products manufacturing facilities nationwide.

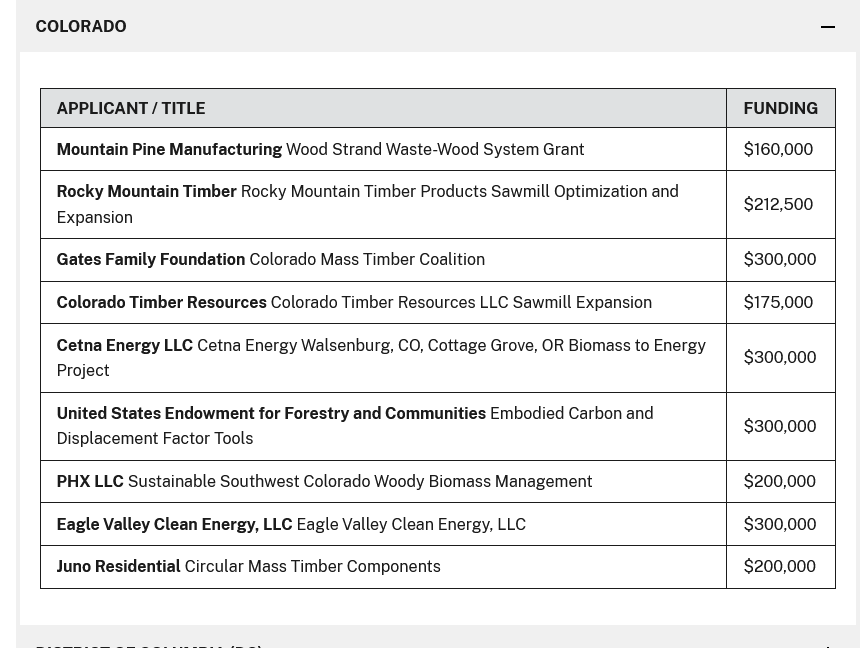

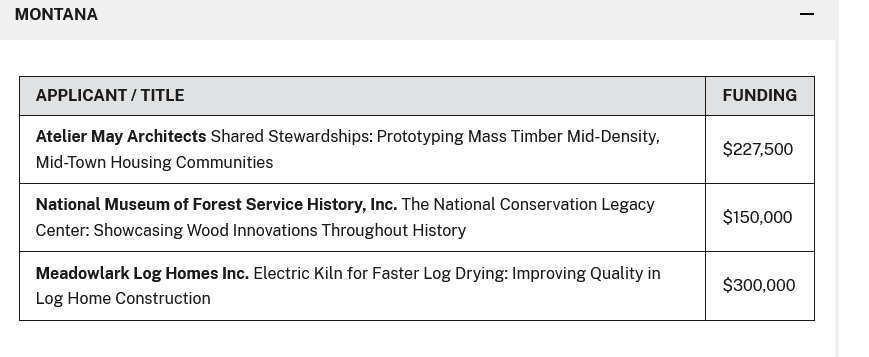

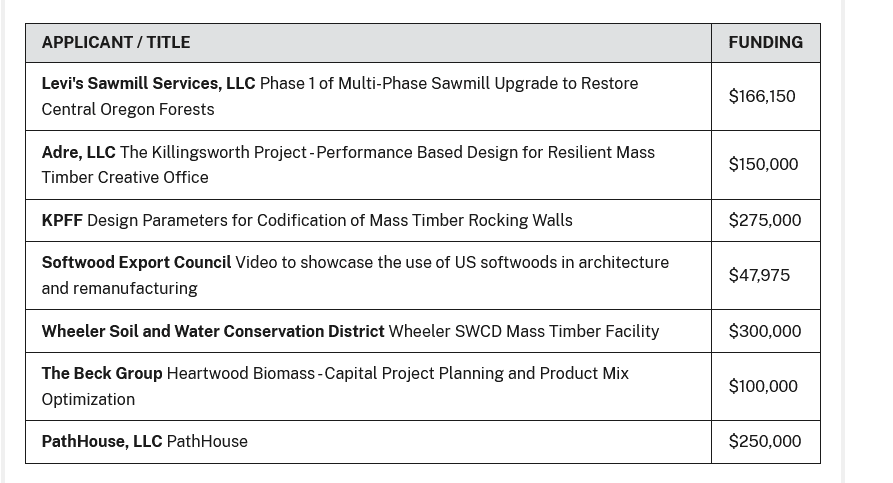

(Note that 2023 funded proposals are listed here.

Let’s compare Colorado, Montana, and Oregon.

I just looked at these three states and noticed grants to the Endowment and the Gates Family Foundation in Colorado. It seems like the USG is giving grants to.. traditionally grant-making groups. I also wonder if there is a bias toward “starting new things” vs. “helping keep existing things going” perhaps something like a “forest products facility rescue” as in reality TV.

Maybe our economist friends can help me here, if there isn’t a way for the USG to help keep sawmills open rather than letting them close and starting over with something new in the future. I think of nurseries.. we wanted them, we got really good at them (and reforestation), then we assumed natural regen would take care of everything, so we lost the capacity and the know-how and basically have to start over, now that the people have retired and the infrastructure has been sold off. Resilience, it seems to me, requires some redundancy and keeping skills and some infrastructure on board. Though that’s not actually redundancy in the engineering sense. Maybe it’s more like making sure that useful skills. knowledge and workforce are maintained at some level.

I am not familiar with Montana’s sawmills and timber industry, but in the places I am familiar with these things, I have noticed the trend over the past 30 years was that mill closures started with the smaller mills, and some of this was clearly done using monopolistic tactics. SPI was/is ruthless, and is a prime example of such a monopoly that systematically cornered the marked in the Sierra. Closing the smaller mills drastically increases haul distance. Long haul distances make it cost-prohibitive to focus on a smaller diameter wood supply. Closing poorly located mills may not be the worst thing. Sometimes starting over makes more sense than shoveling more money into a location that is no longer viable. I am personally in favor of providing public funding to support community-based sustainable wood-use centers, facilities that would rely on mostly smaller diameter wood and use all parts of the material to produce everything from lumber to biomass power.

Wouldn’t you also need to know how many Wood Innovation Grant applications (and might want to include Community Wood Energy as well – a sister program) were received from folks in Colorado and Montana as well? For all we know there were 3 applications from Montana and 100 from Colorado (I doubt it, but we just don’t know).

As someone who has helped companies with such grant applications and has reviewed grants for the USFS (different years, obviously) I can tell you that there are some very good applications, and some that, to be polite, have a lot of room for improvement.

Thanks, Eric! Sure I would like that info, but it doesn’t seem to be available easily. I didn’t mean to demean either state, I just thought it was interesting. And I think all these grant programs are worthy of attention. Maybe you would be interested in writing a post on “top ten things not to do in a grant application”?

Sure – maybe closer to when these grants are announced, so that it is actually useful to folks and not long-forgotten. The grant application announcement usually occurs during Forest Products Week, generally the third week in October. I assume you have my email – feel free to reach out in September and I will get something together for you.

Great, thanks! I’ll put it on my calendar.